An Interview With Alex Ross - Martian Manhunter and Other Influences

/Written by Bryan Stroud

Alex Ross, 2014.

TV Guide, Dec.8-14, 2001, cover by Alex Ross.

Nelson Alexander Ross (born January 22, 1970) is an American comic book writer and artist known primarily for his painted interiors, covers, and design work. He first came to prominence with the 1994 miniseries Marvels, on which he collaborated with writer Kurt Busiek for Marvel Comics. He has since done a variety of projects for both Marvel and DC, such as the 1996 miniseries Kingdom Come - which Ross co-wrote. Since then he has done covers and character designs for Busiek's series Astro City, and various projects for Dynamite Entertainment.

His feature film work includes concept and narrative art for Spider-Man and Spider-Man 2, and DVD packaging art for the M. Night Shyamalan film Unbreakable. He has done covers for TV Guide, promotional artwork for the Academy Awards, posters and packaging design for video games, and his renditions of superheroes have been merchandised as action figures.

Ross' style has been said to exhibit "a Norman Rockwell-meets-George Pérez vibe", and has been praised for its realistic, human depictions of classic comic book characters. Because of the time it takes Alex to produce his art, he primarily serves as a plotter and/or cover artist. Comics Buyer's Guide Senior Editor Maggie Thompson, commenting on that publication's retirement of the Favorite Painter award from their CBG Fan Awards due to Ross' domination of that category, stated in 2010, "Alex Ross may simply be the field's Favorite Painter, period. That's despite the fact that many outstanding painters are at work in today's comic books."

In case I'd not mentioned it before, the catalyst for my renewed interest in comics several years ago was due to a gift from my life-long best friend. He sent me a copy of Mark Waid and Alex Ross' Kingdom Come and the fire was reignited in a big way. I'd never seen the like of Alex Ross' work and was absolutely mesmerized with the story. It started me on this journey and there's been no looking back for over a decade now and I have often marveled at my good fortune. Well, a few years ago I was given a fabulous opportunity to interview THE Alex Ross! How could I possibly pass that up? The problem, of course, was what on Earth to talk about that he hadn't discussed in detail many times over? I thought and I thought and I came up with the fact that it was the 60th anniversary of the Martian Manhunter, a character Alex had portrayed masterfully in his oversized JLA book. I had an absolute ball speaking with the master painter and got to tell him just what his work meant to me and...well, you'll get to read his response. From the latter part of 2014, Mr. Alex Ross!

The Justice League of America by Alex Ross.

Bryan Stroud: Some factions believe that the debut of the Martian Manhunter was actually the first new hero of the Silver Age, while others maintain that it’s the Flash in Showcase #4. Then again, is the first character of the Silver Age a superhero or a science fiction figure?

Alex Ross: He would be both, realistically. He’s a character that distinctly belongs to the Silver Age, and he’s definitely a superhero, even if his costume looks like a leftover remnant of the S-F/pulp construct costume. But he…I know when you first read those original stories it doesn’t really read like a superhero story. It reads more like science fiction, but there’s definitely the superhero aesthetic.

JLA: Liberty and Justice (2003) 1 pg66, art by Alex Ross.

Stroud: Precisely, not to mention that he started out being a gumshoe, hence his placement into Detective Comics.

Ross: In a way I have a special connection to him because it was a unique thing in my own collaboration. I kept him largely out of Kingdom Come because initially the story needed to come down to this final showdown between Superman and Captain Marvel. Those two counterpoints. If you add in more power on the Superman side of the equation, in the form of the Martian Manhunter, in that final conflict, it’s not really going to work. So Mark Waid and I had sort of a disagreement about it initially and I had to sort of talk him into it - that he was being used by Batman and his team, but not in the sense of what you thought of for him.

He could still read minds and provide intel to Batman, but he wasn’t really up to being the superhero he’d been all this time. He’d been more affected by his time with humankind. That was a diversion from Mark’s ambition for the character to use him more ambitiously as part of a true unification of a classic Justice League hanging out with Superman in the Kingdom Come series.

My thought was that if you add him with Superman it’s almost like you’ve got two heads of the team and I always saw him as much more associated with Batman, especially because of the length of his tenure with the group. All of this sort of prompted me for when I got around to doing the one shot for Justice League and that I’d make it all from his point of view as the preeminent sort of narrator/character for the story. Because I had skipped using him.

He’s a character I’ve loved, but I just didn’t want to throw off Kingdom Come for all that it had been conceived to be. Plus what Mark didn’t appreciate or maybe see the same way as I was that in many ways Kingdom Come was itself an analog of the entire DC history rather than an approximation of the DC Silver Age that he was most fond of because when Superman defines his sort of Justice League kind of team, it truly was a snapshot of the Justice Society. As per the comics of the 70s and 80s where you’ve got Power Girl in there and the version of the Flash and Green Lantern are clearly much more the originals than the Silver Age versions. So throwing in Martian Manhunter is not really what I’m doing here. It’s not what I wanted to do.

Superman: Peace On Earth (1999) 1 Alex Ross

Many people have called out Kingdom Come as being a tribute to the old Earth 2 Superman up against older versions of DC characters in many cases. That was the thing I was trying to pay tribute to.

I didn’t really have a visual in mind, particularly as a shape shifter. He wouldn’t be older. So you wanted to have some sort of visual. His was more of an intellectual and had been damaged by his experiences. Sort of like David Bowie in “The Man Who Fell to Earth.” He’s still connected to his inherently alien roots and it left him as a compromised figure.

Stroud: Differences between Superman and J’onn. Physicality? Did that cause one to take off and the other to be somewhat sidelined?

Ross: One thing about John Jones is that he doesn’t have the iconography of a symbol that everyone can grab onto. He doesn’t have a complicated, romantic subplot in his background. His time in Detective didn’t involve any real romance. So these human connections that we make and the iconographic connections are missing. Maybe if he had some sort of stylized “M” on his belt or something, but because he’s a mostly nude figure running around, it sort of throws off what people use to identify him with.

While he’s absolutely essential to the group dynamic of the JLA, perhaps more so than Superman and Batman, because he was in the first adventure while they were not. It began with 5 characters rather than 7.

Intellectually he kind of inherited the role of the Spectre from the old JSA when they revitalized the whole Justice League concept.

I always for some reason, even as a kid, held this connection to the character and maybe it was just prescience on my part that one day I, too, would be bald.

Marvels (1994) #3, cover by Alex Ross.

There are a handful of characters that have this kind of look, so I had a passion for them. So, you’ve got Martian Manhunter, you’ve got The Vision, you’ve got the Red Tornado. They’re all this certain type as a sort of detached bald guy. I don’t know why.

Stroud: Detached is probably the ideal descriptor, too, He’s kind of Spock-like.

Ross: You mention Spock and there’s such an appeal for that. The world understands, because the world is in love with Leonard Nimoy. When you have these characters, and the impact they have in the world of comic book stories, they become the most interesting, sometimes main character in those books. Because they become unique as fundamental parts of teams. They’re the character holding down the book. The guy who’s just always there. They’re often the character that the writer of the book can make the most hay with. In writing the story they can extrapolate and built that character and develop it, whether it’s the Vision getting married, or the Red Tornado’s ultimate human development.

In the storylines the authors were building these team books and no one was competing with those main heroes or those who couldn’t do the same kinds of things as Superman or Batman.

Stroud: Whose idea was it to use him as the narrator?

Ross: The genesis of the oversize books was something I was building up to doing from coming off of Kingdom Come. I’d made a short detour to a Vertigo series for a year, but knowing I had this burning desire to return to Superman above all, I put together this pitch that was based around what I felt were the four icons of DC that I wanted to do the one-shots of and that were approved. Superman, Batman, Captain Marvel and Wonder Woman.

Beyond that there was nothing on the schedule or nothing predicted or nothing expected (by myself included) so when I got to the end of going through the Wonder Woman book, I knew I had this burning desire in me - this thought that I would rebel against this typical version of DC which is always mired in specific versions of their lead heroes. I thought, “Could I actually take this further by doing a full-on, Silver Age Justice League?” Which in my mind would be the most eternal version of the group because if you check back in a few years later, they’re going to most resemble the original version of the group. What they might have been if given time.

Batman: War On Crime (1999) #1, cover by Alex Ross.

You had the heir apparent to the Flash character, you had the guy who would be Green Lantern, you had Aquaman, who was still Arthur, but he was the most tripped-out, revisionist version of the character. He was unrecognizable to most people.

So not wanting to really play with those versions because they don’t inspire me, I wanted to rejuvenate through this little corner of DC that I was carving out. And part of the carving out that I was doing here related to illustrations I did for both the Warner Studio Store and the version of Justice League I did or even the covers I did for Wizard Magazine. I was bringing in the classic versions of these teams.

On the one hand, I felt like I was getting away with something. I was working against the editorial tide. Even though I may look like the most obvious company guy by the way I was embracing this company’s characters, I was actually being something of a rebel against editorial dictates. *chuckle* And that’s only continued.

I had done many illustrations that he was part of (John Jones, that is) and the idea of eventually building this one shot based around the Justice League, which, at the time... Remember that Barry Allen was still dead, Hal Jordan was still dead, Aquaman was still missing a hand. All these things were different with these main characters. But Paul Levitz had no editorial revisions that he had in mind. Everybody just sort of thought, “You’re off doing that crazy thing over there that nobody cares about.”

The truth was, at least at the point that I was doing the project, there was a feeling that I could get as much attention as anything else that was being published. And maybe that was true of other things that I just didn’t realize, but there was a sense that the audience was open to special projects and whether or not you had a story that was worth telling. Whereas it appeared after a certain point after the story was out that the audience was more properly trained to shy away from caring about special projects. They were more likely to concentrate on how the top talent in the business were only producing work that was more the mainstream from what was showing where the characters were now.

Marvels (1994) #0, cover by Alex Ross.

In some cases that was almost weirdly disconnected as far as having something like the Ultimate’s line from Marvel and their eccentric indulgence beyond normal continuity, but because it was fully embraced by the company and was of course conceived by one of the publishers, it had all the company support that other stuff, whether it was my tabloid books or other things like it, it did not come from the publisher or the company and they had no vested interest in it, so it couldn’t get the same kind of push upon the market or the audience.

So for the period of time I worked on those tabloid books it felt like I could get as much attention for these things as I could achieve. The hope was that you could check in on these things years from now and they would still be readable in whatever context.

Stroud: Why the original Martian design rather than the more humanized version?

Ross: Well, realistically, what I was exposed to in the late 70s, around ’76 and ’77, at that point, when he was being brought back into storytelling the artist that was working with him, I think it was Mike Nasser, who did a backup in Adventure Comics where he had a fight with Supergirl and that was probably my first impression with the character. He had the prominent brow and looked very interesting and unique.

Now, as to whose idea was the stupid thing. It was basically…and it will look like I’m grabbing glory for myself in some ways here, when the pitch was made to DC, I was actually wanting to pitch it myself. Mike Carlin was not exactly encouraging. He was editorial overseer of pretty much everything at that point. I didn’t have any of that kind of writer credibility yet. They would have had me go through a series of hoops to prove I could actually write something. And they may still be doing that with lots of people, but my Hail Mary was to reach out to my recently made friend, Paul Dini and say, “Hey, what do you think of this?” And he jumped on board and what that meant was that largely they would build from the concept, especially from the Superman story, the concept that I had an outline for early in the story and then he expanded upon it with a much more elaborate outline.

JLA: Secret Origins (2002) #1, cover by Alex Ross.

The way that we worked on the four books was that Paul would write a lengthy outline. He wouldn’t break down the pages or write out any dialogue. I would break down the full story in…it was very Marvel style. I’d never worked Marvel style, where I would lay out the whole thing and then his text would be provided after the layouts had arrived. So he could see where everything was going to go. That was the four books. Then with the one shot which was Secret Origins which we sold the Justice League for, and then the sixth book was the Justice League one shot.

That was one where I got it in my head the idea which I had to defend over the years. In a way the book itself was my 9-11. My reaction, because I wanted to build a story out of the issue of hysteria. I basically wanted to have the Justice League facing off against a hysterical public, and that was based upon what seemed to be an oncoming, arriving disaster of biological proportions.

Of course my biggest inspiration in the story, and it’s pretty clear when you look at it, is The Andromeda Strain. Because when I was a kid and I saw that movie, I thought it was the most realistic way you could ever do aliens, because you’re going to find that there’s microscopic life in the universe. The idea of toxic stuff was interesting for whatever reason, but think of how realistic that movie plays. Now that’s not quite so sexy placing it against a superhero group who punches things, but I had my reasons. It was a story that I grew up with and ---- most stories drawn by Dick Dillin. One was the two-part storyline in Justice League that was called “Takeover of the Earth Masters” and it’s from issues #118 and #119. It had the Justice League fighting a larger kind of biological threat. It looks like giant single-celled organisms that fall from the sky. They attack and sap the strength of the Justice League members, much like we had in the story.

But also there was a World’s Finest issue that had the Atom going inside of a human body and he was fighting some kind of malignant force that was in the story. Inside this body that Atom was trying to save. Basically I adapted both things in this one graphic novel. He does the whole Neal Adams Batman thing going inside of Flash’s body. Then there was the rest of the whole biological phenomenon in Africa. It was basically taking the two inspirations that go from that story to Dick Dillin’s Justice League story. It has its relevance also to me in that it was the very first Justice League comic book that I ever got. I was 6 years old and I think this was 1976.

Wonder Woman: Spirit Of Truth (2001) #1, cover by Alex Ross.

So it was so important to me that I was plotting this extensive storyline so that I could literally block out the entire story, wrote an extensive outline that covered all the points of the whole thing and handed it off to Paul for him to essentially compose the final dialogue. So this was much more…

I didn’t write it out the typical way where Paul would write it first. I basically handed him the story and Paul would, as I would hear about it later, would openly complain to our circles of people like Bruce Timm and Chip Kidd and our editor - basically kvetch about how his story had germs that the Justice League gets to fight and other stuff that I’d worked on like the short stories with Chip Kidd with Superman and Batman fight cool stuff, where people fought against things bigger than germs.

Now again I point this out because Paul never said any of that stuff to me while we were working on it. It’s not like I even got a fair shot to defend or even accommodate. It was just simply one of those things. Several people I talked to over the years asked why I formatted it toward that direction rather than something like the Superman/Spider-Man crossover or the Superman/Muhammad Ali book. Of all the things that were simply the greatest influences of my life, the major feeling I had was, you know I don’t need to create more fights where there’s a marketplace flush with material that contains that.

I just wanted to create something that felt sort of like it was something that would appeal to a kid as well as to an adult. I wanted to create this hybrid art form. Almost a children’s storybook where the hero can still be consumed by a kid.

It never really seemed to take off in any great way like say Mark Waid and Bryan Hitch did one oversized story of the Justice League that had more of that kind of level of action in it. Unfortunately that must not have performed as well as what would have opened up a whole market of people doing it. I’d have liked to have seen that. I mean it just didn’t have anybody’s real support.

I remember when I had to sit down with the art director Gil Posner with a pitch and he said it had to be better than Dick Grayson stops being Robin. That was my pitch! There was a whole lot more to it, but… He didn’t know what I was going to be pitching other than, “I have an Elseworlds idea.”

Shazam: Power of Hope (2000) #1, cover by Alex Ross.

Stroud: I guess you didn’t read a lot of the old Silver Age JLA stories.

Ross: I have all that stuff, but my major exposure to that had to be simply the tabloids released in the 70s which had those stories in it and I find the charm in it that certainly leaves a deep impression on my mind because I love the origins of things. But of course being much more a child of the 70s it was more Dick Dillin’s run and George Perez’s run and the Super Friends. A lot of what I was doing was a hybrid of all these things. The common ground. When you showed Martian Manhunter it showed appreciation for the Silver Age beginnings because he was there for the first many issues and then when he leaves it’s more of the 70s era. Because he’s ultimately replaced.

Then there’s the impressions of the world made from the cartoon, Super Friends. That’s where the group is led by a very active Superman and Batman, Aquaman and Wonder Woman. I can easily brush off Robin. But even when they expanded it later and added other members to the Justice League they left out the Martian Manhunter. So in my mind he was just removed from the general public so they couldn’t fully appreciate and understand and in part some confusion about his definition and that there is so much more overlapping with what you already have in Superman. That’s why of course you wouldn’t necessarily put him into the cartoon. The main reason they had Aquaman in the show was that he was somebody who did something fundamentally different than the other guys.

They could have included Flash, but essentially it’s one of the powers that Superman has. That was kind of my mindset. I wanted to bring all these guys together under the same roof. A lot of the illustrations I did for the Justice League. The Martian Manhunter was someone I almost discounted until I fully realized how important he was to the formative unit of the Justice League.

He never had heat vision did he? I get upset when I see them portray him with that and it’s, “When did he get that?” It would seem like if fire is a problem for him, he wouldn’t want heat vision. (Mutual laughter)

Marvels (1994) #2, cover by Alex Ross.

Bruce Timm will tell you that he’d rather work with Marvel characters, but this is what he was given, so he’ll work with the Justice League, but I think he was trying to put Marvel powers into the mix a little bit. It becomes very convoluted because the people that were taking charge of the stories weren’t actually the editorial overseer, but the talent. “Whatever you want. You’re in charge.”

While I always felt like whatever I was doing with the character, at least I could be consistent with what I understood. If you look at any of the stuff I did, not counting Kingdom Come, but the Justice League one shot and the Justice series that I did, you will never see Wonder Woman flying. Because in my world she should never have done the exact same thing as Superman. There shouldn’t be that overlap in power and by the same token, Martian Manhunter would never have heat vision.

Stroud: That would go far in explaining how you focused more on the telepathic abilities and the shape shifting.

Ross: Right and during the Grant Morrison run they were really exploring those sorts of things, whereas the guys in the 60s didn’t understand all the ramifications of what he could do. In the 70s when he was no longer part of the Justice League and then in the tumult of the 80s there was much more effort put into the capabilities of the character. You could get more of an idea of how different and alien he could be.

Stroud: Do you think that the fact that he didn’t have a stand-out foe diminished his potential?

Ross: That’s correct, other than a whole planet of white Martians, but there was never much done with that. That was something that was only teased out in the 70s and then they would build upon that in the 80s and then in the 90s it seemed like such a pivotal part of his past.

JLA: Liberty and Justice (2003) #1, cover by Alex Ross.

What used to bother me was when people would take the character and be completely indifferent to what had happened in the past with him. I would even have to correct this with Paul Dini. He would write that he was a sole survivor. He’s not a sole survivor! When he came here from Mars it might have been a desolate planet, but there were other Martians. He wasn’t the only one, he was just trapped here. He was stranded in the first established adventures, and eventually he would get reunited with his fellow Martians and I certainly didn’t notice any kind of reboot that completely wiped out the Martian race.

Eduardo Barretto/Gerard Jones series. One of the best works ever done with the character.

That really grounds what I thought of the character more than anything else.

Stroud: (This is where I tell him how profoundly Kingdom Come affected me.)

Ross: It’s always really nice to hear, but when I’m told I’ve rekindled something for the art form that someone once loved I wonder if that should come with an apology from me. Basically I just helped you get back on the drugs you were on before. So much of this business and the fandom we bring to this art form is a corruptive one because it starts overtaking your attention, your passion. If you’re a collector like I am, suddenly you’re getting stuff that you wouldn’t have…

It also dovetails nicely if you’ve read Darwyn Cooke’s “New Frontier.” For the stuff where he used Manhunter in that, it feels very much like a kindred project, because the story is entirely set in the 50s and so what he’s dealing with, with his own way of living in this society is very true to the roots of the character.

The goofiest thing that has built throughout my career is that I’ve made models out of friends of mine. I’ve got a particular friend I base my version of Superman on and so forth and so forth and I would usually be the guy behind the camera. In unique points, idiosyncratic points, I would put my face more in the character. So when you saw a couple of times in “Marvels” the Vision, well, that was me, being the Vision. So even in Kingdom Come when I had the character of the Martian Manhunter appear, by the time I did my one shot it was like, “Eh. Let me stand in for the Martian Manhunter.”

Kingdom Come TPB cover by Alex Ross.

Now after all these other books based on the likeness of friends of mine, I make this guy look a little bit like me. But that was more a functional thing of the fact that I didn’t have anything better who I could get to do the posing. The Martian Manhunter is just more of an expression with that down, kind of morose looking face and the exaggerated features that anybody can do to some degree. So, the ironic thing is that in a way this is the character who is ultimately me played on film.

JLA: Secret Origins (2002) Superman, written by Paul Dini with art by Alex Ross.

JLA: Secret Origins (2002) Martian Manhunter, written by Paul Dini with art by Alex Ross.

JLA: Secret Origins (2002) Batman, written by Paul Dini with art by Alex Ross.

JLA: Secret Origins (2002) Plastic Man, written by Paul Dini with art by Alex Ross.

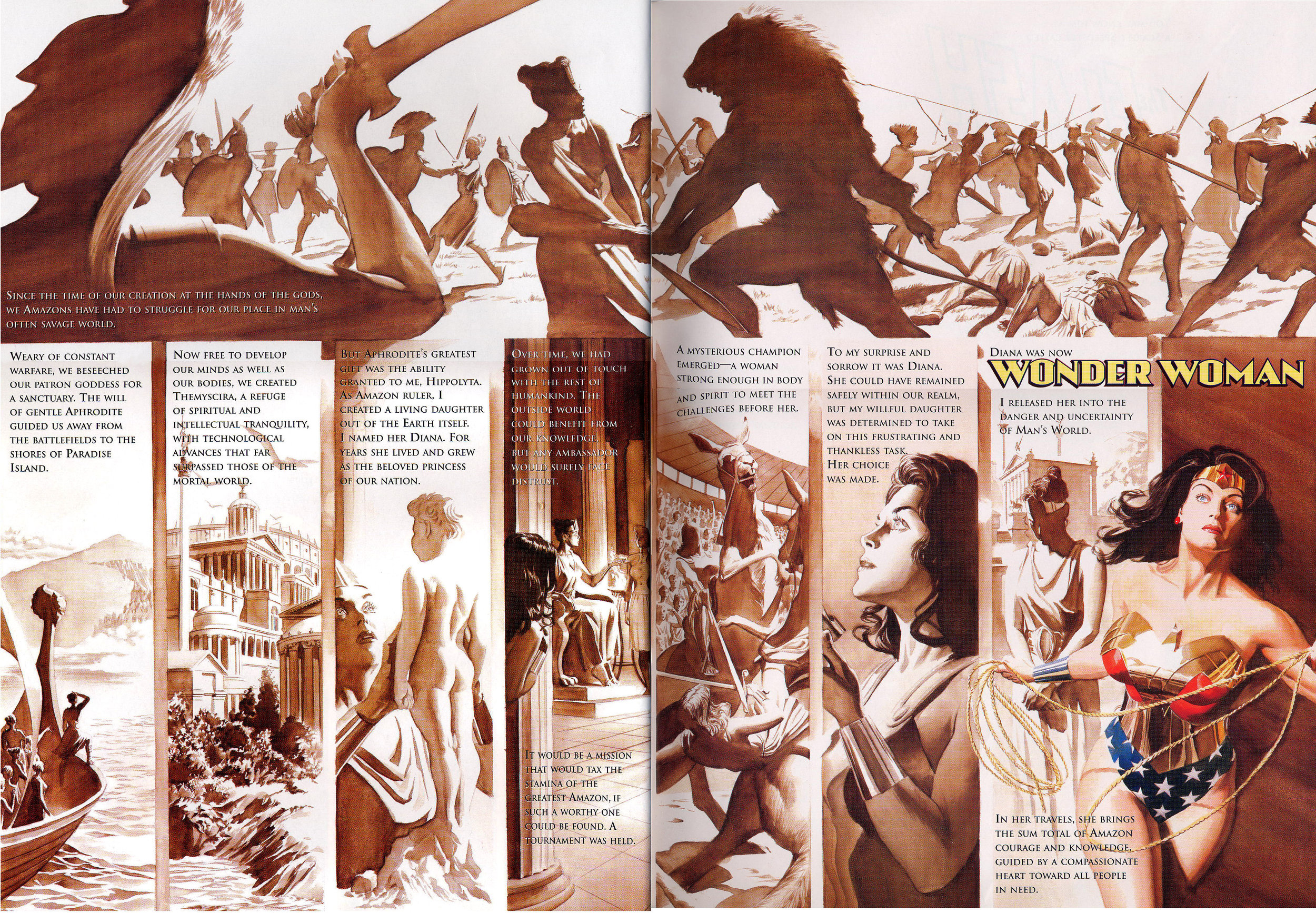

JLA: Secret Origins (2002) Wonder Woman, written by Paul Dini with art by Alex Ross.

JLA: Secret Origins (2002) Captain Marvel, written by Paul Dini with art by Alex Ross.

JLA: Secret Origins (2002) Green Lantern, written by Paul Dini with art by Alex Ross.

JLA: Secret Origins (2002) Aquaman, written by Paul Dini with art by Alex Ross.

JLA: Secret Origins (2002) Flash, written by Paul Dini with art by Alex Ross.