An Interview With Neal Adams - Legendary Artist and Creator Rights Advocate

/Written by Bryan Stroud

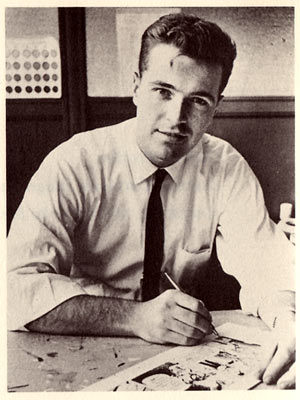

Neal Adams sitting at his drawing table in 1966.

Neal Adams (born June 15, 1941) is an American comic book and commercial artist known for helping to create some of the definitive modern imagery for DC Comics characters such as Batman and Green Arrow; as the co-founder of the graphic design studio Continuity Associates; and as a creators-rights advocate who helped secure ownership rights for creators from all walks of the comic industry. Neal was inducted into the Eisner Award's Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame in 1998, and the Harvey Awards' Jack Kirby Hall of Fame in 1999. At the age of 76 (as of this writing) Mr. Adams is still going strong with new comic work being published and a full tour of convention appearances every year.

Who hasn't heard of Neal Adams? His appearance on the scene was truly a blockbuster event and he changed comics nearly single-handedly with his photo-realistic style and attention to detail. His work for creator's rights cannot be overlooked either, nor the important work that came out of Continuity Associates. I actually hadn't seriously considered reaching out to Neal, reasoning that he'd been interviewed any number of times, but during a follow-up conversation with Carmine Infantino, he asked, "Have you talked to Neal?" "Well, no." "You should give him a call. Tell him I sent you." How could I refuse that offer? So, I initially sent Neal an email with the subject, "Carmine sent me." He responded, agreed to an interview and gave me his phone number. As you'll soon see, it was effortless. Neal had plenty to share.

This interview originally took place by telephone on May 28, 2007.

The Adventures of Bob Hope (1950) #107. Cover by Neal Adams.

The Adventures of Bob Hope (1950) #108. Cover by Neal Adams.

The Adventures of Jerry Lewis (1957) #103. Cover by Neal Adams.

Bryan Stroud: When did you start at DC exactly?

Neal Adams: Golly. There must be some historians around who can tell you that. I don’t know. It was in the 60’s. I don’t know when that was, but I’m sure some geek around will know exactly when that was, probably the month and the day.

(Note: Wikipedia tells us it was 1967)

Stroud: Oh, no doubt. Carmine was telling me that he knew more than one person who worshipped the ground you walked on.

NA: That’s ‘cause I walk in very special places. I don’t walk along those cold cracks. (Chuckle.)

Stroud: He also told me…this one kind of surprised me, he said he first discovered you in the bullpen working on Jerry Lewis, of all things. Is that true?

NA: No. I was first introduced to Carmine…Carmine was, of course, as with many comic book artists, a bit of a hero of mine, because when the shit hit the fan in the country when the book “The Seduction of the Innocent” came out…

Stroud: Ah, yes, good old Doc Wertham…

NA: Many, many artists had to desert the field, or were hidden among the cracks and crevices in various places, like Al Williamson was doing, I guess, ghosting for certain comic strip artists and I guess he would do a comic book every now and then and Alex Toth went to California to do animation, and all these guys really disappeared, and the few guys that were left were the guys at DC comics. There was Joe Kubert, there was Russ Heath, there was Carmine, there was Gil Kane (known as Gil, Eli Katz was his original name).

Stroud: Ah, yes, yes.

NA: And Carmine, had a very unique style. He then was doing the Flash and his style kind of got covered up, but I was a fan of his original style when he was doing Pow Wow Smith and some of those other things, so as a fan, you know, to meet Carmine…and Carmine was actually working on staff…not really staff, he had a desk in with the romance editor…what’s his name? Miller.

Stroud: Oh, Jack Miller?

NA: Jack Miller, Jack Miller and his girl assistant, and he was in there when I first came to DC comics. I came to DC to try to get work with Robert Kanigher. The ‘much beloved’ Robert Kanigher.

Stroud: Sometimes referred to as “The Dragon?”

NA: Who was a beast in human disguise. And I got to work with Bob, partially because he had lost Joe Kubert, because I had recommended Joe to do a comic strip called The Green Beret that I had been asked to do, and the comic strip people had no idea who the good comic book artists were, and when I realized that I really couldn’t do the strip…I was doing Ben Casey and I couldn’t handle two strips. I took the people from the syndicate and the writer down the path of possibly recognizing that there were such a thing as comic books and rather than try to find somebody in the Ozarks, perhaps they ought to go to some of the best artists that were left in comic books and among which were Joe Kubert, who was the perfect guy for the strip.

The Ben Casey strip from November 26, 1962. Art by Neal Adams.

A Ben Casey strip from 1964. Art by Neal Adams.

Stroud: Oh, sure. All his war comic experience.

NA: Yeah. So I recommended him for The Green Beret to Elliot Caplin, the writer of the strip. They interviewed. They did it and Joe was working on The Green Beret for the longest time and Bob Kanigher, coincidentally, was a little short on artists. I had ended my syndicated strip, which was based on the Ben Casey TV series, and things were just a little bit slow for me and I had been doing some stuff for Jim Warren - and I realized I was putting way too much effort into this Jim Warren stuff and it wasn’t worth it to me - and I thought maybe I’d give it a crack at DC comics in spite of the fact that when I was a teenager and I left school, they wouldn’t even let me in the door.

Stroud: Oh, golly.

NA: Yes. It was a very bad time. An old fella came out to meet me, a guy named Bill Perry and met me in the lobby and I showed him my samples, just to try to meet an editor and he told me that he couldn’t even bring me inside. It didn’t matter if my stuff was good, it didn’t matter anything. They weren’t interested.

Stroud: Oh, that’s surprising.

NA: No, not at all. For those times it was very typical.

Stroud: Just not enough work to go around, I guess.

NA: Not enough work to go around and they were feeding the mouths that were faithful to them, and they just weren’t interested. Nobody really got in easily. Once in awhile some guys broke through, like John Severin did a little work for a while, but it didn’t seem like that lasted and I guess he found something else in Crazy Magazine. But when I went there as a teenager, this guy, this very nice old guy just told me I’m wasting my time. As far as they were concerned, any minute the comic book business would end.

Stroud: Wow.

NA: Things were not so good.

Stroud: Boy, I guess not. That just blows my mind to consider it.

NA: Well, I’ll tell you another story that is actually coincidental to that story. Timely magazines, which later became Marvel, really wasn’t doing anything, and you didn’t even know where they were, and I was this 18-year old kid who was trying to get some work and so I thought maybe I could go to Archie Comics and work for Jack Kirby and Joe Simon, who were doing at that time The Fly and The Shield and a bunch of other titles for Archie Comics.

Stroud: Oh yeah, their adventure series.

NA: So, after failing at DC and searching around for nothing…I didn’t know where anybody was. I went over to Archie Comics and I tried to get work and I showed my samples and neither Joe Simon nor Jack Kirby were at Archie Comics. I met the Archie guys and obviously they felt sorry for me, because I was foolish enough to want to do comics. Nobody did. Nobody was showing samples. It was a dead field. And so they suggested I come back with some samples of The Fly, and I did. I came back the next week and they’d introduce me to either Joe Simon or Jack Kirby. So I came back a week later with my samples and it turns out neither one of them were there.

A panel from The Adventures of the Fly (1959) #4 - Adams' first commercial work.

Stroud: Of course.

NA: So I showed my samples to the guys at Archie and they looked at them sympathetically with kind of a sad look around their eyes, an embarrassed look, and they said “Well, why don’t we get Joe Simon on the phone for you?” And so they did. Now it turns out they had shown Joe Simon the samples I had brought in previously, and they got Joe Simon on the phone for me. Joe said to me, “Neal…young man, your samples are good. I’d use you on stories, but I’m going to do you a really big favor. I’m gonna turn you down, kid, because this is not a business to be in. It’s gonna fall on it’s face any day now and everybody’s gonna be out looking for other work and you want to get a job doing something worthwhile, so it may not seem like I’m doing you a favor, but I’m turning you down, and it’s the biggest favor anybody could ever do for you.” “Gosh, thank you, Mr. Simon.”

Stroud: How very gregarious.

NA: So the guys at Archie said, “Well, Neal, do you want to do some samples of Archie? And you know, maybe we can give you some work doing our joke pages or something.” I said, “Yeah.” So I came back with some samples and in the end I did work for Archie for the Archie joke pages for a couple of months, and that’s how I got my first work in comics, because Joe Simon turned me down.

Stroud: Son of a gun.

NA: The end of that story is, if you’d like to hear it…

Stroud: You bet.

NA: About 15 years later, or so, I don’t know exactly how many years it was, I made my way into comics and the world of comics had changed, the revolution was in, Neal had established himself as a gigantic pain in the ass, but a sufficiently talented pain in the ass that they put up with me, and I was fighting for the return of original art and royalties and all the rest of it and I was helping various people and I helped…I don’t know if I helped Jerry [Siegel] and Joe [Shuster] at the time or whatever. Anyway, I was up at DC, for whatever reason, and Joe Simon was there and I’m talking to editors and people that I know, and again I had established something of a reputation, good, bad or indifferent, whatever you may think of it, and apparently Joe Simon was up there and the word was that he was fighting a battle over Captain America and some other things, because he felt he owned certain properties and under certain circumstances, blah, blah, blah.

Superman (1939) #233. Cover by Neal Adams.

Joe Shuster, Neal Adams, and Jerry Siegel

Superman (1939) #317. Cover by Neal Adams.

Apparently he was looking for Neal Adams. So he was down the hallway somewhere, so I went and sought him out and introduced myself and he said, “Listen. Can I talk to you? I really have to get your advice on something.” And I said, “Well, DC has a coffee room. We’ll go to the coffee room and have a cup of coffee.” So we sat down and had a cup of coffee and Joe explained to me something of his situation with Captain America and the various characters that he felt he had a right to, and I listened to him and I said, “Well, okay, let me tell you this. First of all I can give you these two lawyers and I can give you this person here who seems to be fighting for graphic arts and I can tell you this, that you should begin by sending bills in and making a paper trail and establishing yourself with the people that you work with and the people who are in charge of the people that you work with as requiring and demanding that you didn’t have contracts, you have rights to these things, you have to create paper, and then you can go and see these people, although most lawyers won’t think much of this, there are a couple lawyers that you can talk to and also people who are associated with the National Cartoonist’s Society that you should talk to.”

So, I gave him a list and I wrote down the stuff. Anyway, so we got up. He said, “Thank you. You have no idea how much I appreciate this.” I said I have a pretty good idea. And so he shook hands and he was gonna leave, and as he was about to leave I said, “Excuse me, Mr. Simon.” He turned around, he said, “Yeah?” I said, “I’d like to introduce myself. My name is Neal Adams.” He said, “I know.” I said, “Well, let me tell you a story…” He had no idea, no idea that this was the same person that he had spoken to. Absolutely no idea.

Stroud: And what was his final reaction?

NA: His final reaction was, “I guess that wasn’t such very good advice, was it?”

Stroud: Oh, how the pendulum does swing. That’s funny. That’s just too funny. You actually have two U.S. postage stamps of your work now. How does that feel?

NA: Two? I thought it was just one.

Stroud: I think so, at least they gave you credit on it, there’s obviously the iconic Green Lantern one and then the Aquaman one is attributed to you also.

NA: Oh yeah? I don’t think that’s mine. I think that’s not fair to somebody. Somebody out there is not getting credit.

Stroud: That could very well be, but it does look a little like your style. I mean, I don’t have the artist’s eye, but…

NA: I don’t know. I thought it was just one.

Stroud: Okay. (Note: I discovered later that the Aquaman stamp was done by Jim Aparo.)

NA: It was very nice, don’t you think? Very pleasant to see that. Really not so much for me, but I think for an industry that was basically considered to be just one small step above toilet paper.

Stroud: Oh yeah, exactly.

NA: To have come so far that the stuff we have done in comic books is appearing on our screens for hundreds of millions of dollars, that is appearing on our postage stamps and on our television shows, that is essentially making a contribution to popular culture across the board.

Justice League of America () # 138. Cover by Neal Adams.

Green Lantern stamp issued in 2006. Art by Neal Adams.

Green Lantern (1960) #89. Cover by Neal Adams.

Stroud: Oh, absolutely.

NA: Quite incredible.

Stroud: Absolutely.

NA: Amazing.

Stroud: It was kind of funny, ‘cause…

NA: I had a little to do with that. (Laughter)

Stroud: You did, which is one of the reasons I was pleased to get the opportunity to pick your brain a little bit.

NA: But you were gonna say…

Stroud: Oh, I was just commenting…Carmine was even asking me…I think being part of the old guard it was just hacking out a living and he was asking me “Now how old are you?” I said, “I’m 44.” “Why all this interest in comic books?” I said, “Well, Carmine, I…”

NA: (laughter) I don’t think actually Carmine has absorbed the impact of what is actually going on here, of what a cultural change this is making. I think Carmine perhaps even thinks that there are illustrators out there doing illustration work when in fact there is a minority of illustration work out there. All the magazines that used to carry illustration work no longer do it.

The movie posters that used to be Bob Peak and Drew Struzan now are photographs for the most part. You get a Drew Struzan poster once in awhile, but really you know the illustration field, it hasn’t dried up, there’s certainly illustration work out there, but nothing like used to exist in the 40’s, 50’s and 60’s and before that. So the question today is what does an illustrator do? What does somebody who is really good and really professional and loves to create and draw, what does he do? Who would ever think that somebody would say “Do comic books?” It’s just a phenomenon. But that’s what’s happening. There are more illustrators and artists doing comic books, excellent comic books…there’s not even a question.

And then if you think of all the ancillary stuff, the computer games, the movies, the television, the t-shirts. I have people walking around who are proudly wearing Superman t-shirts. They’re not some 12-year old kid with some Superman t-shirt with a DC logo on it. There are people who are wearing stylish shirts and clothing with these various logos. It’s become a major part of our culture and is spreading around the world.

Stroud: Yes. I couldn’t agree more.

NA: It’s really quite phenomenal.

Stroud: It’s modern day mythology.

NA: Ah, you’re a writer, I can tell.

A Megalith sketch done by Neal Adams.

Challengers of the Unknown (1958) #68. Cover by Neal Adams.

Detective Comics (1937) #418 original cover art by Neal Adams.

Stroud: Oh, well, I dabble. Let’s put it that way.

NA: Well, what’s that “modern day mythology” stuff?

Stroud: (laughter) And perhaps I lift a little from your old compadre, Denny O’Neil.

NA: Oh, yes.

Stroud: In “Knightfall” he said something to that effect, talking about Superman being a modern day incarnation of Gilgamesh, I believe, but he says, “But you take Batman and what is he, really? Is he a hero?”

NA: Well, certainly Batman is a hero, but Batman is the antithesis of the superhero if you think in terms of what superheroes have become. You know, bitten by a radioactive spider is pretty much the standard. Batman is the opposite of Superman. You have Superman, who is the most powerful superhero there is, essentially and almost too unrealistic to consider to deal with and on the other end of the scale you have a person who is in fact not a superhero at all.

Stroud: Yeah, yeah…

NA: Batman is a NOT superhero. I don’t know who else is a NOT superhero and is successful. I mean there have been guys around who have put on costumes and have acted like superheroes, but generally they get themselves pasted. Batman succeeds where no one else succeeds. He is not, in any way, a superhero.

Stroud: Absolutely true.

NA: He wears a costume, but that’s to scare people.

Stroud: Yeah, yeah exactly. His primary method is fear, inciting fear.

NA: So you see between Superman and Batman the opposite ends of the scale, the whole of the comic book industry.

Stroud: Very much so. It’s kind of a shame after all of the efforts that you were able to bring forth that you were too late to save somebody like a Bill Finger, for example.

NA: It’s a, you know, more often than not, as much as I…I don’t look for these things, but what happens is that people don’t come to me and say…basically I say, “I’m at your service. I owe enough to this industry to be willing to say if you need my help, you just have to reach out and I’ll help. Whatever it takes.” And…just sometimes people have too much pride to ask for help and I understand that perfectly, you know. That’s just such a natural phenomenon, but people don’t ask, and when people ask, very often people will rally around and do things. It’s just very often the hardest thing in the world to ask. And so anything that I’ve been able to do has really been when a person is at the end of their line. “I can’t do anything else.” Call Neal. And then we turn things around, and everybody rallies, everybody comes to it, it’s just…

Detective Comics (1937) #395. Cover by Neal Adams.

Batman (1940) #244. Cover by Neal Adams.

Detective Comics (1937) #415. Cover by Neal Adams.

Stroud: It’s the right thing to do.

NA: Well, of course. No surprise.

Stroud: It’s no more complex than that.

NA: No.

Stroud: What’s right is what’s right…

NA: Exactly.

Stroud: I don’t know. The things I’ve read about both Bill and Bob Kane, you just shake your head after awhile…

NA: I don’t know, you know I think Bob Kane did kind of okay. He made a living at it. I don’t know. Yeah, he didn’t get rich, that’s true. On the other hand nobody was getting rich…well, that’s bullshit. I’m lying. I just started to lie there. (Chuckle.) It’s crap. It’s always been a Mom and Pop business, it’s always been shit, and the one thing that’s happened is it’s gotten a lot better.

You know, God bless the people who get into it now. It’s way, way better for them. For the guys who were in it at the beginning when it was going to be flushed down the toilet, you know the mere fact that they held on or they were able to hold on is a glory, in my opinion, but nobody expected it to survive and everybody was grabbing for whatever little piece of shit they could. You know they didn’t even have contracts. They had “contracts.”

You know Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster signed a contract, but when I got in they didn’t even have contracts. They were ready to go out of business. They had this statement on the back of the check that says, “We own everything.” I went to a lawyer and he said, “That’s not a contract. Just write “under protest” under it or cross it out. It means nothing. It means nothing in court. It’s not a contract.” So we went through that terrible time and it was like being in the Stone Age, it was unreal and it was…you can’t put a definition on it. And those guys who went through it, who suffered through it…you know God bless Bob Kane who was able to bring his Mom or his Dad down and bring a lawyer down and was actually able to get a contract. He is, as far as I know, the only guy in the business that actually got a contract.

Stroud: Yeah, for that era, as near as I can tell, you’re absolutely right.

NA: And he was paid for comic books he never did, he had other people do it, he was able to do it…he got royalties he got some kind of deal at the end, so he was able to take care of himself and they didn’t bother him when he did paintings with Batman on them and he did a TV show. You know Bob was all right. I don’t know so much about Bill Finger, but I hear he wasn’t so good for that.

Stroud: Yeah, like I say from what I’ve been able to gather Bill toiled in obscurity and unfortunately died the same way.

NA: But you know most of those guys went home at night and they kissed their wives and they watched the television and they lived a normal life and it was that kind of a business in those days. You just can’t compare it to today.

Stroud: Yeah. A different world.

NA: How could you find a Frank Miller back in those days?

Action Comics (1938) #400. Cover by Neal Adams.

Starfire (2015) #9 original cover pencils by Neal Adams.

Starfire (2015) #9 Neal Adams Variant.

Stroud: Yeah.

NA: I went through it. I tried as much as I could to help, I tried as much as I could to change it, it was a disaster and it needed every bit of help it could get. I wish there were more people that could repair the…broken animal that it was, but we came out of it. We came out of it the better for it. And I don’t know, is it because we’re America and we’re Americans and we have a better attitude? Why is it? Is it because we believe in heroes, is it because we’re optimistic, what is it about the nature of comic books that makes it such an American thing? It makes a universal thing, but it all really comes from America and to think that our greatest comic book superhero came from two little Jewish kids in Cleveland, Ohio, of all places is a wonderful story, so you know so as much as I get pissed off about it, you know I got up out of the fight and I had blood all over me and mud all over me, but you know around me everybody was smiling and moving forward, so I went and washed off and cleaned up and everything’s fine. (Laughter.)

Stroud: Absolutely and well, it was pivotal, the work that you did. More than one person has commented to me that the efforts that you put forth led to that sea change that was long overdue.

NA: Well, there you go. Somebody had to do it.

Stroud: It’s certainly something to be proud of. You kind of broke out on the Deadman comic, was it intimidating at all to be thrown a project that was started elsewhere? Did that bother you at all?

NA: Not at all. I was just accepting assignments and I thought it was wonderful that Carmine did that first issue and then Carmine wanted to be an art director and then he couldn’t do other issues and then they cast around and I was basically the only fish to be able to fry and to follow something like that and I just loved the hell out of it. I had to give up the Spectre at the time. I thought I was giving up something more significant, but Deadman turned out to be a pretty interesting project, and for me, remember I had done this soap opera syndicated strip based on Ben Casey. I wasn’t really that much of a superhero guy. I mean, you know, to me, superheroes are a little…if you punch somebody in the face, he bleeds and he falls down and you have to take him to the hospital to get him fixed and maybe he won’t get fixed and there’s lots of problems. It’s not that you’re battling in abandoned warehouses and nobody really suffers the blow. I don’t really do very well in that kind of thing. I’ll do it, because I’m a professional. But Deadman was a very interesting character. Once again not only not a superhero, but he’s dead. (Laughter.) He’s dead, man.

Stroud: Yeah, he’s certainly not pleased with his station in life…or death.

NA: Right. So it was my kind of comic book, because it had a real gritty sense of reality to it, so you’ve got to remember, too that a lot of those older guys came out of those times where there weren’t that many superheroes. I guess Carmine did superhero stuff, but he also did Western stuff, he did other stuff, too and he was also a tremendous designer and even his characters weren’t necessarily superheroes, you know. Flash was, I guess and he became famous for that, but I don’t know, Deadman sort of fit into that, you know, he didn’t have balloon muscles, he had real anatomy, he was a gymnast and a trapeze artist and so if I had to make the choice I’d have picked me first, but I think Carmine doing it really set up a great character and passing it on to me really said basically, “Dinner is made. Would you like to enjoy it?” And I said, “Yeah.”

Stroud: Great analogy. Now later on you actually took over scripting as well. What led you to that?

NA: Well, what was happening with Deadman was that you have a certain standard of writing, of given time, and it flows with the time, and in those days it was, “Here is a superhero; do a story about him.” You know, do a Superman story, do a Batman story, whatever it is, because there’s going to be hundreds of them, and you’re just going to do one, so you come up with a story, you know, bring somebody else into it…blah, blah, blah. To me, that’s not what Deadman was about. Deadman was about Deadman.

Maybe it had an end, but it didn’t matter if it had an end, but the idea was you wanted to do the story about Deadman, you didn’t want to do the story about Fred who is a divorced parent or whatever the hell it is. It should be about Deadman, it should circulate around Deadman. It seemed like Deadman became something that everybody threw up in the air and everybody took shots at it. Everybody wanted to write a Deadman story because it was the only book at DC comics that was getting any attention. So Bob Kanigher wrote a two-part story, and I went to my editor at the time, who turned out to be Dick Giordano, because it had been passed on to Dick after Miller had left under dubious circumstances. I don’t know how to say that the right way. It wasn’t good.

So Dick had it, and Kanigher wrote a script, he wrote a 2-part script, and Kanigher did kind of that thing that Kanigher does. He sets up a situation, the character fails at the situation one time, then he fails at the situation a second time and then he succeeds. If you read Bob’s stuff, that’s how it works. I was a Bob Kanigher fan and the longer he made the story the more the guy would fail until he succeeded. So what I did was I took that story and I compressed it into one book, the two book story because it was really only worth one book. I took the story to my editor and I said, “Dick, it took a lot of work to take that story from two books into one, but if I’d left it as two books it just would have been…” He said, “I know.” And then he had some other scripts that were being submitted and he said, “Maybe you should take a look at these.” And I looked at them and I talked to him and I said, “You know this is just taking Deadman and turning him into the Flash or something. It’s not a Deadman story.” He said, “You want to write it?” I said, “Yeah. I’d love to write it. At least it’ll be a Deadman story.” So that’s what I did. I started writing Deadman. You can’t really tell when you read the stories how much it re-focuses on Deadman, because I’d always kind of made it focus on Deadman through the art and the various things that happened, but it became even more re-focused on Deadman. People seemed to like that.

Stroud: It did pretty well there for quite some time although of course ultimately it got canceled.

NA: Well, it got canceled for very interesting reasons. Are you a historian?

Stroud: Oh, a little bit. Like I say, my focus is more the Silver Age than anything else.

NA: One of the interesting stories of the Silver Age is the advent of comic book shops. You’re aware of comic book stores?

An ad for Deadman featuring art from Neal Adams.

Strange Adventures (1950) #207. Cover by Neal Adams.

Deadman (1985) #1. Cover by Neal Adams.

Stroud: Right, instead of the twirling metal rack at the corner grocery.

NA: Yes. The twirling metal rack at the corner grocery was actually the magazine rack at the magazine distribution center or toy store or candy store where they had comic books. What was happening in those days was that the distribution of comic books and magazines was going way, way down because they had discovered this concept. Originally they had a concept, and this happened when I was a kid, where what they did was they had a concept of returns, like if they didn’t sell your magazines, they’d return them and then you’d try to redistribute them to various places or you’d try to work out some kind of deal, you know, give them to hospitals or whatever, but it was a big pain in the ass. You’re doing a magazine and you get these magazines returned to you, what do you do with them? Well, you take them to a warehouse and eventually you destroy them. So the distributor said, “Well, why don’t we destroy them?” “Well, how do we know that you’re telling us the truth, that you didn’t sell so many, because you could just keep the money?” (Laughter)

Stroud: Yeah. A valid question.

NA: So they said, “Well, why don’t we do this? We’ll slice the logo off the top, put them through a machine and we’ll just slice the logo, wrap them in rubber bands and we’ll send you those back.”

Stroud: Okay. Yeah, yeah, I’ve seen those.

NA: Sounds like a good idea. So they started to do that. Now in my neighborhood I would go to this toy shop that was on the way to Mark Twain Junior High in Coney Island, and there would be this toy shop and you could buy comic books, last month’s or the month’s before, comic books, for 3 cents and 2 cents and 5 cents. But the top, where the logo is, would be sliced off.

Stroud: Ah-h-h-h.

NA: The two cent ones, the slicer would go through 2 or 3 pages, so you’d really lose reading material, but if you just wanted to read the comic book you could sort of imagine what was there and pay 2 cents for it. Or 3 cents or 5 cents. The 5-cent ones, just the logo was stripped off. So this whole idea of keeping the distributor honest… (Laughter.)

Stroud: Wasn’t working.

NA: No. It didn’t work. Not only didn’t work, it didn’t work a lot. I used to trade comic books with kids with the tops cut off all the time. I don’t know if the comic book fans have those copies, but whatever the reasons and however the manipulations went, everybody sort of agreed that that wasn’t a great idea. But, then they came up with a worse idea. An idea so much worse that you can’t even conceive of it. When I tell it to you, you will say to yourself, “That can’t be. It’s not even possible.” They said, “Why don’t we have what is called an affidavit return? I will say that I destroyed 500 copies, and sign a piece of paper to that effect.” (Laughter)

Stroud: Ah. The old honor system.

NA: The honor system.

Stroud: With no honor.

NA: I will say that I threw them into the shredder. So now that I’ve said I’m throwing them into the shredder, what do I do with them? Because I’ve just said, “I’m throwing them into the shredder.” Now I can either throw them into the shredder, or make a buck. Hmmm. Difficult decision. For an honest man, a difficult decision. But you know magazine distributors, not exactly honest men, you’ve got those Playboy magazines, you know. Affidavit returns…I’ve got customers who will take those Playboy magazines and sell them easy to all the barber shops in town. So, at that time there were 440 local distributors. Why do I know that? I know everything. 440 local distributors around the country. Some of them have consolidated in recent years, but at that time it was about 440.

If you were an entrepreneurial young man, a teenager, or maybe a little bit older than a teenager, and you had your father’s station wagon, or van, not too many vans in those days, station wagon; you could drive up to the back of your local distributor, 440 of them; one in your area, and you could go to the back, and you could walk in the back, and there would be a table next to the door where the trucks loaded. There would be a table. And on the table would be Playboy magazines, Cosmo, tons of comic books, tons of comic books and you could buy them for, let’s say it was a ten cent comic book, let’s say a 15 cent comic book, you could buy them for 5 cents.

Challengers of the Unknown (1958) #74. Cover by Neal Adams.

Original pencils for a Challengers of the Unknown (1958) #74 splash page by Neal Adams.

The Witching Hour () #13. Cover by Neal Adams.

Stroud: Bargain basement.

NA: Bargain basement. Now there’s no way that you’re going to report as a distributor that you sold those comic books, because if you report that you sold them you’d have to sell them for 8 cents or 9 cents. If you sold them for 5 cents, nobody’s making any profit, so you just write them off as being destroyed. Shredded. So you had guys with station wagons all around the country who would go and do that; buy those comic books and they would go to their friends who were interested and then they would rent a motel room or a hotel room, like in the Penta Hotel in New York.

And they’d rent a room and they would invite all the comic book fans in the area that they have learned to know and love over the past years because they were all comic book fans and they did newsletters among one another and the announcement would go out that these comic books would be for sale at various prices in this hotel room. Guys would come up, drink a little punch, buy whatever comic books they wanted at whatever condition they wanted to buy them at. And some of them would go out and sell some of those. So all around the country, you’ve got these little get-togethers in motel rooms, in the local church, outside of school, blah, blah, blah, of people buying comic books from the back of the distributor for 5 cents apiece and selling them for 15 for 20 cents, sometimes they’d sell them for two bucks because they got some really nice stuff that you couldn’t get in your local distributors because your local distributors, your local store wasn’t even getting them.

Stroud: Oh, golly.

NA: Wasn’t even getting them. Those guys, all around the country, became your first comic book stores. You want to know where the guys who owned those comic book stores came from? Those are the guys with the vans. That would buy the books out of the back of the distributor, and sell them at the motel room. Those are the guys who became the comic book stores.

Stroud: Started their own sub-market.

NA: Well that’s how the direct sales market began. From those guys. One guy went into DC comics and said, “Look. Instead of you sending them to your distributor, telling you he only sold 40% of them, I’ll buy them from you direct, and I’ll pay you full price, no returns.” How could you lose? They went to Marvel and did the same thing. Once DC started to do it, Marvel started to do it. That became Phil Seuling and the direct sales market, the beginning of the direct sales market.

Stroud: Wow. Just an obvious, logical progression.

NA: Exactly. Now, put yourself in that historical position. Forget that the direct sales market has begun. Think of all those distributors around the country and all those guys pulling up in the vans. You’re gonna go in and you’re gonna buy comic books, only you’re gonna focus, to a certain degree, on comic books you can sell for two bucks or 50 cents rather than 15 cents.

So you’re going to get, let me see, Steranko’s Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D., Barry Smith’s Conan, Neal Adams’ Deadman, Green Lantern/Green Arrow. What books are you gonna buy? Batman, by Neal Adams. What books are you gonna buy? Sell to your friends. I go to a comic book convention now, I sign mint condition copies of Green Lantern/Green Arrow and Batman, bought by the box load out of the distributor. My good friend Carmine, “Gosh, Neal, I don’t know why Deadman isn’t selling better. I mean, you know, when you do a cover on another comic book it goes up 10 points, but you know your own comic books just aren’t doing that well.” (Laughter.)

Stroud: Just all that work in the shadows. Interesting…

NA: How much sense does it make that the most popular comic books out there didn’t do any better than the other comic books? Just pick the comic books at the time. The most popular comic books and the ones that everybody wanted to get, they didn’t do any better than any other comic books. There’s a reason. Some of them actually did worse. Nobody understood why. The reason they didn’t understand why is because nobody in the comic book business thought to investigate the distributors, and if they did, what could they do? Arms broken?

Stroud: Totally out of control at that point.

NA: Right. Now they could have asked for returns. It’s possible. The reason I know this is because when we did comic books we got into the distribution business, we didn’t get into the business, but we dealt with the distributors, and my daughter went around to the various distributors in our area, and they were only too delighted to show her the table in the back with this old shit. “Ah, yeah. This is the table where we sell shit. The guys come in; they just pick the stuff up.” “Oh, really?” (Laughter.)

Stroud: Good grief. That’s quite the story.

NA: We’re at a comic book convention when we were distributing, and we had some comic book store owner come over with a bunch of comic books to our table, and this is well into this whole idea, because that business didn’t discontinue. What happened was as time went on, as the comic book stores opened, what they would do is the comic book stores, let’s say they ordered a certain comic book and it did well. And they discovered that it did well by selling out. So what they’d do is they’d take their vans and go down to the local distributor and say, “Have you got any of these left?” Then they’d buy them for 5 cents or whatever amount the percentage was, and they’d take them back to their stores and sell them as if they were the direct market sales copies. Right?

So, what happened was certain comic book companies, and us included, we did things with our comic books. For example, we did a glow in the dark Cyber Rad and we distributed the glow-in-the-dark to the direct sales market, but the regular copy went to the retail market. One day my daughter is at a convention and we’re selling stuff and some comic book store, local retailer, comes up and says, “Why doesn’t this have the glow-in-the-dark? This is a rip-off.” My daughter looked at him and she said, “You got that from Diamond?” “Yeah.” “Well, you know we didn’t ship the glow-in-the-darks to the regular retail stores, we only shipped the glow-in-the-dark to the direct sales market. So are those direct sales market copies or are those from the local distributor?” “Uh…uh…I’ll go check.”

All-Star Western (1970) #5. Cover by Neal Adams.

Strange Adventures (1950) #218. Cover by Neal Adams.

House Of Secrets (1956) #85. Cover by Neal Adams.

Stroud: (Laughter.) Never to be seen again.

NA: Yeah, you go check. Schmuck. Thief.

Stroud: Nice try. Born at night, but not last night.

NA: Anyway, so if you want an explanation, and I believe Carmine is still confused about it.

Stroud: That could very well be.

NA: “How come they didn’t sell? They did so well.” Carmine did a speaking tour, went around the country and did like radio interviews on Green Lantern/Green Arrow. He was invited to all these places and, “Why aren’t the damn comic books selling?” “I don’t know.”

Stroud: That was quite a watershed event there, too, was it just mainly Denny’s work or was it pretty collaborative as far as the socially conscious effort?

NA: I would have to say that you have to give Denny total credit for the extremely socially conscious aspect of it. What had happened was that I was a big fan of Gil Kane and Gil had left DC Comics to do whatever he was doing, Blackmark or some stuff. So he was no longer going to be doing Green Lantern, which if you had interviewed Julie Schwartz at the time he would say, “Good-bye, good riddance, goddammit.” But essentially he knew that Gil made Green Lantern. So they started to hand out the books, the scripts to other people. Jack Sparling and people like that, and of course the stuff was terrible. So I went to Julie and I said, “Look, Julie, please, before you cancel the book let me do a couple of issues.” He said, “You wanna do Green Lantern?” And I said, “Yeah.” “Why? You’re out of your mind. The sales are diving down.” I said, “No, man, I really love the character and I love Gil Kane’s work. I’d like to do kind of a Gil Kane thing; I’d really love to do it.”

So I had done a kind of a revise of Green Arrow in the Brave and the Bold. They decided to pull Green Arrow and I thought, “Wow, shoot. The character’s kind of a nothing character, why don’t I turn him into something?” So, I had turned Green Arrow into a pretty good character in the Brave and the Bold, but there was nothing for him to do. Everybody was like; “Wow, he’s cool looking,” but they didn’t know what to do, so it occurred to Julie, why don’t we do Green Lantern and Green Arrow? Of course he mentioned it to me and I said, “Are you out of your mind?”

Stroud: (Laughter.) They’re both green.

NA: What is that? That’s not even funny. You’re out of your mind. He said, “Well, I’m thinking of maybe making it a continuing story with the two characters and I’ll call Denny O’Neil in. You’re working pretty good work with Denny.” I said, “Yeah that would be good.” So he called Denny in and essentially Denny, having been a reporter and also being very socially conscious, Denny was a bit of a radical at the time. They kind of asked me if I minded it going off in a little bit more meaningful direction and of course I said, “No, no, that sounds great. If I’m going to have to do two green guys, it doesn’t really matter where I’m going. Let’s get crazy.” So essentially all I gave was approval. Denny went off and started writing very, very socially conscious stories. He knew that I would carry them through. It’s sort of like a writer and director, you know if the director is going to do the job then you can basically focus on the story. So that’s what Denny did, he really focused on these stories and we did some pretty darn good stories, in my opinion, until we got to the drug thing.

Stroud: Yeah, I imagine the Comics Code kind of tripped that one up a bit.

NA: Not really. What happened was we were going along and Denny did a number of good issues. We attacked President Nixon and Vice President Spiro Agnew and that got a letter from the Governor of Florida telling us that if we ever do such a thing again he’s going to discontinue distribution of DC comics in Florida. Florida has managed to keep that reputation, even up to recent years. So we managed to ruffle some feathers along the way, but essentially nobody actually knew what we were doing until we were about into our third issue and then everybody liked it.

My good buddy Carmine will tell you he knew what was going on, but he had no idea. That was the good thing about it was that no one was paying any attention, so we actually got really into the meat of it before anybody kind of woke up, and the books were distributed, you know, you don’t distribute them the following week, so we were into our third or fourth issue by the time everybody goes, “Whoa! What’s going on here? This is like cool, or awful,” or whatever the hell they might have thought.

Stroud: You had a good roll on.

NA: Yeah. So we got into a number of issues, but we were starting to get into overpopulation by that point and I was getting a little antsy because, you know I don’t consider overpopulation to be what you call your “issue.” It’s a phenomenon and people have to deal with it, but you know if you have Americans getting vasectomies while Indians are having as many as 10 to 12 children in a family, this is not the solution to the problem.

All New Collectors Edition (1978) #C56. Superman Vs. Muhammad Ali cover by Neal Adams.

Batman from the comics meets Adam West. A commission by Neal Adams.

Stroud: Precisely.

NA: Not a good direction. So people who can afford it, not having kids, it’s just stupid. Anyway, so I was feeling, you know, we’re coming to the end of this run here, but you know what we haven’t done? We haven’t done anything on drugs. And it was a big issue and there had been kind of a thing over at DC comics where the state of New York came to DC comics and they wanted to do a drug comic book and Denny was asked about it and I was asked about it, so Denny did an outline and I did an outline of what kind of book it could be and they didn’t like our outlines (laughter) and we had taken a lot of time. Both Denny and I had gone to Phoenix houses and we had talked to the guys and you know the shit that you hear isn’t exactly the shit you hear from the guys who are really junkies. Very, very different. I was also the president of the local board of our drug addiction house in the Bronx.

Stroud: So you saw it all.

NA: I saw it all, had some experience and I was taking guys down from 42nd street with their noses running on their bellies and locking them away into our local, what was originally a nunnery and getting people in who were banging on the doors and it was just like…nuts. Anyway, I knew a lot about it.

So, because I had a lot of experience I had an awful lot of knowledge and things were not, you know, “Oh, just stop. Just tell people no.” That’s not the way it is when you have a kid coming home from school at night and his father comes home and he comes home, he’s got a load of homework to do and a load of things to do and he wants to enjoy himself and hang out with his friends but he can’t because he’s loaded down with homework and his dad comes home, kicks his shoes off, smokes a cigar, gets some booze and sits in front of the television and yet he’s treated like a king and this kid is treated like shit. A kid can get annoyed at that and perhaps unhappy and if he hasn’t got too much to go to, there’s a very good chance that he will go to drug addiction. I can’t imagine why…

Stroud: (Laughter.) Yeah, go figure.

NA: So the problem with society, both of us, Denny and I, realized was that we were not taking care of our kids and we were not giving them alternate things to do and we’re not rewarding them for their hard work and we weren’t doing much of anything. We were actually making potential addicts.

Stroud: Disengaged.

NA: Yeah. And they wanted us to do something about telling them to say ‘no’. This is like, “You’re bad.” No. We don’t think so. You’re bad, society, you’re screwed up and you’re making us bad, but we’re not that bad. So they weren’t happy with what we did, so they abandoned the project. So we’re going into this overpopulation thing with this Green Lantern/Green Arrow thing and I think, “We’ve got to do something on drug addiction,” but of course it’s against the Comic Code, so I went home and I did that first cover. You know, with Speedy?

Stroud: Yeah.

NA: In the foreground? I penciled it and I inked it and I put the lettering in and I brought it in and I gave it to Julie Schwartz and his hand grabbed it very briefly and then he dropped it on the desk as if it were on fire. He said, “We can’t do this.” I said, “Well, we ought to.” He said, “You know we can’t do this. It’s against everything.” I said, “Well, this is where we’re going. This is what we ought to be doing.” So he said, “You’re out of your mind. Once again, you’re being a pain in the ass.” So I took it into Carmine. Carmine didn’t know what to make of it. I took it into the Kinney people, who were now running DC comics and were sort of used to this and of course they dropped it like a hot potato.

I said, “You know guys this is where we ought to be going with this.” “Oh, no, Neal, please, just go and work. Leave us alone. You can’t do this.” And of course Julie had a twinkle in his eye, but still he knew it was bullshit, it wasn’t going to happen. He said, “Why did you finish the cover?” I said, “Well, because it’s going to get printed.” “No, this will never get printed.” Anyway, I make a visit over to Marvel comics a week or so later and somebody comes over to me, probably Roy [Thomas] or somebody, I don’t know and says, “You know what Stan’s [Lee] doing?” I said, “What?” He says, “He had this guy, this drug addict popping pills and he like walks off a roof.” I said, “Stan had a guy popping pills and he walks off a roof? That’s kind of a unique situation.” (Laughter.) “I don’t exactly know where you’re going to find that, you know I don’t know who’s going to be walking off a roof.” “Well, you know Stan read some kind of article about a guy who went off a roof.” “Oh, okay. Sure. All right. Whatever.” And he said, “So we did it and we sent it over to the Comics Code and the Comics Code rejected it, they said he has to change it.” So I said, “Well, what’s Stan gonna do?” “He’s not gonna change it.” “You’re kidding.” He says, “No. Not gonna change it. We’re just gonna send it out, it’s ready to go out. We’re sending it out. It’s going to be on the stands next week. Week after next.” “Really? No shit. What about the Comics Code seal?” “Not gonna put the Comics Code seal on it.” “Really?”

Stroud: You can do that?

NA: So sure enough, he sends it out and I go over to Marvel comics since I heard it was out and I go over and I say, “What happened?” He said, “Nobody said anything.” “Nobody said anything?” “Nobody even noticed that the seal wasn’t on there.” “No shit. Nobody even noticed?”

Stroud: What do we do now, Batman?

NA: What do we do now? So I go back to DC, you know, and now that word had gotten out, oh shit. Now try to imagine DC, they’ve got this cover, right? Could have scooped Stan with something real and solid. They screwed up. So within a day or two they call a meeting of the Comics Code Authority. Remember the Comics Code Authority is bought for and paid for by the comic book companies. It doesn’t exist independently. It’s a self-regulating organization. So DC Comics calls Marvel, they call Archie, they go and have this emergency meeting. “We’re going to revise the Comics Code!” Okay, within a week they revised the code and within a week and a half they tell me and Denny to go ahead with the story. (Laughter.)

Green Lantern (1960) #89. Cover by Neal Adams.

A panel from Green Lantern (1960) #89. Art by Neal Adams.

Batman/Superman () #29 Neal Adams Variant.

Stroud: Just that easy.

NA: Just that easy.

Stroud: Oh, too funny.

NA: Well, it took the cooperation of quite a few people, but there you go. That’s how it happened.

Stroud: Incredible.

NA: So Stan is responsible for us being able to do that drug story, when you get right down to it. Thank you, Stan. I’m popping a pill, walking off a roof.

Stroud: About as unrealistic as possible, but nonetheless…broke down the door.

NA: Incredible. Stan was always kind of like innocently naïve. “I wonder what would happen if we just threw this out.” Not, “Oh, the shit hit the fan and we’re in trouble now.” Just, “Oh.” Stan in his own way is just wonderful. He’s like the world’s innocent.

Stroud: Just go for forgiveness rather than permission and see what happens?

NA: I guess. I don’t even understand it, but still he won the day. He won the day for us. Incredible. Stan, thank you. How do you say thank you? Thank you, Stan, for having a guy popping pills and walking off a roof.

Stroud: Excelsior!

NA: Excelsior.

Stroud: Now you went over to Marvel shortly thereafter, did you not? Did you prefer the Marvel Method for your kind of work or did it make any difference?

NA: Well, I’ll tell you the sequence of events. I had done a Deadman story and in the Deadman story I did some kind of special effects. I did one thing that takes up the page and it’s kind of a double image. So I was doing this optical illusion because Deadman was going into this mysterious, hell-like place or heaven-like place, or whatever. To find Vishnu or whoever. So I’m doing these optical illusions and there’s this one panel I did at the bottom where I have the steam rising up from below going past Deadman. And if you take the comic book and you hold it at an angle, so you look like down the comic book at a very steep angle, that steam that rises up coalesces into letters. It squishes down and then you see letters.

A panel from Strange Adventures #215. Neal Adams creates a Jim Steranko effect.

The Spectre (1967) #4. Cover by Neal Adams.

A panel from The Spectre. Art by Neal Adams.

Stroud: Okay, sure. Sure. Like the old 60’s posters for rock bands and stuff.

NA: Right. It shrinks down, so if you look at it from the bottom it says, “Hey, a Jim Steranko effect.”

(Sustained laughter.)

Stroud: Subliminal messages.

NA: Because Jim was over there with op effects and doing all kinds of things, so I thought, “I’ll do this.” Cute little thing. Anyway, the thing comes out and a week or two afterward Jim Steranko comes over to DC comics, seeks me out, shakes my hand and says, “Hey, that was cool.” I said, “Thanks.” And so we got to talking and I asked him about what was going on at Marvel and he said “Well, they have this way of doing it. Stan does so many books that he just lets you do the story and you hand in the pages and you write the story on the side or with notes as to what takes place and Stan writes the dialogue.” “That’s pretty interesting. You get scripts over here.” He said, “It’s a pretty good way to work because basically you’re in control of the story. You decide what the story is and Stan puts in the words.” “Huh.”

That was known in those days as the Marvel Method. Because there was Stan, you could just do so many books. At that time they were bringing in Roy. So anyway, I thought, you know, I would like to do something like that for a couple of issues. I would enjoy that. Hmmmm. So I thought about it for a couple of weeks. And I went over. I called Stan and I said I’d like to come over and talk, I’m interested in doing something. Not that things were slow, it’s just, I just do things like that. Also some other things were happening at that time that were bothering me. For example when artists would go back and forth between the companies, they would sign different names.

Stroud: Oh, yeah, aliases. I’d heard about that.

NA: Aliases. Yes. Mickey Dimeo was, uh, I don’t know who the hell he was.

Stroud: Was that [Mike] Esposito?

NA: I think so, somebody like that. Anyway, so they would sign different names, because they didn’t want the companies to know. Like, you know, you’re not gonna know. So they were doing it and it was, “Oh, no, Stan wouldn’t like that.” “Why don’t you sign your name?” “Oh, I couldn’t.” So they worked under aliases and I thought it was stupid and also not good for the freelancers. Very bad. So, I thought I’d kill two birds with one stone. So I went over and I talked to Stan and I said, “I’d like to do a Marvel book in the Marvel style, you know where I do the book and the dialogue gets put in.” Stan said, “What book do you want do?” I said, “Well, what do you mean?” He said, “Well, you can do any book you want.” I said, “Stan, that’s very nice. Why are you saying that?” He said, “I’m saying it because the guys around here are saying that the only book they’re reading from DC comics is Deadman.” (Laughter.)

Stroud: Aha! Your reputation precedes you.

NA: “I see. Okay.” So I said, “You don’t mean any book.” He said, “You can have any book you want. You can have Fantastic Four, you can have Spider-Man, you can have anything.”

Stroud: Geez, carte blanche.

NA: Yes. So I said, “Okay. What’s your worst selling title?” He said, “The worst selling title is X-Men. We’re going to cancel it in two issues.” (pause) Let that sink in. ‘The worst selling title is X-Men. We’re going to cancel it in two issues.’

Stroud: Unfathomable.

NA: Well, it wasn’t so much if you look at the books at the time. Barry Smith, one of his earliest jobs at Marvel was an X-Men book and when I say early job, I mean crap. (Laughter.) And they really weren’t very good. If you read them, they’re not good. So I said, “I tell you what. I’d like to do X-Men.” He said, “But I told you we’re going to cancel it in two issues.” I said, “Well, that’s fine.” He said, “Why do you want to do X-Men?” I said, “Well, if I do X-Men and I work in the Marvel style, you’re pretty much not going to pay too much attention to what I do, right?” He said, “That’s true.” I said, “Well, then, I’d like to do that.”

X-Men (1963) #56. Cover by Neal Adams.

X-Men (1963) #56. Cover by Neal Adams.

X-Men (1963) #56. Cover by Neal Adams.

Stroud: Gonna have some fun here.

NA: I’ll have some fun. He said, “I’ll tell you what. I’ll make a deal with you. You do X-Men until we cancel it and then you do a really important book, like The Avengers.” Now in those days The Avengers was a big deal. I don’t know about today. Today it’s coming back up again. It’s not as funny a story as it was 10 years ago. (Laughter.)

Stroud: Following in Kirby’s footsteps there, so…hallowed ground.

NA: So he says, “Then you’ll do Avengers.” So I said, “Okay, that sounds like a deal.” So I did 10 books of the X-Men, which you see reprinted all the time. Then they canceled the book. (Laughter.) Why did they cancel the book? Because sales weren’t so good. (Laughter.)

Stroud: Yes, of course.

NA: Let me see, you have a mint condition copy of the X-Men? (Laughter.) How did you get that? “I don’t know. Some guy had a box of them.”

Stroud: Fell off the truck.

NA: A box of them? I must have signed more than they actually sold over the years. I sign them all the time.

Stroud: I believe it.

NA: Where do they come from? Well, we know where they came from. Back of the warehouse. Those X-Men books, they did pretty good. So anyway, what happened was they cancel the book and the fans jaws drop. “What the hell’s going on?” And of course the fans wrote in letters and the interesting thing that happened was fans wrote in letters, they wanted to see the X-Men again, so they basically started to do reprints and then they started to do it again, but every artist, every new artist that came to Marvel comics from that point on wanted to do X-Men. Dave Cockrum. John Byrne. All those guys, well not all, but the next group of guys, all they wanted to do was the X-Men. That was it.

Stroud: That or nothing, huh?

NA: Yep. And if you look at the X-Men runs on the various guys, what you’ll see, interestingly enough, is that those guys have all gone through the basic stories that I did when I did those 10 issues. They all do Sentinels, they all go into the Forbidden Land, they all have Ka-Zar, one story with Ka-Zar, one story with dinosaurs. Essentially they just travel through that same sequence of stories to give their take on another version of those stories. Almost every guy. Just to go ahead and do it. “I want a shot at doing that. Sauron, I wanna do him.” Sauron suddenly shows up. New artist, there’s Sauron.

Stroud: Just like that.

NA: It’s incredible. Anyway, that’s what happened.

X-Men (1963) #63. Cover by Neal Adams.

Fear (1970) #11. Cover by Neal Adams.

Marvel Preview (1975) #1. Cover by Neal Adams.

Stroud: Oh, I love it. It seems like you really blazed a trail as far as the more realistic style. Prior to your arrival the only one I can think of offhand is Murphy Anderson, but following you it seems like you’ve got Jim Aparo and Mike Grell and so forth. Were they aping you do you think or was it just the new wave?

NA: (Laughter.) What do you think?

Stroud: It was interesting to me that Grell did Green Lantern…

NA: “Anybody with a beard. Anybody with a beard. Anybody with a blonde beard. (Laughter.) In fact, I’ll grow a beard. I’m growing a beard.” Hey, listen, shit happens, you know? To be perfectly honest, between you, me and the fencepost, I don’t feel, you know, guys aping my style was the contribution. I think the contribution, if anything, was the realization that somebody could be a good artist and do comic books. There’s nothing wrong with the idea. There’s nothing incompatible with being a good artist and doing comic books.

That essentially was the message and it’s the most lasting message. I mean, you know, you’re going to have guys that will ape your style. Only one or two of them were really any good, I mean Bill Sienkiewicz, who managed to go on past that style and other people who possibly went beyond it have made greater contributions than the guys who aped the style, but it wasn’t that so much as this idea that here were comic books that were being sold to college students, I mean you talk about Green Lantern/Green Arrow and even the Batman, even the X-Men, they went to colleges.

They sold very well in colleges. When I say very well, of course off the back of the warehouse, my fans, all my fans wrote with a typewriter. They didn’t write on grocery bags with crayons. They were intelligent, they were well read, they had something to say and the people who followed in the industry, we have a much more intelligent, talented field. But the only way to get something like that is if somebody says, “Hey, yeah. I could choose to do anything I wanted to do. I choose to do comic books.”

Stroud: Legitimacy as an art form.

NA: Exactly…well, I wouldn’t give it an art form status. I’m kind of hoping to duck that one, but to give it a pop culture status that is as good as music, is as good as dance, is as good as film making on a high level quality, we’re not looking to make art, but we are looking to please people and to do good art while we do it. Mixing good art in there is not a bad thing as long as you don’t get too hoity-toity.

Stroud: I think that’s a very accurate summation. They were also showing a lot of artists the door about the time you showed up. Was that in any way related?

NA: Who were they showing the door to?

Stroud: Oh, I was thinking of George Papp and Shelly Moldoff.

NA: Well Shelly Moldoff hadn’t worked for comics in a very long time.

Stroud: I was under the impression he was still at it up until the late 60’s, perhaps my information is wrong.

NA: I don’t think so.

Stroud: The Wayne Boring’s…

NA: I think Wayne Boring was not part of it into the 60’s. He certainly wasn’t there when I was coming in. There was Curt Swan. Curt Swan was the classic Superman artist. Wayne Boring was not there any longer. In fact, I wondered about Wayne Boring. What was Wayne Boring doing at that time, do you have any idea?

Detective Comics (1937) #389. Cover by Neal Adams.

Batman (1940) #222 original cover pencils by Neal Adams.

Batman (1940) #222. Cover by Neal Adams.

Stroud: I don’t know.

NA: Because I can’t imagine that they would let go of anybody at that time. They needed everybody that was available.

Stroud: That’s kind of what I thought. It kind of threw me.

NA: I think you’d have to talk to those people to find out, because you know if you’re in this industry for a long time and then you discover that actually there is somebody else out there who will actually pay you money to draw and probably pay you more than these comic book publishers, you tend to want to do that. To be perfectly honest doing comic books to a certain extent in the 60’s was like a charity. I would do story boards for advertising agencies and I would get paid the same for a story board frame as I would get paid for a page of comic book art.

Stroud: That’s pretty consistent with what Joe Giella was telling me when he was doing advertising type work. He said the money was much, much better.

NA: No comparison and if you were able to pick up enough work…and what happened with various people was…let’s say you’re in a city, let’s say you’re in Detroit and you’re mailing your comic book pages in if you’re lucky enough to be in a situation like that. Suddenly in Detroit it’s a smaller pond than say, New York, so the competition isn’t quite as stiff so somebody like Wayne Boring, and I’m not saying this happened to Wayne Boring, but somebody who has reasonable ability suddenly finds themselves in an advertising agency and being paid a reasonable rate to do a story board frame, what he would be paid to do a comic book page and suddenly somebody from down the hall has work for him and suddenly from this other agency and they’re letting him do freelance work at night, suddenly he’s tripled or quadrupled his income. Why would he want to do comic books? Why would he want to be bored to that extent whereas these people are grateful and they’re saying, “Thanks. Gee that’s great. You were able to knock it out so fast. I really appreciate it.” It’s a different world. A totally different world.

Stroud: Sure, sure. Instead of a Kanigher or a Weisinger, saying…

(Laughter.)

Stroud: “What’s wrong with you? This sucks.”

NA: There were editors who were, in fact, ogres. I never had any problem with any of them, but other people, I know did. Sometimes I’d have to take them aside and say, “Why don’t you take it easy on this guy? He’s got to make a living. He’s not going to change if you get mad at him overnight or something.”

Stroud: Not going to cause a radical shift in what you think it should be.

NA: I got along with Kanigher just fine. I got along fine with Weisinger.

Stroud: It sounds like you’re one of the few.

NA: Well, I’m not really the kind of person you want to get angry. ‘Cause I really just have a positive attitude about everything and to me if somebody crawls up my back it’s like a surprise, it’s “What are you crawling up my back for?” I’ll give you an example. I’ll give you my Kanigher story. I’ll give you my Kanigher story and I’ll give you my Weisinger story.

The Shadow fights Shiwan Khan. A commission by Neal Adams.

A Deadman sketch by Neal Adams.

A Conan print with a Deadman Sketch on it by Neal Adams.

Stroud: Okay.

NA: My Kanigher story: I’m in the room with Bob. I give him my second war story. I did a series of war stories. First war story went just fine. Handed it in, looked at it, that’s it. Brought in my second war story. He starts to look at it, maybe he’s got a little more time, I don’t know. A little grumpy. He starts to correct my art. He starts to criticize my art. I said, “Hold on Bob. Just hold on a second.” So I got up out of the chair, and I closed the door to the room. I said, “I’ll tell you what we’ll do. We’ll have an arrangement between us.” Now you know when you close the door on somebody they kind of go, “Why is he doing that?”

(Laughter.)

NA: The thought doesn’t necessarily occur to somebody that you’re going to hit them, but if you close the door, nobody knows. I wasn’t going to hit him, but I said, “Now let’s be real quiet about this, because I don’t want anybody to think you raised your voice at me. You’re the writer. I’m the artist. I’m not gonna criticize your writing, you don’t criticize my drawing.”

Stroud: Stay in your lane.

NA: “Sound like a deal?” He draws his head back, he goes, “Yeah, I guess that’s okay.” I said, “Fine.” Then I opened the door and we went on. That was the last harsh word, or even partially harsh word I ever heard from Kanigher. From that point on, we were friends. He’d come and tell me about his conquests, he’d tell me about the girl he laid up in the Himalayas or whatever the hell it is and I was a friend. He’d bitch to me about other people and I’d try to calm him down, but essentially we got along easy. I know that Joe Kubert got along with Bob Kanigher, but Joe Kubert’s the kind of guy that doesn’t take any shit from anybody. So I think Kanigher was one of those guys that would challenge you unless you got up on your hind legs and suddenly, then you’re okay. That’s the way it was with Bob. That’s my Bob Kanigher story. Now, my Mort Weisinger story. (Chuckle.) Mort Weisinger was always nasty to everybody.

Stroud: That’s what I hear.

NA: Always, always nasty. And Carmine wanted me to do covers for Mort Weisinger. Mort Weisinger had Curt Swan. Now, between you, me and the fencepost, if I had Curt Swan that would be enough for me, and it was enough for Weisinger, but Carmine kept on him, about “Have Neal do a Superman cover.” And Weisinger is giving me these glowering looks like somehow I’m part of this…

Stroud: Conspiracy.

NA: Yeah, or whatever it is, so finally Carmine says, “You ought to talk to Mort; you know you ought to do covers for Mort.” So finally I walk into Mort’s office and I said, “Mort, I just want to talk to you for a minute.” “What?” “Carmine wants me to do covers for you.” He said, “I don’t want it.” I said, “I understand that. I’ve got it, totally, and I don’t disagree with you, but to satisfy Carmine, why don’t we do this. You give me one cover to do, I do it, you don’t like it, you don’t have to use it, you don’t like it, you never use me again, we forget about it, but at least we’re satisfying Carmine.” He said, “Okay.” “So, one shot, one cover, that’s it. That’s the end of it.” “Okay.” He says, “Fine.”

So he gave me a cover to do. After I did the cover, suddenly, “Hey, we’ve got to do some more covers.” (Laughter.) Suddenly Mort wants more covers. Anyway, now it’s a reasonably friendly situation with Mort. So one day…now I’m working quite well with Mort, but it’s a private conversation, slightly poignant conversation. I go into Mort’s office, Mort has just yelled at somebody on the phone. I said, “Mort, you know, between you and me, you know, you treat an awful lot of people bad. You really ought not to do that and I don’t understand. What’s the problem?” And he gets real quiet. He looks at me, and he says, “Look, I’m going to tell you something. Never repeat it.” Now of course I’m repeating it. He says, “If you got up in the morning, and you went to the mirror to shave, you saw this face looking back at you, would you be a happy man?” Oh. And I thought, “No. That’s really sad.”

Stroud: Quite an insight.

NA: That is really sad. So, I understood Mort. I didn’t like the idea that he treated people bad, but to be perfectly honest, you know, that’s a hell of a thing to look at in the morning.

Stroud: Yeah, that would start your day off on a grim note, no question. That’s very interesting.

NA: So there you go. So I got along with him fine, you know, to me they were just guys. I never had trouble with any of them.

Stroud: Good for you. Was there anyone you preferred interpreting penciling or so forth?

NA: You mean as far as an inker is concerned?

Batman punches Two-Face. Art by Neal Adams.

Joe Kubert: Legacies. Art by Neal Adams.

Creepy (1964) #14. Curse Of The Vampire pg. 1, art by Neal Adams.

Stroud: I’m sorry, yes.

NA: Oh. I prefer Neal Adams. I think I’m one of the best inkers around. I know that sounds egotistical, but when I did the Ben Casey strip I did it for 3-1/2 years and I based my inking on the best inkers in the field and I learned skills that other people didn’t learn. I trained under, when I was in high school at night I did animation for a guy named Fred Ang, who did animation for a Japanese animator and he could handle a brush like no American and he taught me how to use a brush and when I look at Americans ink with a brush it seems to me that they’re like gorillas holding a brush. The man taught me and I learned from Stan Drake how to handle the most sensitive pen that there is out there. If you hand a 290 pen point to any typical inker all they’ll make is a blob on a piece of paper, so I learned an awful lot about inking.

The best inker outside of myself at DC was Dick Giordano. The best inker for me at Marvel at that time was Tom Palmer; Tom Palmer continues as a terrific inker, but neither one of them, I mean if you look at the work of them over my stuff you see a total opposite of style. One very rough and very slashy and one very tight and very controlled and mine falls somewhere in between, but it’s more a kind of a classical ink style that you would get from Charles Andy Gibson or the Japanese brush painters or whatever. So my stuff is better served by myself. Nowadays there are better inkers around. I mean since then…you have to remember that we worked at a very, very difficult time where people were slashing and hacking at stuff like crazy. Now you have inkers that actually know how to ink very well and they’re willing to do the job. I’m working on a Batman series now and I have to think about, “Do I want to have some other people ink this stuff?” and there are people who, in my view, are tremendously worthy inkers that I’d like to give a try to, and probably will.

Stroud: Wow. That’s quite an endorsement.

NA: Well, things have changed. Boy, it’s become very, very different. There’s a half a dozen inkers that I would trust with a page of mine that I think I’m gonna get something close to what I’m able to do and that’s saying a lot, I gotta tell you.

Stroud: Do you think some of it is the time constraints aren’t quite what they used to be on these special projects?

NA: Oh, yeah. Time constraints are practically nothing. There are people who have work out now, but there are guys who will take 2, 3 days on a page and not think anything of it, because they know down the line they’re going to get royalties or their page rate is good or whatever and they’re also competing with a lot of very good people. The drive of competition in the comic book business has become a drive of quality and ability to sell books. So the link between quality and selling books is very, very firm these days.

Stroud: So it’s no longer a quantity game so much.

NA: No. And if you have people out there who are turning out less work and getting more money you have to think that that’s possibly the future and not cranking out pages. The day of Vinnie Colletta has gone.

Stroud: May it rest in peace.

NA: I’ve seen Vinnie destroy more pages than any five artists have drawn. My favorite quote from Vinnie Colletta is “Do you want a good inking job or do you want it on Monday?” The answer I’ve heard from editors is, “I want it on Monday.”

Stroud: I believe it. I’m reminded of one of my co-workers touting how women can multi-task and so forth, but that’s beyond you men, and so forth and I said, “Well, here’s my theory. Do you want something done quick or do you want something done well? Do you want several things done poorly or one thing done well?” That’s the way I work anyway.

NA: There you go. I wouldn’t necessarily equate it to women, just people who just don’t care.

Stroud: Yes, indeed.

NA: Because Vinnie wasn’t as much a woman as he was a man. (Laughter.) We didn’t have too many women in comic books as I think of it.

Batman (1940) #237. Cover by Neal Adams.

A Deadman sketch done by Neal Adams.

Batman (1940) #251. Cover by Neal Adams.

Stroud: No, not at all.

NA: The ones who were there were of a true quality and there’s the dichotomy. The women in comic books were…and they’re still alive, are tremendously quality oriented. Marie Severin and Ramona Fradon. One of my favorite artist’s. I never had any idea she was a woman. I had no idea. She used to do the Aquaman comic books, the back-up Aquaman comic books.

Stroud: Right and Metamorpho.

NA: Yep. Metamorpho.

Stroud: At least for a little while.

NA: And from her you get John Byrne and other people who work in a very similar style. She’s actually much aped even though people don’t necessarily recognize it or admit it. When you look at her work and you look at Alan Davis and John Byrne, people that you might say imitated my stuff, actually. There’s a tremendous influence, in every era, of Ramona Fradon. A tremendously good artist. She’s one of my heroes.

Stroud: So obviously you haven’t completely left comic books behind, but I understand you do a lot of story boards for movies and so forth, is that correct?

NA: Nothing for movies. It doesn’t pay well enough. I do advertising story boards and I do some designs for film, but not a lot, but here and there I’ll hit something. If you’re a designer for movies it’s different than doing story boards. Story boards, you turn out a ton of stuff and you turn it out very fast and you sort of work at it by the gallon.

Stroud: Just scratching it out, huh?

NA: If you ever see story boards from film you are often amazed at how scritchy scratchy they are and how quickly they’re done, but they get across the idea. They get paid well by the week if you get two, three, four thousand dollars a week, but you’re expected to turn out a tremendous amount of work and I can’t dedicate myself to boards for that reason. What I’ll do is I’ll do story board designs for amusement park rides, like the Terminator T2 3-D ride or the Spider-Man ride, stuff like that. If you go to my site (www.nealadams.com) you’ll see a lot of the stuff that I do. You won’t see any movie stuff really.

Stroud: Tell me one thing people would be surprised to know about Neal Adams.

NA: I’m not the pain in the ass they say I am.

Stroud: Ah-ha. Okay.