An Interview With Jim Shooter - A Lifetime Spent In Comics

/Written by Bryan Stroud

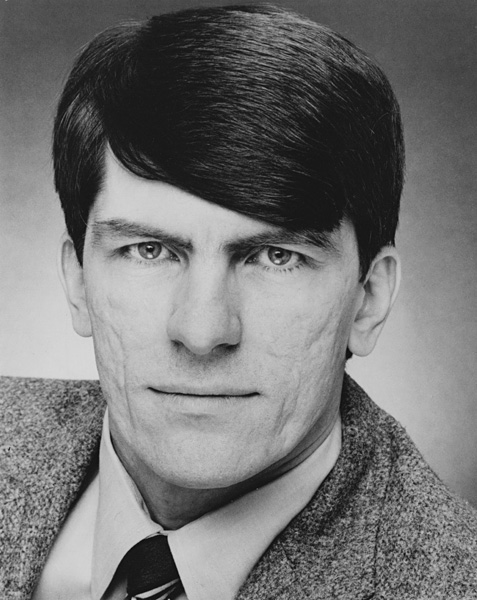

Jim Shooter

James Shooter (born September 27, 1951) is an American comic book writer, editor, publisher, and occasional artist. He started professionally in the medium at the age of 13 writing for DC Comics - though he is most widely known for his successful and controversial run as Marvel Comics' ninth editor-in-chief, and for his work as editor in chief of Valiant Comics.

This interview was one of my very favorites. Jim was so easy to talk to and has had such an unparalleled career in the comic book industry, from his early beginnings in his early teens, to climbing to the top of the heap at Marvel and founding other companies along the way. His stories were entertaining and informative, and he was as friendly and nice as you can imagine. Last year, my wife and I had the pleasure of taking him to dinner during his appearance at the Colorado Springs comic convention and it was as big a thrill as the initial interview we enjoyed.

This interview originally took place over the phone on March 8, 2008.

Bryan D. Stroud: You started at the record age of 13 in the industry, but I understand no one was really aware of it at the beginning. Was that by design?

Jim Shooter: Well, I lived in Pittsburgh, and the offices were in New York, so everything was done through the mail and I think, I have no way of knowing this for sure, but I think my boss, Mort Weisinger, the guy who hired me, I think he thought I must be a college student. I was clearly not an older man.

Young Jim Shooter.

Stroud: Sure.

JS: So, I think he assumed I was in college. What had happened was I sent in a story over the transom and he sent a letter saying, “Hey, this is good, send another one.” I sent him two more together in one batch. It was a two-part story. And then he called up and said, “I want to buy these and I want you to do more,” and he gave me my first assignment, and then after that every time I’d finish one he’d give me another one to do, and so I was like a regular after that.

So, I was working away and, after a couple of months, he called up and asked if I could take a couple of days and fly up to New York; the company would pay and everything and spend a couple of days in the office so I could get a little training. I’d been doing this all by just winging it. And I hesitated, because I’m a high school kid. I’m going, “Oh…uh…um…I don’t know.” And then he asked me, “How old are you?” And I said, “I just turned 14.” And he said, “Put your mother on the phone.”

Stroud: (Laughter.)

JS: So, what happened was that I did actually make the business trip, but I had to wait until school was over that year. It was my freshman year in high school. I had to take my mother with me on my first business trip. (Mutual laughter.) So that’s embarrassing, having to take your mother with you on your business trip.

Stroud: Oh, yeah, almost as bad as on a date.

JS: It was terrific, though. They flew us up to New York and we stayed in a nice hotel, he took us to a Broadway play. It’s a Bird, It’s a plane, It’s Superman, as a matter of fact. We spent a day at his house and I spent several days in the office getting things beaten into my head. It was a grand adventure with fancy dinners and all.

Stroud: Sure. It had to be quite the eye-opener at that point in your life.

JS: It was, yeah. He took great delight in telling me which spoon to use. (Chuckle.) So that was that story.

Stroud: I’ve read where you preferred reading Marvel comics as a kid and kind of wanted to incorporate more of their style into what National was doing. What exactly did you see at Marvel that DC lacked?

JS: Well, I was born in ’51 and when I was a little kid basically DC comics were, more or less, all there were as far as super heroes. I mean when I was a little kid I read Uncle Scrooge and Donald Duck and Superman and maybe World’s Finest. Whatever I could get my hands on. And when I got to be seven or eight it began to occur to me that it was the same story again and again and again. Comics in those days were written…at least DC comics, were written for young kids. Mort used to tell me, “Comics are read by 8-year olds.” Okay. So, I started to get bored with them. I quit. I stopped reading them, because I found them kind of tedious.

So, the years pass and I’m 12 years old and was in the hospital for minor surgery, and when you’re in a kid’s ward in a hospital in those days, it’s awash with comic books. (Chuckle.) I was in this room with 3 other kids and there are just stacks of comic books. So, I had to kill a lot of time and so I picked up some of these comics and the first ones I picked up were the ones that I knew; Superman. I read them and found that nothing had changed. (Chuckle.) It was like; there was no difference between 1958 and 1962. And one of the reasons I read the DC titles first was because the other comics were so dog-eared and ripped up and read to death. But finally, I got bored enough to try some of these newfangled Marvel comics and they were so much better. It was like, “Wow! These are fun!” So, at that time the idea flickered across my little 12-year old mind that if I could learn to write like this guy Lee, I could sell stories to these turkeys over here at DC, because they needed help. I mean I literally thought that; and my family, we were broke and needed money and when you’re 12 you can’t get a job in the steel mill, you know?

World's Finest Comics (1941) #172, main story written by Jim Shooter.

Stroud: Yeah, they frown on that.

JS: Yeah, so my only hope of making any money, besides delivering papers, was to make something and sell it. And I wasn’t qualified to weave baskets or anything, so I thought I’d try this. Everybody was just terribly amused by this whole notion, but I thought I knew what I was doing. I literally spent a year studying. I mean literally getting my hands on all the Marvel comics I could and trying to take them apart and figure out things like, “Well, usually by page 6 the bad guy shows up,” and stuff like that, and that’s when I wrote that first one and I sent it off to Mort Weisinger at DC comics. This was in the summer of ’65 when I was 13. I got back a nice letter saying, “Send us another one,” and that’s what started it all. The first one I wrote that was bought was in fact the two-parter I sent in after getting the letter. Mort later bought the first one I wrote.

Stroud: Fantastic and you were able to discern a little bit of…well, I don’t know if you could ever call Stan’s stuff formula, but the general gist and drift of how they worked.

JS: Yeah, the sense of it and the mechanics of it. I also realized that I was doing this to sell. I mean I think what most kids do is in their first issue they kill Aunt May and whoever their favorites are get married and they just do sweeping changes and stuff, and I realized that if I wanted to sell this, it’s got to fit in the pattern; so I was very canny about it. I tried to do a little bit of what Stan did. For instance, one thing I noticed was that Stan’s people talked better; they talked more humanly and that they had more personality. So I tried to do that. The thing is I really wasn’t a good enough writer at age 13, but since I didn’t know what a comic book script looked like, I actually drew every panel. Kind of a crude drawing. I didn’t try to do the finished art, it was just the only way I could think of to let them know what the picture should be. I think it was a combination of the visual thinking, like the script was okay and the visual ideas were good and I think that’s what kind of put me over the bar and made Mort think that they were good enough to buy and that I was good enough to train.

Stroud: So, it was almost like a thumbnail thing you were doing without knowing you were doing it.

JS: Yeah, I literally drew every panel in crude little drawings, just to show what was happening, and therefore was forced (chuckle), to do a lot of things right, like have the first speaker on the left and have enough room in the panel for the copy. I quickly discovered before anyone had ever told me that once you get up over 40 words you’re probably in trouble.

Stroud: (Laughter.)

JS: No, seriously. That’s a good rule of thumb for a regular sized comic book panel, and no one told me that, but when you’re lettering it all in (chuckle)…

Stroud: Yeah, it becomes very apparent.

JS: Its like, “Oh, geez, this copy takes up the whole panel.” So, what I ended up with was good enough to make the cut. And also, the timing was good, because comics went through a big decline in the 50’s and literally for years if DC needed a penciler or a writer or whatever, there were a lot of unemployed guys on the street. They would just call up one of the many people who’d been laid off, because all of these other comic book companies were going down the tubes.

Adventure Comics (1938) #368, written by Jim Shooter, cover by Neal Adams.

Well, eventually, they kind of ran out of them. People had moved on and done other things; they died, they retired and it had kind of come to the point where DC actually needed new people. So right around that time I turned up just when they needed somebody, and P.S. - a lot of other people turned up around that time, too, right around when I came in. There was also Archie Goodwin and Denny O’Neil and E. Nelson Bridwell, Roy Thomas. Shortly after me, I think, came Neal Adams. A whole new wave came in except that they were all like 30 or 40 (chuckle) and I was 13.

Stroud: Was this also right about the time when Arnold Drake and some of the other folks were trying to start up the guild or whatever? Did that have any impact on things or were you aware of that at all?

JS: I’d never even heard about it. I was in Pittsburgh. My only contact was Mort Weisinger. He kept it that way on purpose. And when I came up to the office, as I did periodically after that first trip; by the way, I only had to bring my mother once. These days if you let a 14-year-old kid go to New York on his own, from Pittsburgh, they’d come and arrest you. But in those days, nobody batted an eye. I mean, once I’d been up there and Mort had seen that I was a foot taller than he was, I would go on my own. Stay in a hotel. No one batted an eye and it was all fine.

In those days the policeman was your friend; any adult would take care of any child, so, anyway, I used to go up on my own sometimes and have these training sessions with Mort and various people. He taught me…I mean I was taught coloring, I was taught inking, I was taught…not so much penciling, but sort of penciling story-telling. How to convey the stuff dramatically and production and covers and also licensing and marketing, all kinds of stuff; I think he was secretly grooming me to someday be an editor. So, I met other people in the business, but it was always under Mort’s supervision. No way he’d let me hear about a guild.

Stroud: Yeah, and obviously that (YOU BECOMING AN EDITOR) did come to pass later. You created several new members of the Legion including Ferro Lad, the ill-fated Ferro Lad. Where did you draw your inspiration for those? Did they just spring forth from the brow of Zeus? (Chuckle.)

JS: You know what? In those days, yeah. I mean in those days I was young, enthusiastic and I’d just kind of do it. I didn’t even know how. I was really winging it and sometimes I would just…you know one of my problems with the Legion was that there were too many guys with powers where they’d point their fingers, I mean that’s it, whereas with Marvel comics people actually hit things, knocked things over and lifted things. So, I tried to come up with guys who were strong and powerful and knew karate and stuff like that. But other than that, with a lot of those early characters I just one day said, “Ferro Lad.” Hey, I lived in Pittsburgh. It’s a steel town.

Stroud: (Laughter.) Perfectly logical. Now at the time it was almost unheard of to kill off a hero. Was he slated to die from the very beginning? It was a fairly brief interlude from his introduction to his demise.

JS: Yeah, like four issues. Basically, yeah, I wanted to kill a hero. Remember I said I wanted to make everything fit in the pattern and I didn’t see a lot of heroes dying. Well, Lightning Lad died temporarily and they brought him back. So, I thought probably that wouldn’t fly if I wanted to kill one of the other characters, so I thought, “Well, if I make up one of my own, maybe they’ll let me kill him.” So, he was brought in as the victim right off the bat. I was actually still amazed that Mort went with it. He didn’t have a problem with it. Anyway, that was the plan.

Stroud: It’s kind of interesting because it seemed like he actually made more appearances post mortem than prior. He really wouldn’t die.

Adventure Comics (1938) #353, written by Jim Shooter.

JS: Yes and no. I like characters to stay dead if they’re dead and as you know, in comics, if you follow them at all, like Phoenix they all come back somehow.

Stroud: Right.

JS: Superman comes back…and you know I never really liked that idea. I acquiesced to it a couple of times at Marvel like when Frank Miller wanted to bring back Elektra. “Oh, geez…” And of course, when you have a character like Phoenix you expect her to come back, but in any case, he did remain dead. He just showed up as a ghost sometimes. As far as I know he stayed dead.

Stroud: Yeah, or as a long-lost twin or whatever.

JS: Well, I never paid any attention to that. (Chuckle.) I don’t count that. That was one of the things that I was thinking when I started out writing the Legion. “These guys go and get in all this danger all the time and no one ever gets hurt.” So I wanted to be more realistic. People might get hurt sometimes or somebody might die. And that’s why I did it. Anyway, that’s the Ferro Lad tale. By the way, he was supposed to be black.

Stroud: Oh, really?

JS: Yeah. That’s why he had a mask on. I noticed there were no black characters anywhere, except at Marvel with the Black Panther. What an unfortunate name. And a few others, maybe working a few black characters into a crowd scene. I thought why wouldn’t there be a black guy? But I suspected that would be a problem. So, I put the guy in a mask. Actually, the truth is, I drew him wearing a mask first, and I hadn’t really thought it all out, but being that he was conveniently in a mask, I thought, “Okay, he’s black.” He was in a mask in my first issue.

Then I mentioned the idea that he was black to Mort and he vetoed it. “No way.” “Why not?” He said “Because then all the distributors in the south won’t carry the book.” I thought, “Well, I don’t know how to argue with that.” Anyway, he adamantly refused. Meanwhile Marvel sort of bravely marched on and started having more and more black characters and stuff and they seemed to get away with it. (Chuckle.) By that time Ferro Lad was dead, so it didn’t make any difference.

Stroud: It sounds a lot like the story Neal Adams was telling me with the drug scene and so forth where Stan, as you said, just marched ahead with it and then all of a sudden, “Gee, they’re doing it. I guess maybe we could.” (Chuckle.)

JS: You know I don’t know whose came first, Stan’s or mine, but we actually did a drug story in the Legion. It was around the same time, and I certainly hadn’t read his when I did mine so I don’t know whose came first, but basically I did a backup story, this was when the Legion was moved into Action Comics, and did a backup story called “The Lotus Fruit,” where Timber Wolf gets addicted to this Lotus fruit, which is a hallucinogenic fruit and in the original ending he did not kill what’s her face, but he did remain addicted and had to go through like rehab and stuff like that and it was rejected by the Comics Code. So, for Mort it was the only story I ever had to do any re-write on. He said, “You’ve got to change the ending. It’s got to be that when his girl was in danger he just heroically somehow throws off this addiction and then he’s cured. Period. And drugs are bad.” So, I wrote it, the hokey ending. We caved in and Stan didn’t. (Mutual laughter.) So, there you go, the two companies in a nutshell for those days. It’s different now.

Stroud: Very much so. It’s kind of interesting that among your other creations the Fatal Five has had remarkable staying power. Did you have any inkling that they’d endure for 40 years? I’ve even seen them in animated cartoons.

JS: The story there is that back in the ancient days of the Legion, Mort used to tell Otto Binder or Edmond Hamilton or whoever, he’d say, “Knock off Moby Dick.” (Chuckle.) And then you’d get “The Moby Dick of Space.” And they would. They’d do the giant space whale against the Legionnaires. And they would literally do that. They would just pick a classic and kind of do the Legion version of that. It was a normal thing. So, I’m working away for Mort and one day he calls me up and he says, “There’s a movie coming out called ‘The Dirty Dozen;’ go see it and then do a story like that.” “Huh? What?” So, I was just appalled. I can’t go see a movie and then do it as a Legion story. So, what I did was I looked in the newspaper at the ad and that’s all you had to see. “Okay, it’s World War II. They get bad guys for this suicide mission that no one can accomplish.” All right. I can do that. I never saw the movie. And to this day I’ve never seen the movie.

Adventure Comics (1938) #352, written by Jim Shooter.

Stroud: (Laughter.)

JS: But I know that it was a World War II thing where they recruited nasty criminals to go on this suicide mission and so that was simple enough. I just worked it out. I thought first of all that it’s got to be a big enough threat that the Legionnaires need help. (Chuckle.) Second, there’s got to be a reason why the bad guys would do this. And then I cooked up the whole thing with the Fatal Five and the Suneater and all that crap and yeah, I am surprised that they have endured so long. As a matter of fact, I’m surprised sometimes when my little box of DC comics comes from Cable Corps once a month and I go through it and, “Hey! That’s one of my guys!” (Chuckle.) It’s kind of cool seeing all these characters pop up again after, what? It’s been 43 years for me.

Stroud: Exactly. My daughter giggles at me because I’ll watch JLU or something and I’ll suddenly gape at it and say, “Do you know who that is? That’s Mordru! Mordru the Merciless! Do you know how long he’s been around?” (Laughter.)

JS: Yeah. I remember Mordru.

Stroud: Another of your characters, as a matter of fact. Like I said the legs some of them have are pretty remarkable. It must be somewhat satisfying for you to continue to see that after all this time.

JS: Yeah it is, it’s nice. They make toys and stuff. It’s really cool. I have to say DC comics really have been good about stuff like that. Every time a toy comes out, a Legion toy of any kind, even if I didn’t create it, Paul Levitz sends me two copies of it. One for my kid (chuckle) and one for me. He used to always send me one and I wrote him a thank-you letter and said, “I give these to my son, Benjamin.” Well then, I get a whole second set. It’s Paul and, “Well, you need some for yourself.” And then on top of that in recent years, every year, once a year I get a check from DC. They don’t owe me anything. I mean all that stuff was work for hire. But they say, “Hey, your stuff is appearing in this cartoon show and we’re making these toys and stuff. We don’t owe you this, but here’s a token of our gratitude.”

Stroud: Very nice. You can’t beat that at all.

JS: No, I tell you, it’s been great. I thought, “Wow. That’s how I would do it if I were there. If I were running the show that’s what I would do.

Stroud: It’s only right. In fact, I think I saw on Neal’s webpage he was receiving a check from Paul for some such thing and he was touting what a stand-up thing that was to do and so forth.

JS: Yeah, it really has changed. (Chuckle.) Neal used to always say that the original building DC was in at 575 Lexington, it started out being this golden color. It had this sheet metal exterior, golden color and Neal used to say that as the years passed he watched that fade to sort of a shit brown.

Stroud: (Laughter.)

JS: It really did, (chuckle) but I think they’re back to gold now, as far as I’m concerned. They’re doing good. I mean, it’s a big company and things will go wrong, and they’ll irritate me once in a while, but basically, I think that they’ve done a lot of stand-up things and kind of feeling their way along with some stuff, but they’re really doing pretty well.

Stroud: Very good. Can’t ask much more. I saw on the Grand Comic Database that you were given credit for penciling a couple of the Adventure stories and that you did some layouts as well. Do you recall that?

JS: Well in my first stint with DC I did those little layouts for every single panel of every single page of every single story.

Action Comics (1938) #378, written by Jim Shooter, cover by Curt Swan.

Stroud: Okay, so that’s what they’re referring to.

JS: Yeah, I would do these roughs, but…I mean they were comprehensive. Everything was there. This cracks me up about Wikipedia and places like that is like on a story where I wrote it; I laid it all out; I drew the character and drew the costume he was in, to the best of my ability, obviously Curt Swan did the final art and it looked a hell of a lot better, but they’ll give credit to the penciler as the co-creator of that character. Why? They penciled the issue, yeah, but I drew that guy. Every detail about him is from me. I came up with it all by myself. Nobody coached me. Oh, the other thing that cracks me up is when they give Mort plot credit. I mean, “He couldn’t possibly have done this, so it must be Mort.” They’d give Mort plot credit on stuff I sent in over the transom. I mean, come on. Anyway, it’s not like it makes a big difference in my life. But it’s like I’m the “co-creator” of a character that I did everything on.

Stroud: Exactly. I had the opportunity recently - when it came to my attention that the original art for the Green Arrow postage stamp from a few years ago was up for sale on ComicLink....

JS: Yeah, I remember it.

Stroud: Anyway, the description was touting it as being by [Jack] Kirby, and it’s got Mike Royer’s name right on it and so I forwarded it to Mike and I asked if Jack penciled it and he wrote back and said, “No and by the way Roz Kirby did not approve it, either. Would you mind telling them for me?” “I’d be glad to, Mike.” So, I understand the mindset. Give credit where credit is due.

JS: I don’t begrudge any credit to Curt Swan or the other guys, because they did great stuff for me and had to put up with a lot of bad drawings. (Mutual laughter.)

Stroud: A couple of different people interpreted your stories. Did you appreciate one over another? Gil Kane or Curt or whoever?

JS: I’d have to put Wally Wood and Gil Kane at the top of the list. Curt, certainly. I think other guys would kind of take more liberties with it. Some of that…I don’t want to sound like I’m complaining too much, but sometimes I would call for a difficult shot. And if you’re a comic book artist and you’re getting paid by the page and there are no royalties and this crazy kid in Pittsburgh wants you to draw 25 Legionnaires and the city of Chicago and a hundred elephants, each with a different flag, yeah, you do a big head and (chuckle) you hope that he writes a caption that says, “Meanwhile…” Anyway, there were some guys who really honored the layouts, like Curt. I mean if I called for it, he drew it. He might change the angle a little bit or he might…he would improve it. No question. But he really did deliver what was asked for. And the same with Gil. I think Gil just threw the stuff on the light box and doctored it up.

I’ve got a good Gil Kane story. I’d never met him. He never was in the office when I was up there, and the first time I ever went to a convention…I didn’t know there were conventions, but the first time I went Gil Kane was being interviewed on stage. And at that point since I lived in Pittsburgh and had been kind of sheltered by Mort, pretty much nobody knew who I was; to look at, anyway. So, I went into this interview and the interviewer happened to be a guy from Pittsburgh, and he saw me. He kept interviewing Gil and then he started asking Gil, “Who are your favorite writers to work with?” And Gil said, “Writers are all idiots.” (Mutual laughter.) And the guy said, “There must be one that you like.” He said, “Well, there was this kid from Pittsburgh…” And the interviewer said, “Are you aware that he’s in the room?” He said, “No. I never met him.” So, they called me up and I met Gil Kane on stage for the first time, introduced as the only writer he ever liked to work with. The reason for that is not because I’m a great writer, but because I did all the layouts for him. (Laughter.) So, he could just zip through all that stuff. But it was really a fantastic thing. Good old Gil.

Stroud: Oh, yeah, it had to be just a bit surreal. That’s funny.

JS: And like I said therefore, just like Curt, he would improve it, but he would follow what I did, and so did Woody. Woody did one issue with me and up until then other than a mention here or there in a letter column I’d never gotten my name on a book because DC didn’t do credits. Now, of all the people at DC, there was only one guy who would sign his work and they wouldn’t white it out. If anybody else signed their work, they’d white it out, but Woody they didn’t mess with. I think it was probably because he had a .38 in a shoulder holster.

Superman (1939) #199, written by Jim Shooter.

Stroud: (Laughter.)

JS: Seriously. But he would always do that little Black Forest Script “Wood” somewhere on the first page. Woody, (chuckle) Woody and Gil had this in common; they both hated writers, except that Woody also hated editors and art directors.

Stroud: (Laughter.) Equal opportunity.

JS: Anyway, when Woody was given my script, which was all these layouts with all the lettering, he drew it and I’m sure he found it easier, just as Gil did. He honored it. He did it…well he made it look 100 times better, but he basically did what I asked him to do and on the first page of that book he put “Shooter and Wood.” I wasn’t a writer, he thought. “The kid’s an artist. He gets credit.” (Laughter.)

Stroud: Outstanding.

JS: So, years later when Woody was working for me I told him that and he said, “Well, I hate writers, but you’re an artist.” Funny stuff. And they didn’t white it out because it was Woody. Mort always used to say, “The character is the star. I don’t want anybody to know who YOU are, I want them to care about Superman.” “Okay, I don’t care, shit, just send the check, I don’t care.”

Stroud: Is there anyone over the years you wish you’d had the chance to work with but didn’t?

JS: Yeah. Lots of guys. There was just tremendous talent out there. I gave Frank Miller one of the first jobs and coached him a little in his early days at Marvel and I never got to work with him. It just didn’t come around. He was slow at first, so it wasn’t hard to keep him all booked up. (Chuckle.) It just never coincided that he was around to do something that I needed. He did some covers off of my sketches, but that’s about it. Lots of guys, I just can’t think of them all.

Stroud: Sure. This has been a few decades ago after all.

JS: By the way, it was great working with Neal, although I only worked with him on covers. In the old days with Mort, with every story Mort required a cover sketch or a detailed cover idea if the writer in question could not sketch. As a matter of fact, he required two cover sketches for each story. What he would do is he would take the better one and make it the cover and make the other one the splash page because he used to do the symbolic splashes, rather than splash panels that started the story. He’d call it the second cover. So, I did two cover sketches.

When I did the interior stuff I just did it in pencil, but with the cover sketch, I colored it, because they taught me how to color, so I did a whole color comp of this cover. I put the logo and everything. And usually they’d pick one of my designs and follow it. I can’t think of an instance where they didn’t pick one of them. What was really, really cool was the first time the book comes out and I see the cover and it was Neal Adams. It was like, “Whoa!” It was amazing. Because more than any other guy, Neal would look at my crude little drawing and he would know what I meant. And he would say, “All right. I’ve got it.” And then he would do this brilliant thing that was like he was reading my mind. (Chuckle.) And I would look at it and say, “Yeah, I meant that.” (Mutual laughter.) “That’s what I meant. Yeah, good work, man.”

Stroud: Just knocked it out of the park.

JS: Oh, unbelievable. Doing those covers with him…I just couldn’t wait to see what he did.

Stroud: Sure. You and the rest of the world. He’s a formidable talent.

JS: He’s doing a cover for the new series, by the way.

Stroud: Oh, is he? I hadn’t heard that.

JS: Yeah for issue #44. Yeah, he asked to do it. He actually sent an e-mail to Levitz and Didio saying, “Hey, good move hiring Shooter and I want to do a cover.” And they asked me, “Would that be okay with you?” I said, “Oh, sure, let’s give the kid a break.”

Stroud: (Laughter.) Yeah, I guess we could do that.

JS: “We could see our way clear.” So anyway, he insisted I give him a sketch, and so I did, and now I’m sitting here and can’t wait to see it. I can’t wait to see it. It’s going to be cool. I’m not going to get many covers from him, he’s a busy guy, but it’s a very, very cool that he wanted to do one.

Stroud: Absolutely. I can feel the chills down your spine from here.

JS: It’s going to be good.

Legion of Super-Heroes (2005) #38, written by Jim Shooter.

Legion of Super-Heroes (2005) #44, written by Jim Shooter.

Legion of Super-Heroes (2005) #44 Neal Adams Variant. Written by Jim Shooter.

Stroud: Was there any particular creation that you came up with that you liked above all others that really satisfied you?

JS: Hmmm. You’re talking old days. I was very happy with the Parasite. I think I did that when I was still in 9th grade. Yeah, I was. And it was one of the early Superman stories I did and the story was not great. I did not do a great job, but hey, come on, give me a break. I was 14. But the character idea I thought was good. They asked me to write a Superman story and I looked at the Superman villains lying around and thought, really, this guy hasn’t had a new villain forever. And the villains he had were all scientists or sneaky guys. They weren’t real heavyweights.

So, I wanted to have somebody who was a physical challenge for him. So, I was in 9th grade, and in Biology class we’re studying parasites and I said, “Hey!” (Chuckle.) And to this day that character is still around. You see him every once in awhile. He was on the cartoon show and that’s kind of cool. That’s one of those that just sort of leaped out and I’m happy with how it turned out. I tried to create a lot of interesting ones. I liked the Fatal Five and Mordru.

Stroud: Right and after all most of the time your hero is only as good as what he or they are pitted up against and so it’s an important part of the formula.

JS: Right. Absolutely. I look around comics these days and I’m not seeing enough of that. There are some guys who are coming up with new stuff with a fair amount of frequency, but an awful lot of guys are just sort of strip-mining everything that’s already there. We as an industry need to get back to dazzling people with our brilliant creativity.

Action Comics (1938) #340, main story written by Jim Shooter.

Stroud: Very much so. It seems like a lot of the creators I’ve had the privilege to speak to look at a lot of today’s stuff and they just shake their heads. It’s more form over substance if that.

JS: I agree. I think that a lot of this stuff is…I mean the art is so good. It’s better than it ever was, I think. The guys can really draw, which is not to say they’re telling the story well. The line is really good. Probably the best quality of draftsmanship we’ve ever seen, but the writing I think has gone down hill. Back in the 50’s and 60’s some of the stories might have been dull, but you could pick up any comic book by any publisher and you could read it and it would make sense. Nowadays you pick up two dozen comic books at random off the shelves at the local comic book shop and you’re lucky if you can find one that you can make any sense out of. I’m not even talking about if it’s any good. I’m talking about being able to actually follow it.

And you know something? If I have trouble, and I’ve been doing this for a long time, what if some new kid picked up one of these? I got my comp box of DC books the other day and in one written by a “star” writer, the characters are talking, and they’re referring to the “Halls.” The Halls doing this and that and I’m thinking, “Who the hell are the Halls?” Finally, I thought, “Isn’t that Hawkman’s last name? His civilian identity last name?” Yeah, that’s who they’re talking about. And if I didn’t have that dim memory in the back of my brain someplace, how would anybody else ever understand what these people are talking about? I used to do the brother-in-law test where I’d give my brother-in-law, he’s a smart man, he’s a lawyer, and I’d give him a comic book and I’d say, “Read this and tell me what you think.” He’s an avid reader. He would always have a novel he was in the middle of, and he would sit down and most of the time he’d get to about page 3 and just kind of throw up his shoulders. “I can’t make any sense out of this.” And if he ever got to the end of one, then I knew it was okay.

Stroud: It sounds like a perfect test, and you’re right. Without that back story…

JS: Introduce the characters.

Stroud: There’s a thought. (Laughter.)

JS: (Chuckle) Give us a fighting chance! You don’t have to tell us every detail of the guy’s existence, but “Oh, his name is such and such. I think he’s a good guy. Oh, I see, he flies. Okay, cool.” That kind of thing. It’s like I tell everybody, go to the local Barnes & Noble. Pick up any book. You can probably read it and make sense of it. Turn on the TV. Watch a show you’ve never seen before. You’ll figure it out. In the first couple of minutes you kind of find out who everybody is and what’s going on. Go to any movie, except Lost Highway, and you can pretty much follow it. You might like it, you might not, but you don’t feel like you’re in the middle of a Swedish movie with no subtitles. But comics? A lot of them you just have no idea what’s happening and you feel stupid, because it looks like you’re expected to know who the Hall’s are. And comic book guys are adamant about it. They will defend this stuff. They’ll say to me, “Oh, you want to make it tedious and boring.” No. Read a Stan Lee book. I never felt I was being lectured to or he was boring me by showing me that The Thing was strong, because he would do it in a way that was clever and interesting, a part of the story and you liked it. “Okay, that guy’s strong.” They don’t get it. You try to explain it to them and they think you’re a dinosaur.

Stroud: Yeah, and then wonder why the industry’s been struggling so badly the last many years.

JS: Well, I hope the Legion is better than that. I mean I hope this new Legion is readable. Francis Manapul is a great artist. He’s still young and he’s still learning. He’s going to be a good one.

Stroud: It sounds like it’s off to an excellent launch and there’s certainly been plenty of ink or electrons spilled about your return, so that bodes well also.

JS: I think that once Francis and I get to work together a little bit more and we’re all on the same page…well, I’ve already seen it. This guy gets better with every page. He’s a kid and he’s got tremendous talent, but there’s a lot of stuff no one has ever even told him, (chuckle) like explaining establishing shots and introducing characters, but I’m always dazzled when I see what he drew. He works so hard and there is so much work in every page. So, I think that’s gonna come around and I want to be there when he gets his Eisner.

Captain Action (1968) #1, written by Jim Shooter.

Stroud: When you did your short, very short work on Captain Action, did you continue to follow it after Gil [Kane] took it over?

JS: No, I didn’t really.

Stroud: I just wondered if you liked the way it went from there. Of course, it obviously didn’t last very much longer, but legend has it that a lot of that had to do with licensing problems or some such.

JS: Yeah. Well the thing was, when Mort called me up and said, “I want you to create a new character,” I said, “Great! Oh, my God that’s great!” And he said, “His name is Captain Action and he has Action Boy and the Action Puma and he’s got the Action Car and that Action Cave.” I thought, “Oh, there’s a lot left for me to create.”

Stroud: (Laughter.)

JS: And some kind of mythological powers and he does this and he does that. He said it was a toy and this is what you need to do. So, I said, “Oh, okay, so I’m creating something, but I’m really creating nothing.” So anyway, I did it the best I could with Action Boy and the Puma or panther or whatever it was. Anyway, it was okay, but the best thing about that was that Wally Wood drew it. Oh, my God. It looked great. It was limited, both by my lack of skill because I was still just a kid and also by all this stuff that was foisted upon me and then the second one; Gil Kane, inked by Wally Wood. Oh, my God. At least it looked great.

And then during those two issues everything was kind of dictated to me, but I think that after that for some reason they just gave it to Gil and no one cared any more. Like they had done what they needed to do in the first two issues to satisfy the client or the licensor and after that Gil got to do whatever he wanted to do and I guess he still had to use a toy character with Dr. Evil. He still had some constraints, but he basically had a much freer hand and I know that he did way different from what I did and I don’t blame him. But I didn’t really keep track because I had enough trouble trying to graduate high school and get a scholarship and support the family and just had too many things going on to keep track of anything other than what I had to keep track of.

Stroud: Sure. Everybody has a Mort Weisinger story and I’ve heard it speculated that even though his style was somewhat abrasive at times it was necessary to keep things rolling and people on deadline and so forth. What was your experience, if you don’t mind?

JS: Well, right up front, one of our first conversations, I think it was the conversation we had right after I told him I was 14; up until then basically our conversations consisted of, “Send me a Supergirl story, 12 pages.” And I would send him a Supergirl story, 12 pages. Then he’d say, “I need a Superman story. 22 pages.” And the conversations, that’s all they were. I was doing the stuff all on my own. We hadn’t really quite gotten into a thing where we were talking about plots or stuff.

And then he found out I was 14 and I remember he said to me, “Look, even though you’re 14 I’m going to treat you exactly the way I treat every other writer.” And I said, “Okay. That’s fine.” Well, I didn’t realize what that meant. I think that was also the point where he really decided that he wanted to train me, okay? So, it wasn’t just “Send me a Superman story.” It was “Send me an idea, and then let’s talk about it.” And so, I’d send him an idea, a plot, a couple of pages of plot and he’d call me up and we’d talk about it and then also after that when I would send in my little drawings with the dialogue he would call me up and we would go over it. Panel by panel. Word by word. We had a regularly scheduled phone call every Thursday night and then he would call me any other time he needed to.

Well, these conversations quickly got into, “You f---ing retard! You stupid bastard! What is this supposed to be? You can’t spell this word! Blah, blah, blah.” Oh, my God. Just screaming at me. So, we’d have these 3-hour sessions where he just screamed at me the whole time. “What’s this man holding? It looks like a carrot. Is that supposed to be a gun?” Anyway, the words, “f---ing moron” were used with great frequency. I mean I needed this gig. I was helping to support my family and keep us from losing the house and all that stuff and so I didn’t know what to do. Usually these conversations just went along and ended up with me saying, “I just can’t do this. You just need to get somebody else,” and he would always say, “No. That’s all right. I’ll give you one more chance.” And to my face he used to call me his “charity case.” He said, “Well, your family would starve without this, so we’ll give you another shot.”

World's Finest Comics (1941) #162, main story written by Jim Shooter.

Stroud: What a guy.

JS: He called me his charity case. So, this is not a nice man. I remember one time I was in the office and his assistant was Nelson Bridwell and boy, he tortured Nelson. He just was awful to Nelson. I remember that I was doing this story. I think it was a World’s Finest story…I can’t remember. I think I just gave him a working name for the villain, just for the purpose of the plot, which was like the Black Baron or something equally stupid. So, when Mort called me up he said, “This is okay, I want you to do it, but I don’t like this name.” I said, “I’ll come up with a new one.” He said, “I have a name. This is the name. We’re going to call him the Jousting Master.” I said, “Yes, sir.”

So, I wrote this story and as it happened that was one of my trips to New York. I actually hand delivered it. So, Mort says, “Nelson, we’re going to teach you some things. Come here and read this.” So, Nelson reads it and he liked it. So, Mort says, “All right, tell me what you think.” So, Nelson says, “Well, I think it’s all pretty good, except the name is really stupid. The Jousting Master? Oh, come on, Jim, you know your names are usually much better than that. What an idiotic name.” And Mort just feeds him rope and feeds him rope. “Oh, tell me, Nelson, why isn’t that name good? I want to hear your analysis.” And he strings it along and strings it along and strings it along and I’m trying to “Ixnay, Nelson.” Oh, God. (whispering) “Nelson. Shut up!” And finally, Mort says, “I created the name.” I thought Nelson was going to die right there. He was all white. Anyway, Mort was like that to him all the time. It was horrible. He was a monster. He really was. (Chuckle.) I was at a convention and I met the guy who wrote Superman. Schwartz. Alvin Schwartz?

Stroud: Alvin. Yeah.

JS: I met him. I was introduced to him and he said, “You worked with Mort?” I said, “Yeah.” He said, “I quit because of Mort. That bastard! That son-of-a-bitch! Blah, blah, blah! He was an asshole! Did you quit because of Mort?” I said, “Yeah.” “Good for you!” And we bonded. (Mutual laughter.)

Stroud: Part of the same club.

JS: But anyway, Mort was fierce. He was nasty. The apocryphal story of his funeral was that they couldn’t find anybody to do the eulogy and finally some guy who had known him a long time got up and said, “Well, his brother was worse.” (Mutual laughter.) And while I’m sure that’s apocryphal, I mean I’m telling you, not many people would argue with it. He was something. Remember, I’m 14, and the big, important vice-president man from New York calls me every Thursday to tell me I’m retarded. At first, I really felt bad. I really felt terrible. And then I got to be 17 and I started thinking, “If I really sucked, they wouldn’t keep sending me these checks.”

Stroud: That’s right.

JS: Now here’s the punch line: Years later, Nelson told me that Mort used to brag about me. He’d go around to all these other editors and talk about his protégé and how he could give me any character, any story, I’d do it, it was usable. He never had to edit much, there was never a re-write, I did the layouts, I could do covers… And he would brag about me. I was a star. And when I found that out, I was like, “You son-of-a-bitch!” And then I met Cary Bates, who also worked for Mort, and the first time I met Cary Bates and was introduced to him, “Hi, Cary,” he said, “I used to hate you.” I said, “Why?” “Because Mort would call me up and say, ‘You f---ing retard! Why can’t you write like Shooter? You’re an idiot!’” And he’d just scream at Cary. I said, “Cary, he’d do the same thing to me. He’d say, ‘Why can’t you be like Bates? Everything he does is so polished.’” So, you know, that’s Mort. But, as you said, he taught me so much stuff. Not only about the writing, but about the art, about the coloring, about the whole business, about how to run a business, about licensing.

In fact; little known fact, when the Batman TV show was on and I’m like 15, Mort called me up and said, “I’ve arranged for you to write an episode of the Batman TV show.” “Wow! Holy cow!” So, they send me some scripts, some background material, samples and stuff, and I thought out what the deal was and I made a proposal and they liked it and I was just going to start writing my first TV script and they canceled the show. (Laughter.) So, I never got to do that. That’s another thing I was thinking later. “Wait a minute! If I sucked so much he wouldn’t be trying to get me these opportunities.” So, I started gathering that it was just kind of his way.

Adventure Comics (1938) #355, main story written by Jim Shooter.

Stroud: Yeah, put the pieces together. Were there any other editors you worked with at all or was he pretty much it at DC?

JS: Well, first of all I really loved Julie Schwartz. He was a great guy in a lot of ways. I ran into a couple of problems with him, but we got over it and we became buddies. Toward the end of his life I’d meet him for lunch in the city. He was like Mort in the sense that he would be insulting, but it was this outrageous, always in fun, kind of like a banter thing. But anyway, my first experience with him was this: Mort called me up and said that Julie, who was a lifelong friend of his, wanted to use me on the Justice League. And I said, “Okay, sure.” So, he said, “Come up with a cover and write a plot.” So, I came up with a cover and wrote a plot, and I sent it in and it was given to Julie and time passed and I finally asked Mort about it and he said, “Oh, he didn’t like it.” I said, “Okay.” I was working on the Legion and Superman, so I didn’t care. Then several months later, they used my cover! No money, they just used my cover. “Whoa! That’s dirty.” So, I was appalled by that, but then years later we worked together and that had its ups and downs, but ultimately, we patched it up and became buddies.

Stroud: I can see why the reaction would be what it was.

JS: I thought it was kind of dirty pool. The business was different then. Editors were cigar chomping guys whose job it was to keep you under their thumb so that you would never ask for a raise. I have another story about raises if you have a minute.

Stroud: Sure, please.

JS: This was told to me by Nelson and I believe it’s true. When I sent in my first three stories, one was 24 pages I want to say, and the other was a two-part story, so I think it was 46 pages total, this two-part story. Mort bought all three stories, but he bought the two-parter first (Note: This story became Adventure #346 and #347) and then a little bit later said, “Oh, I want to buy this other one, too,” (Note: This story became Adventure #348) and he sent me a check for that. So, the first story I sold was 46 pages, for which I was paid $200.00. Then, for the 24-pager he paid me $100. So that comes out to something under $4.50 a page for those. It was manna from heaven for us because it literally saved the house. I had no idea what the check was going to be for and even though it was only $200.00 that was all right, that was like a godsend.

Okay, so I’m going along and I think the next thing I wrote was a Supergirl story, 12 pages, and he sent me a check for $75.00. I just got these checks and they were not very big. (Chuckle.) Then suddenly, out of nowhere, the rate doubled. It went to; I think $8.00 a page. And I never knew why and with Mort you didn’t ask questions. So years later Nelson Bridwell told me that Edmond Hamilton somehow found out what I was getting paid, which was way substandard and went into Mort and threw a fit. He said, “It’s bad enough you’re using child labor, but do you have to rip him off, too?” (Laughter.) And shamed him into giving me a raise, and then after that I got a couple more raises. I think I ended up with $14.00 a page, which was kind of normal in those days. I don’t think that story is apocryphal. Nelson told me that and I believe him; that Hamilton went in and championed my cause, (chuckle) and I was the guy that was taking his job. I was doing the work that he might be doing. I don’t think he needed the work, though.

Stroud: It sounds right in character, too, based on some of the other things I’ve heard, so I don’t doubt it for a second.

JS: I agree.

Adventure Comics (1938) #346, written by Jim Shooter.

Adventure Comics (1938) #347, written by Jim Shooter.

Adventure Comics (1938) #348, written by Jim Shooter.

Stroud: Did you ever think to try your hand at any other genre? It seems like all you ever did was super-heroes and just kind of stayed that way.

JS: Well, you know that’s what was there. They wanted me to do the Legion and Superman. Fine. So, since I was in commercial comics, that’s what I did. When I left DC, because finally Mort just pushed me over the edge, what I did was I called up Stan. I said, “I’m a comic book writer and I need a place to work.” “Where do you work?” “DC.” “We hate DC stuff.” I said, “I’m different. Around there they call me their ‘Marvel writer,’ and they mean it as an insult.” He said, “Come up and talk to me.” So, he told me he’d give me 15 minutes. Three hours later I walked out with a job, because Stan and I got into talking about what comics were and what they ought to be and so forth, and we agreed. Interestingly, Stan and Mort really weren’t that different philosophically except that Mort thought the readers were 8 years old and Stan was trying to write for older people. College students, himself, things like that. But in terms of the fundamentals of introducing characters and all the building blocks, it was exactly the same. They both were well-schooled in classical structure and all that.

Stan Lee & Jim Shooter.

So, at any rate, to work for Stan I had to live in New York and that just didn’t last. I couldn’t. A kid from Pittsburgh, I was 18, I had no money, I’m trying to find an apartment. I finally said, “I can’t do this. I’ll come back someday after I’ve built up a grubstake.” So, I think I only worked there three weeks, and then I felt like I’d burned my bridges at Marvel and DC. Mort wasn’t talking to me any more because I’d defected and I felt like I’d kind of screwed Marvel over, so now I’m looking for work. I thought, “Well, what can I do?” Other than comics I’m maybe qualified to flip burgers.

Stroud: (Chuckle.)

JS: Seriously. A high school diploma. No experience in any useful thing, other than comics, and so I ended up doing jobs like in a lumberyard and Kentucky Fried Chicken. Things like that. But, miraculously, out of the sky, I got these calls from advertising agencies. “Are you the guy that does comics?” “Yeah, that’s me.” And so, I ended up doing advertising comics for companies like U.S. Steel and Levi’s and other substantial things. So, when you’re doing that, you can’t just do the superhero thing. It doesn’t fit. It’s not appropriate. So, I had to really kind of stretch myself and learn how and I actually got pretty good. I got good at understanding the need of the client and finding a way with words and pictures to get that over. And that was really good experience, because then I felt like I could do anything, and after that I did. I wrote children’s books, I’ve written animation developments, toy developments. I designed a float and a balloon for a Macy’s parade. All kinds of stuff. I’ve done film development stuff. I’ve never had a movie on the screen, but it’s mostly been concept doctor kind of things. I was hired by Fox and they had a couple of properties and they didn’t know what to do with them, so I fixed them for them, but somewhere between my writing that treatment and them getting together the 80 million bucks it would take to shoot it, something happened. In any case, I did all kinds of things. I think to this day I probably am somewhat rare among comics guys because I can give you cute, cuddly little furry animals in the forest story, or I can do superheroes, or anything in between. When you’re a freelancer you learn to say yes. Basically, people call you up and say, “Can you do this?” “Oh, sure I can.” Then you figure out how to do it.

Amazing Spider-Man Annual #21, co-written by Jim Shooter.

Stroud: "No problem". Gotta keep those checks coming in.

JS: Absolutely. So, I’ve done all kinds of stuff.

Stroud: And it sounds like that was an outstanding training ground for you even though it came out of left field.

JS: It was good and also all the stuff that Mort taught me was good because I found that I could apply it to other things. If you have a really good solid foundation in story-telling, then you can go a lot of places with it.

Stroud: Sure. It just gives you that basis and then there’s a versatility that leads from there. You’ve been both a creator and a staff guy. Which one was better do you think?

JS: I don’t know. (chuckle.) I like writing.

Stroud: Or is that an unfair comparison?

JS: It’s a different thing. I mean I do like…if it’s really going well, if your company is not under duress and you’re really kind of marching from victory to victory then that can be a lot of fun, because you have the feeling that you’re conducting the orchestra and you’re doing something bigger than you could ever do by yourself. You’ve got all these guys getting out the work together. So that’s good. I think that at Marvel for a long time we were just on this unbelievable series of victories. We went from almost dead to 70% of the market. In a market that was skyrocketing. Everybody was increasing. We were increasing that much faster. We almost took over DC comics. Bill Sarnoff called me up and said, “Would you be interested in licensing the DC characters for publication?” “Say what?” “Well, you guys seem to know how to do comics. You make money publishing. We lose a fortune publishing, but you don’t do any licensing and we do great numbers with the licensing. And your licensing is pathetic, so why don’t you publish and we’ll license?” And I said, “Great. But you need to talk to the president of the company and not me.”

So, I put him together with the president. The president turned him down. (Laughter.) And I went up and I said, “How did it go?” He said, “I told him we don’t want those characters. They can’t be any good. They don’t sell.” “Ahhh! Ahhh!” I said, “No, no. We can make a fortune with these characters. We know how to do it.” He said, “Put together a business plan.” So, I put together a business plan. We were just going to publish seven titles. Hire one editor, two assistants, a couple of production people and just do the seven biggies. You can guess. And I put together this business plan and it showed us making millions of dollars over the first two years. So, the president looked at this and he pronounced it ridiculous. He sent it to the circulation guys and said he wanted them to analyze it. So, I was called to a meeting and the circulation guy comes in, “This is ridiculous.” And Galton, the President, says, “I knew it.” But the circulation V.P., Ed Shukin said, “We’ll do double this!” (Mutual laughter.) And so, we started the negotiations to license the DC characters. We were going to become the publisher for DC comics and they were going to do all the licensing. We were going to get some little percentage of increase in licensing or characters or something. Then that’s when First Comics sued us for anti-trust. When you’re already 70% of the market, and you’re about to devour your largest competitor…that’s not good. So that all fell apart, but it was a wonderful couple of weeks while it lasted.

Stroud: Oh, goodness, yeah. You’ve been directly involved in creation of new publishing companies over the years like Acclaim and DEFIANT and so forth. What was the comparison of that to working for the big two, for example?

Black Panther (1977) #13, co-written by Jim Shooter.

JS: Basically, when Marvel changed hands and was bought by New World, I did not like those people. Actually, I didn’t like the people who sold it to them either because whenever a company is being bought and sold, most often what happens is that your rank and file is sold down the river. All I had to do was join in and help the upper management screw the people and I would have probably ended up rich, but I ended up…if you have any integrity in that situation, then you become a labor leader. And that’s what I was. I threatened class action suits to the management. I railed against them. They were doing things like cashing out the pension plan and changing the health insurance and making it much worse and they wanted to retroactively cancel the royalty program. You can’t do that. You can’t just stop paying royalties. You’ve got nine months or 10 months worth of books that people created on the understanding that they were getting royalties. You can’t just not pay them.

I ended up jumping up and down in the hallway, in the intersection between the financial officer and the president and the executive vice president and the lawyer’s offices, jumping up and down screaming “class action suit,” and they finally decided to cave in on that one. Anyway, I wasn’t making myself popular with the upper management and then when New World took over they were even worse. They knew that bad stuff was going on and they were okay with that. So, I made them fire me because I wanted the severance pay. So, then I needed a gig. First, I tried to buy Marvel and put together the Marvel Acquisition Partners and we tried to buy it and we finished second to Ronald Perelman. We were the only other bidder. Since that didn’t work out I looked around to raise money to start a comic book company and started VALIANT, but it was pathetically undercapitalized. With VALIANT it was the best of times, it was the worst of times. I really felt like while I was there I was doing some of the best work of my life. A lot of guys were chipping in and were fully behind me, but the thing is we had no money and so the only thing we had to fight with was man hours.

So, I would be there at the crack of dawn every day and I would be there when I couldn’t keep my eyes open any more. I went 400 days in a row at one point and did nothing but sleep and work and have a sandwich on the run. I didn’t get my hair cut. I didn’t have time to get a haircut. My hair got long. I had to wear a baseball cap to keep it out of my eyes. People would laugh. They’d say, “Well, what did you do for Christmas?” “I worked all day.” I was in the office. So were 14 other people, by the way. I worked Christmas and Thanksgiving. Everything. It just went on and on and on and, finally, we fought our way out of it. We started to make money. Money was rolling over the gunwales. $2 million dollars pre-tax profit a month! And then of course the evil bankers and lawyers stole it from me. It was a white-collar crime. I mean it involved falsifying documents and lying under oath. It was definitely a criminal action, but they got away with it.

Stroud: Unfortunately, it takes capital to fight those kinds of things.

Archer & Armstrong (1992) #0, written by Jim Shooter.

JS: Yeah, and not only that, my partner, Massarsky, got married to the banker! (Chuckle.) I remember that just after we started out it was a couple of days before Christmas and he says, “I want to tell you something.” “What’s that?” “I’m dating Melanie.” “What! You’re what?” “I’m dating Melanie.” And they ended up becoming a couple, and of course between them they had a controlling interest. Originally the three operating partners, Massarsky, a guy named Winston Fowlkes and me, owned 60% and the investors owned 40%. Well, once Massarsky went over to her side, then it was 60-40 the other way--and of course he’s literally in bed with her. So, that’s why we ended up doing Nintendo comics. I didn’t want to do Nintendo comics. (Chuckle.) I didn’t want to do wrestling comics, but Massarsky, who was a lawyer, represented Nintendo and he represented the WWF and so he was sitting on both sides of the table in those negotiations and his girlfriend-to-be-wife went along with whatever he said. They called the shots.

So, I find myself doing Nintendo comics, which I can do. I can do whatever you want. Whatever you need. Anyway, all those things failed, and we ended up deeply in debt. We’ve way exhausted our original stake. Now that means that we’re technically in default, so that the investors, the venture capital company, obviously they’re doling out dollars day by day to keep us afloat so we turn it around, but that means they also control everything. We were doing things like having to account for every hour of every person on staff, fill out charts and forms and anybody who didn’t do enough work to justify their salary had to be cut. Well, I was there 18 hours a day, so what happened was that even though I was the highest paid guy, I would always outdo my “quota,” by double or triple. So, what I would do was I would take work that I did and pretend that other people did it. You’d see credits for Bob Layton, editor. Nah. You’ll see coloring by so and so. Nah. It was me, spreading credit for my over-quota work around so that everyone could keep their jobs. Things like that were just to keep everybody employed until we turned it around, but then we did turn it around and I thought, “Hey. We made it.” (Chuckle.) But as soon as we made it, then they wanted to cash out and that involved getting rid of me. So, I was gotten rid of. And ended up with a tiny little settlement that wasn’t enough to pay for my lawyer.

Stroud: Adding insult to injury. Doggone.

JS: Yeah. DEFIANT was easier to start because it was easier to raise money after I’d had the success with VALIANT. But that was a bad time. That was when the market collapsed and Marvel sued us and it was ugly. And then I went to Broadway. And that was fine. I thought we were doing all right until they decided to sell the entire parent company to Golden Books, which promptly went bankrupt. (Laughter.)

Stroud: Perfect.

JS: We were part of Broadway Video Entertainment, which was sold to Golden Books and we just got shipped along with the deal, and then they got rid of us also. They didn’t want to be in the comic book business and they were busy going bankrupt.

Stroud: (Chuckle.) A couple of distractions there. Oh, golly.

JS: What a career!

Stroud: Yeah, no kidding. At one point in there weren’t you collaborating with Steve Ditko on something?

JS: Well, when I was at Marvel, the legend is that I drove away all these creative people and that’s baloney. Basically, I brought back all the creative people, but when a Frank Miller goes over to DC and does a Ronin or Dark Knight or something like that, it gets a lot of attention. No one notices that he comes back and does Elektra and other things for us. Byrne eventually went over there, but very few guys bailed out and we got back guys that hadn’t worked at Marvel in years. Starlin and Englehart, Roy Thomas and Bernie Wrightston, and I can’t even remember them all. Lots of guys. Kaluta. We felt like we had the who’s who of creators.

Stroud: It sure sounds like it.

JS: We really did. We used to talk about it. “Well, who would we want, that we don’t have?” Usually the names that came up were Jose Luis Garcia Lopez and George Perez. Accent on the first “e.” Perez left on good terms. He actually wrote me a long apology letter saying that he’d wanted all his life to draw the Justice League and DC offered him the Justice League. Hey, God bless you, George, go do it. So we…I forget the question. (Laughter.)

Dark Dominion (1993) #0, co-written by Jim Shooter & Steve Ditko.

Stroud: Oh. I was just wondering about your collaboration with Ditko.

JS: Oh, Ditko. Right. So, Steve came back. Steve had a real ugly parting with Marvel and hated us and all that stuff like that, but I met him. I met him up at Neal’s, I think. I talked to him. I said, “You know, Steve, you’re a founding father. If you ever, ever need anything. If you want anything, want the work, whatever, the door is always open. Any time.” I said the same would go for Kirby, except that he was busy suing us, but, whatever. But for the founding fathers, as far as I was concerned, if there is nothing I’ll make something for them. So, to my amazement one day Ditko shows up and wants work.

The trouble with Steve was he’s really fussy about what he would do. First of all, he’d never touch Spider-Man or Dr. Strange because that just gave him bad feelings. Second, if it was a hero that had any flaws, he wouldn’t touch ‘em. “Heroes don’t have flaws. Heroes are heroes.” I’m like, “Oh, geez, you did Spider-Man. He had flaws.” He said, “Well, he was a kid then. It’s okay. He hadn’t learned anything yet.” *sigh* Finally we settled on Rom, SpaceKnight, which seemed noble enough for him to do. He did a good job on that. It was great. He did other little things here and there, and when I left Marvel they stopped giving him work! They basically threw him out.

Stroud: Oh, man.

JS: Now Steve, his stuff was old-fashioned and he wasn’t a fan fave and I’m sure that contributed to the book not selling as well as it might have, but they wouldn’t give him work! He came to me at VALIANT, practically…Steve is not a hat-in-his-hand kind of guy, don’t get me wrong, but he really needed a gig. And so, at that time I think we were doing wrestling books and I said, “Would you do these?” “Yeah.” So, he did some wrestling books. He did some nice work for us, and we got along great. He’s a very, very tough nut. When I went to DEFIANT I asked him to describe to me the perfect kind of character. I thought I created that when I did the Dark Dominion thing and he agreed to draw it and he got about halfway into it and he came in and dropped it on my desk and said, “I can’t do this.” I said, “Why not?” He said “It’s Platonic, and I am an Aristotelian.” I said, “What?” He had to explain that one to me and he said, “Well, Plato thought there was the real world and then this invisible world and I’m Aristotelian—I believe that what you see is what you get. That’s all there is. Reality. This story has a substratum world and I’m not drawing it.” I said, “Oh…” (Chuckle.)

But anyway, I still love Steve and I would do anything for him. Great guy. He’s a tough nut, though. At Broadway, when I had a little more latitude I tried to talk him into letting us publish Mr. A. I said, “You keep all the rights. We don’t want any rights. No, no, no, no. We just want to publish it. That’s all. And if you choose to, if you decide, we would like you to consider giving us, for compensation, a temporary right to do film or television. And you get the say over that if you want. Steve, I’ve got money now (that is, Broadway did), and I want to publish Mr. A.” Because Mr. A was like his greatest thing. And he was so suspicious of dealing with a company, he was just sure that somehow, we’d get our hooks into Mr. A and it would be taken away from him. Eventually, though, he just sort of started to come around to the idea, and he actually brought me a Mr. A story and said, “You read this and tell me if you’ll publish it exactly as is word for word.” And I read it and I said, “Yes, I will.” Well, about that time we were getting sold to Golden Books and the window closed.

Stroud: Oh, boy.

JS: Yeah, but Mr. A is cool and I love Steve and I wish we’d done it.

Harbinger (1992) #1, written by Jim Shooter.

Stroud: Another one of those opportunities that may or may not arise again, but that’s fascinating. It really is.

JS: He’s a terrific guy. We had a party once at the office. I looked around VALIANT one day and I realized that we had all the old guys. Mostly because they couldn’t get work anyplace else. I had Stan Drake, I had Don Perlin, I had Steve Ditko, and I had John Dixon, all these guys that had been around for awhile. We didn’t have money. I was doing this on my credit card, but we got a catered lunch from the deli. Stan Drake came down and Herb Trimpe was there, I think. There were a lot of guys there and of course we had all the kids, the young guys, the Knob Row guys, the guys just out of the Kubert School, and they were all with their eyes like saucers, and we had a ball.

We took a lot of pictures, but Steve would not let his picture be taken. He said, “It’s about the work, not about me. I don’t want my picture taken. I won’t stand for it.” “Okay, okay.” But he had a good time. The old guys, back in those days, there was this greater respect, I think. These days the kids act like they invented everything. Take ballplayers. If you see a ballplayer he’ll talk about his heroes when he was a kid. Ernie Banks and Mickey Mantle. He’ll talk about the older guys. “Don Mattingly taught me so much.” But comics guys, they seem to resent that there was anybody (chuckle) before them. But when you get all these old guys together, they were actually honored to meet each other and respectful and it was just cool. It was like an old-timer’s convention, but we had such a good lunch. It was just great.

Stroud: True gentlemen of the day.

JS: Gentlemen. And you now what? I started out at age 13 in 1965 and everybody I worked with was older and was like that. And then as I got older in the business and the business got younger around me I kept being astonished that people were untrained, unskilled, (chuckle) unprofessional and arrogant. Undisciplined. I was like, “What happened? What happened?” I think what happened was when the new generation came in there’d been a gap. There were guys who were 50 and there were guys who were 20 and there was no one in between. And so, when that bubble passed down the pipe and all of a sudden, all the young guys weren’t even trained yet are editors-in-chiefs and big shots and we missed a generation. The generation that should have been in charge wasn’t there.

Stroud: A lot was lost. Russ Heath was speculating to me. He said that he thinks that one of the things that might have happened that coincides with what you just said was that back in the day there used to be such things as apprenticeships and he said, “You don’t see that any more. Somebody will knock out something on a computer and sell it and voila! I’m a pro.” No disciplined approach. I think you corroborated that.

JS: Yeah, I believe that’s true. Neal made such a difference in the business because he had that studio and the guys just going there and hanging around learned so much.

Stroud: Oh, exactly. The Crusty Bunkers and all that other good stuff. Do you still hit the convention circuit at all, Jim?

JS: Well, I didn’t for years because I really didn’t have any reason to. I went to one because the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund asked me to come to be the celeb at their booth to directly draw people in to donate money. I said, “I don’t think anybody even knows who I am.” I went there and had a long line and it was great. So, I did that. I did one or two others. Each one of them was for some strange reason. I didn’t have any real reason to be there. But now, with the Legion, I’m getting a lot of requests and DC is actually encouraging me to do some of these, so this year I might go to I think four of them. DC has asked me to go to the one at the Javits Center in April, I guess it is. And in May; I’ve been friends with these guys over in England forever and they kind of impressed me into service. It’s like the War of 1812 again.

Marvel Graphic Novel #16 The Aladdin Effect, co-written by Jim Shooter.

Stroud: (Laughter.)

JS: I’ve got to go over there in May and I’m definitely doing Baltimore. I did Baltimore last year. That’s in September. The reason I want to do that is because it looks like the first time that the Legion inker, the penciler and me will all be in the same place at the same time. So just to be there with Francis and Livesay; gotta do it.

Stroud: Oh, yeah. Sounds like fun.

JS: I haven’t been doing a lot of conventions. You know artists go to these conventions and sell their sketches and stuff and I guess they make money. I go and I lose three days of work.

Stroud: (Laughter.) Good point. A writer’s wares are somewhat less tangible. Not too many people wanting a quick script.

JS: It’s really funny. When people want autographs artists always think of all these witty things to put and I can’t think of anything. “Uh-h-h. I don’t know. ‘Best wishes.’” I can never think of anything on the spot like that. “I’ll take it home with me. Give me a couple of hours. I’ll come up with something.”

Stroud: (Laughter.) Cogitate over it for awhile. I like it.

JS: You know what? It’s true. If you’re a writer, people expect it to be good, to be brilliant, so you think, “It’s not good enough!” Even if I write a letter; “I’ve got to make sure everything’s spelled right.” You become; “I’m a writer. What will they think if I make a mistake?” Other people just bang out a letter. Not me. It’s all day.

Stroud: (Chuckle.) Yeah. Gotta submit it for editing and…

JS: Yeah, you’ve got to think of some witty approach, and build some drama into it…

Stroud: Make sure everything fits. (Laughter.) Well, Jim, you’ve been an absolute joy to talk with. I see I’ve burned up well over an hour of your time, which is probably above and beyond the call of duty.

JS: That’s all right. I work at home now. I don’t get to talk shop ever. It’s easy to get me to talk.

Marvel Super Heroes Secret Wars (1984) #8, written by Jim Shooter.

Jim Shooter in 2008.

Marvel Treasury Edition (1974) #28, co-written by Jim Shooter.