An Interview With Steve Skeates - Prolific Pontifications From A Worldly Wordsmith

/Written by Bryan Stroud

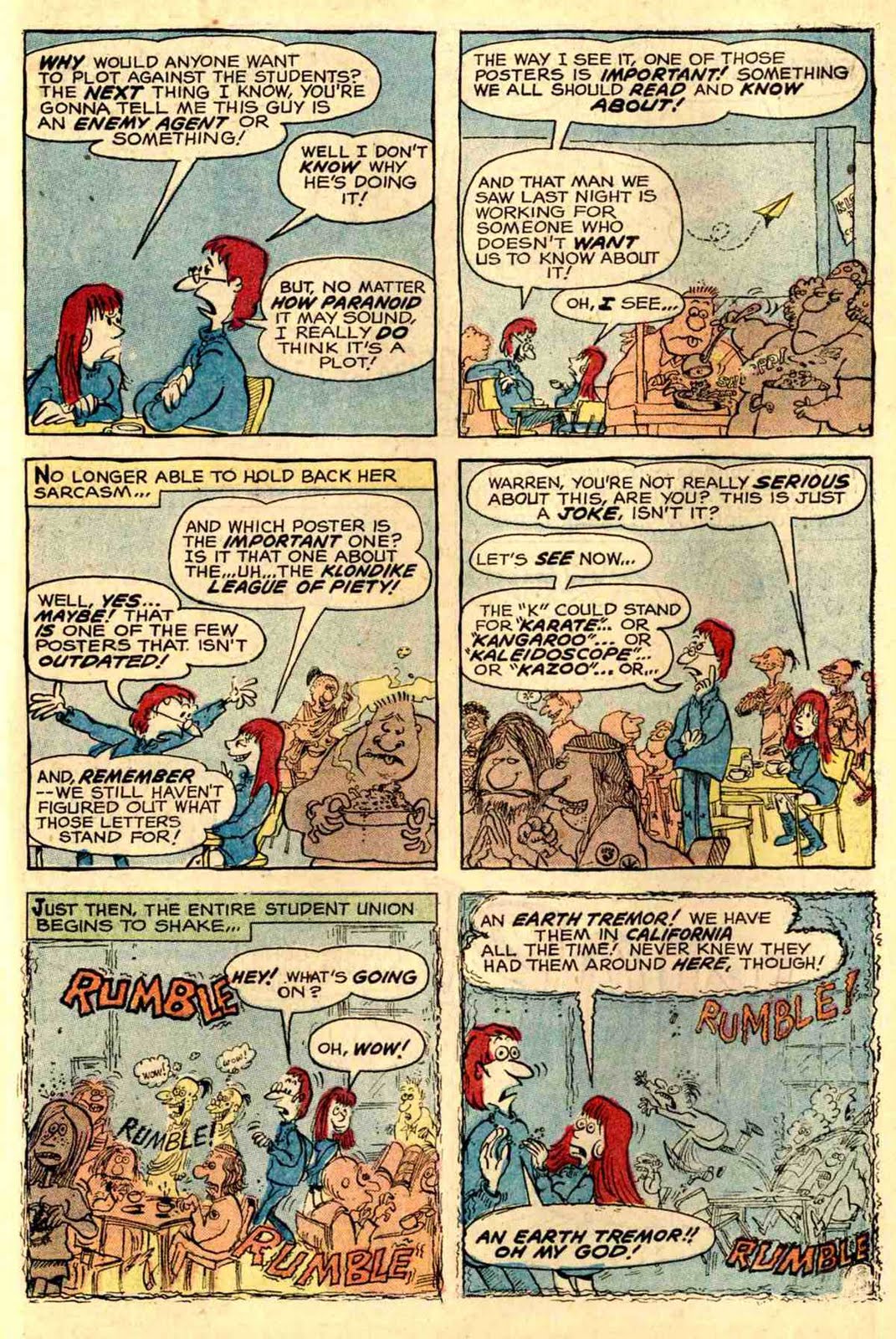

Steve Skeates in 2009.

Steve Skeates (born January 29, 1943) is an American comic book creator known for his work on such titles as Aquaman, Hawk and Dove, T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents, and Plop! Starting his career writing comics in 1965, Steve would go on to work for most of the major comic publishing houses in his time including: Marvel, Tower, Charlton, DC, Gold Key, Red Circle, Archie, and Warren Publishing. Though he is most often thought of in connection to his superhero stories (or his early westerns), Skeates also wrote horror stories for several different companies as well. His stories "The Poster Plague" (from House of Mystery #202) & "The Gourmet" (from Plop! #1) earned him 3 Shazam Awards and a Warren Award in 1972 & '73. In July 2012, Mr. Skeates received the Bill Finger Award for Excellence in Comic Book Writing.

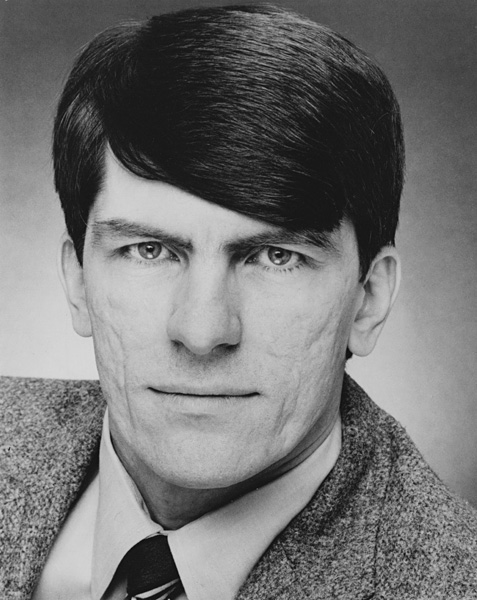

Denny O'Neil, Steve Skeates, & Dick Giordano at a convention in the '60s.

Steve Skeates was a writer I wasn't all that familiar with, though I was aware of his awards and the work he'd done on Aquaman in particular. He's graciously helped me on a couple of my Back Issue assignments since, both with Aquaman anecdotes and valuable information on his Plastic Man run. Steve is always friendly, helpful and seldom at a loss for words.

This interview originally took place via email on June 5, 2009.

T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents (1965) #4, featuring stories written by Steve Skeates.

Bryan Stroud: I've found there are numerous interesting paths to becoming a writer. What's your "origin?"

Steve Skeates: "A dreamer" is how my parents tended to describe me. The way I seemed to prefer to play by myself rather than interacting with other children. The manner in which while in the midst of one chore or another (like raking, a continual horror, cleaning up after what, even as a kid, I referred to as "the dirtiest tree in existence," the Catalpa, an ugly monstrosity that was forever dropping something or other all over the lawn; during one season it'd be large white flowers so malodorous that one's stomach would start churning within but a few moments of raking; at another time it'd be long cigar-shaped seed pods that were particularly adept at avoiding the effects of the rake, while of course in the Fall, looking not unlike an avalanche of pukey-green elephant ears, mounds of large ugly leaves would be everywhere; it was only somehow during the winter when in fact I'd be busy anyway, busy shoveling snow, that this evil entity would refrain from providing me with one or another of something or other decidedly off-putting that I had to dispose of, but to get back to what would happen even as I was doing so) I'd suddenly space out, stop working and go all glassy-eyed as abruptly I'd obviously get lost within the recesses of my mind -- not particularly dark recesses, not back when I was a kid, though only too soon (thanks to Val Lewton and William M. Gaines, amongst others) such as that would become a significant aspect of the inner-workings of this particular correspondent

Anyway, was my suddenly obviously being somewhere other than where in fact I was actually standing an indication that I was somehow an intellectual? Or was it conversely that I was much more autistic than the artistic that I (to this day) tend to conclude as being the exact nature of where it was I was at? I suppose, being totally logical, my reaction to both of those inquiries should be a resounding "Nah!" It was instead merely just as my parents had said it was – I was a dreamer! And often those dreams of mine would have a definite silly aspect to them! Like my wanting to become a writer -- a rather romantic notion especially in that it made the scene despite the easily discernable reality that I was far from being particularly adept at reading! I was (as a matter of fact) one of the world's slowest readers and that combined with the aforementioned spacey-ness I possessed would often mean that by the time I reached the end of a not even particularly long sentence I'd have long since forgotten what had been said at the beginning of the darn thing!

Star*Reach (1974) #1, featuring a story written by Steve Skeates.

To elaborate, were there among the questions that comprise this very interview one concerning the comic book or comic strip character I most closely identify with, my answer (at least at this particular point) would undoubtedly be Albert (the alligator in Walt Kelly's Pogo) who fancied himself a writer even though he didn't know how to read. He was forever typing something up, then asking Pogo to read it to him so he could find out what he had written. As a kid I enjoyed the utter silliness of all of this, whereas these days, as I glance backwards, I see it more as but a slight exaggeration of my own youthful plight. Obviously, then, the big question is, why would someone as utterly ill-suited as all of that ever want to become a writer? Had I at too early an age seen the movie My Dear Secretary (a definite favorite of mine) featuring Kirk Douglas as the fictional iconic irresponsible fun-loving best-selling romantic novelist Owen Waterbury? Quite likely! In any event, by the time I got to junior high and especially while in high school itself, I was already at least masquerading as an intellectual, bookish, hanging out at the local library, searching for some particular form of literature (if it even existed) that I could understand and follow well enough to perhaps even one day be able to write! What I found was humor! Blissfully short pieces by the likes of James Thurber, Wolcott Gibbs, Frank Sullivan, Donald Ogden Stewart, S.J. Perelman, Ira Wallach, and the great Robert Benchley. Parody, satire, cynical observations – nothing of all that much depth, yet entities just snarky enough to appeal to a dreamy loner's disappointment with reality, a potential Utopian's overly critical nature. And, although Perelman would often offer long hulking sentences which I'd get totally lost within, most of the others had a tendency toward simplicity, toward getting straight to the point, mainly due to the fact, I easily surmised, that confusion is hardly helpful when what one is doing is setting up for a joke. I read as much of this stuff as I could, perused them over and over again, analyzed them, got into exactly how they worked, and then finally noticed the dates on most of them, and, with a bit more research, realized that humor-writing was basically and rapidly becoming a thing of the past, a twenties and thirties and forties phenomenon that in the fifties was being done in by that new one-eyed monster that was taking up space in everyone's living room and by the fact that the American public (traditionally far removed from any sort of intellectualism to begin with and damn proud of it too) preferred watching Milton Berle to trying to sound out the words in even the simplest of laugh-inducing literature. In other words, to employ a familiar phrase of those times, I had been born too late.

Abbott & Costello (1968) #1, featuring stories written by Steve Skeates.

And so it was that I abandoned those dreams in which I in some beautiful future became a popular American humorist and fell back on my other forte, the fact that I had been rather a math whiz in both grade school and high school. Thus, in 1961, I entered Alfred University as a mathematics major! It wasn't long, though, before the collegiate scene itself (fraternity parties, available co-eds, all the booze, etc.) began to take its toll, especially for someone carrying such a heavy load of courses within such an exacting field as math! I was on the cusp of flunking out, but then I remembered how in high school, though I was such a slow reader, too slow to ever finish any of my reading assignments, I was able (at least in English class) to fake it enough to even get high grades! Perhaps I could do the same thing in college!! So, I became an English major, something I probably should have done from the git-go, considering my dream and all, although now I had no idea what I was gonna do once I hopefully got my degree! Most of the other Alfredian English majors were on the road to becoming high school teachers, but I certainly didn't want to go that route! Then, suddenly, down at the pool hall where they sold the more lurid magazines, there was an influx of comic books featuring such heroes as Spider-Man, the Fantastic Four, and Iron Man, all written by someone named Stan Lee, who possessed a nifty over-the-top style and was able to infuse his stories with lots of comedy, and, since comics had pictures which made them easier to read than straight prose, I saw this as yet another something that I might be able to do! Therefore, I wrote to Marvel Comics, asking about employment possibilities (on a whim constructing my letter as though it were a bunch of comic book captions) and (believe it or not) received a phone call from Stan Lee himself, offering me the position of assistant editor! Truth be told, I didn't last long in that position, my incompetence causing me to almost immediately get demoted to being a western writer, while Roy Thomas was called in to take my place as assistant editor! But still, there I was, in New York City, working for Marvel, living my dream of being a professional writer!

Stroud: You wrote quite a few scripts for Charlton back in the day in numerous genres to include humor, mystery and superhero adventures. Which do you think suited you best?

NoMan (1966) #1, featuring stories written by Steve Skeates.

Skeates: Wow! That's quite some leap, jumping from Marvel all the way on up to Charlton, and in the process bypassing all sorts of desperation, those heavy labor jobs I procured in order to put food on the table even as I was trying to get myself established as a reliable freelancer, plus there was even another comic book company in there as well, one I worked for on a regular basis in-between Marvel and Charlton! Far from a well-established firm, a brand-new entity is what this baby was, something that seemingly just suddenly popped up from out of nowhere (then, unfortunately, but a few years later, once I had really truly gotten into the swing of writing for these people, this upstart of a company bit the dust in what I can only describe as an equally spontaneous fashion!). Still, I don't wanna make too big a deal out of the work I did for Tower Comics (yep, 'tis indeed that particular concern helmed by Harry Shorten, Sam Schwartz, and Wallace Wood that I am indeed talking about here!), seeing as, back in that particular day, I was still learning the ropes, still groping my way around, and, more often than not while attempting what I usually figured was a clever-to-the-max bit of business I would resoundingly fall flat on my literary face! Oh sure, there are (as a matter of fact) pieces I produced for Tower that I'm actually proud of (like what in my estimation is the very best collaboration I ever performed with the great Gil Kane, an Undersea Agent tale entitled "To Save A Monster"), yet, all in all, I was there basically honing skills that I would put to far far better use once I made the scene at Charlton and got involved in all that variety you just now spoke of. That is to say, although I had already worked on four fairly interesting westerns at Marvel (the most controversial of which – if, that is, you can swallow abject silliness, a pervasive too-far-over-the-top flavoring, and a storyline that comes off more like a superhero adventure than any sort of actual western drama as somehow being "controversial" -- was a Kid Colt sagebrush saga that Roy Thomas helped me plot; as a matter of fact, Roy ultimately, once said comic had hit the stands, got called in on the carpet by his boss, none other than the aforementioned Stan Lee, concerning this particularly crazed collaboration of ours, whereas by then I had already left Marvel and moved over to working for Tower, making for Roy being the only one who got dressed down for all those silly plot twists and unwarranted far too bizarre character developments that had essentially sprung forth from my so-called mind rather than from anything of a similar ilk that Roy possessed.

Kid Colt Outlaw (1949) #219, written by Steve Skeates & Roy Thomas.

As for my other three Marvel westerns, they were all beautifully drawn by the great Dick Ayers and starred that ever-popular masked do-gooder known as The Two-Gun Kid -- one even featured Two-Gun bumping into that real-life legendary outlaw known as Billy the Kid), and although I had (at that aforementioned place I subsequently moved on to) also provided scripts for a number of short, punchy, ten-page mini-epics detailing the adventures of various superheroes of a decidedly secret agent sort (thirteen Lightning stories, six NoMan episodes, a couple of tales chronicling the antics of just about all the Thunder Agents – and quite the cumbersome, multi-powered, getting-in-each-other's-way crew that was, lemme tell yuh! -- plus six or seven Undersea Agent yarns), it wasn't until I made the scene at Charlton that I was given what can best be described as a vast variety of genres in which to immerse myself! Superheroes, however, had very little to do with my experience at what turned out to be my all-time favorite company to work for! In fact, there were only two stories I worked on during all my years at Charlton that could properly be referred to as superhero sagas! The first was something I created as well as doing both the plotting and the scripting, a ten-page tale introducing the heroic efforts of three college students who just happened to possess the power to telepathically communicate with one another (this was their only superpower, as a matter of fact) and who called themselves The Tyro Team, a crime-fighting tale sandwiched in-between a couple of other superhero try-outs (by other authors, of course) there within the very first issue of something called Charlton Premiere – the idea being that the series idea that received the most favorable fan mail would be awarded its own book, but, unfortunately, by the time that mail arrived the entire Charlton action hero line had been unceremoniously cancelled due to slumping sales and just about everyone who had worked on Premiere had left that company and was now working over at DC! But I don't wanna get ahead of myself here, so let's jump back to Charlton, as I point out that the other superhero piece I worked on there had been merely a dialoging job that (in fact) I even did under a pen name!

Hercules (1967) #1, featuring the first Thane of Bagarth back-up story by Steve Skeates.

What there were, though, there at Charlton, were westerns -- sagebrush scenarios that seemed more adult in their attempts to capture the pathos of life in the old west, far far more adult than anything that had been going on years earlier (in fact, it was still going on, though I of course was no longer an active participant) over at Marvel! Kid Montana, Captain Doom, Outlaws of the West, Gunfighters – characters and comics that had a dark and brooding edge going on in there! And, speaking of all the various genres, there was more, much more, happening here! For but one example, there was the chance I got to develop that caption-heavy Prince-Valiant-like seemingly endless historical pastiche known as The Thane of Bagarth (based, in fact, upon what little I could remember from my college days concerning the legend of Beowulf), which, as it turned out, became the initial series that was produced by those who in the not too distant future would become best known as the late sixties/early seventies creative personnel behind Aquaman, i.e.: Dick Giordano, Jim Aparo, and myself! Still, let us not forget the ghostly stuff (The Many Ghosts of Doctor Graves, Strange Suspense Stories), nor the humor (something called Go-Go as well as Abbott and Costello)! Plus, there was even a private eye in there (Sarge Steel, both as a back-up series in the Judo-Master book and in his own book which rather enigmatically sported the title Secret Agent!)! Like I said, quite a nifty variety!

Dick seemed to think that humor was my long suit, but that might merely be because there were so few people in the comic book industry who knew how to write humor (a situation which unfortunately still has an insistent grip upon a definite majority of those who work within the comic book biz); thus humor became the most valuable commodity I possessed, while nevertheless not necessarily being my forte! Meanwhile, fellow Charlton scribe (who soon would be joining me and a number of others in our giant leap on over to DC) Dennis J. O'Neil somehow came to the conclusion that the Thane of Bagarth was the best thing I was producing! As for me, back in the day, I personally felt that the westerns (which incidentally rarely carried any by-lines) were the best that I had to offer! Nowadays, however, it suddenly appears (to me, at least, having just now once again perused much of what I did way-back-when) that it's actually my ghostly output that has deftly grabbed the coveted brass ring within that ratings game known as the proverbial test of time! What strikes me as being an especially interesting aspect here is how much work (especially considering how little I was getting paid back in those days), how much thought and intensive creative energy I obviously poured into such tales as "The Best of All Possible Worlds," "The Ghost of Man," and "One Last Chance!" I was definitely giving these things my all, and that does indeed show! Of course it doesn't hurt that these three tales (as well as so many of my others) were drawn by Jim Aparo, Pat Boyette, and Steve Ditko, respectively!

Secret Agent (1966) #10, featuring stories written by Steve Skeates.

Stroud: Do the names Warren Savin and D.C. Glanzman mean anything to you? When Denny O'Neil told me about his Sergius O'Shaugnessy alias he said it was to make sure he was free of the stain of being a comics writer. Was that your modus operandi as well?

Skeates: Sounds more like a gag line on the part of O'Neil than anything even partially resembling a full disclosure of actual factual details, especially considering that Denny's real name was right out there in plain sight on a number of comics that were being published at the same time as those that bore his bizarre Sergius O'Shaugnessy moniker!

The former were Marvel comics; the latter were Charlton products. And, instead of trying to hide from the ignominy of writing for anything as overwhelmingly salacious, as utterly in the gutter, as comic books, what Denny was really up to was attempting to work for two companies at the same time back at a time when Stan Lee demanded total exclusivity from anyone and everyone who worked at Marvel!

Not that it was a bad gag, mind you – you know, something that has no connection whatsoever with reality! After all, when Denny and I first got involved in comics there were still a number of people involved in that industry who flat-out didn't want to publicly admit that comic books was what they did for a living! Mainly writers and editors, many of who (for whatever reason) were currently working at DC – people who had been producing stuff for one or another of the comic book companies back when Dr. Frederic Wertham, The Reader's Digest, and the United States Congress placed that big fat stain upon the entire industry! Writers and editors who in the fifties couldn't help but react to what was being said about their means of feeding their families (that comics were some sort of pornography of violence, that they warped children's mind, that they were the direct cause of a number of childhood suicides) with oodles of shame, and still, in effect, as late as the seventies, carried the stain of that shame around with them, even though pretty much the whole rest of the world had long since come to see the comic book witch hunts of the fifties as having been but another instance of a paranoid Puritanical overreaction typical of that era (seasoned, in this case, with a unhealthy dash of parental buck-passing); thus the lingering effects of that insanity, I would venture to guess, is mainly what O'Neil was making fun of!

Blue Beetle (1967) #4, featuring the Kill Vic Sage back-up story co-written by Steve Skeates.

But enough of that! Let's quickly now move along to my heartfelt desire to totally disown that silly D.C. Glanzman appellation! I am of course well acquainted with the fact that there has been for years a rumor extant that I'm the one who wrote under that name, but, as I've said before and will undoubtedly be forced to say again, that simply is not true! I furthermore have no idea what the actual reality of this situation was, yet there's another rumor that I feel makes a lot more sense than that one about me! The way this one goes is, first of all there really was (and maybe still is) someone named D.C. Glanzman, someone who worked in the main office of Charlton Comics up there in Derby, Connecticut! From what I was told, he was a relative of that popular war story and western artist (and all-around nifty individual) Sam Glanzman! Also, good ol' D.C. may have even helped polish some of Steve Ditko's dialogue for both the Blue Beetle and The Question! In any event, D.C. allowed his name to be put upon those stories, whereas something like 98% of the scripting work on those tales was actually performed by Ditko himself!

I will, however, own up to the fact that Warren Savin was indeed a pen name of mine! What I find most fascinating here is that quite a few people seem to think I wrote a fairly large number of stories in which I employed that pseudonym, whereas, in all actuality, there was a sum-total of but one story that I slapped that particular moniker upon! Yep, only one! And, within that one I was essentially doing what I just now speculated as to being the major contribution to the scripting process provided by D.C. Glanzman, although (being a bit of an egomaniac) I would like to stress that there (within that story generally referred to as "Kill Vic Sage") I performed a bit more than a mere 2% of the labor involved in making this particular eight-page story such a memorable (if I do say so myself) reading experience! The plot was all Ditko's, as was the first draft of the dialogue! What I mainly tried to do was soften the shrillness of that dialogue, make it a little less like everyone was overreacting to everything! Make those demonstrating against Vic Sage seem a bit more reasonable, a bit less like a mere parody of an actual demonstration! Even tried to make The Question a bit less of a stiff, and, in the latter, I may have gone a bit too far, seeing as I received a six-page letter from Ditko detailing why The Question would never say what I had him saying. You can even see (in panel five on page five) where some of my dialogue that Ditko found particularly offensive was just before publication hastily removed! After that, I'm still surprised that Ditko didn't vehemently object to my being chosen to do the dialogue for The Hawk and The Dove!

The Hawk and The Dove (1968) #1, written by Steve Skeates.

But, to actually answer your question, it was mainly due to some misplaced modesty that I wrote The Question under my Savin pen name! Since I was slated to take over the scripting chores on both of the series in the Blue Beetle book (a deal that fell through due to the aforementioned cancellation of the entire Charlton action-hero line and the fact that that led to a large portion of the talent at Charlton leaving that company and moving over to DC), I had strangely decided that it would be somehow unseemly to have my name on both stories in that book, that it would come off as too egomaniacal or something like that! Therefore, I had decided to do the main series (The Blue Beetle) under my real name, and to employ a pseudonym on the back-up feature! As things turned out, as I just now indicated, I never did get to write the Blue Beetle, but at least I got to work on "Kill Vic Sage," a story so compelling that it is still (after four decades) continually discussed and argued about on-line and within various fan publications!

Stroud: I've heard a couple of slightly differing stories about the move of the old Charlton alumni to DC. How do you recall the time?

Skeates: My most vivid memory of that particular period is all about a certain quantity of inwardly-focused recriminations, each laced with a hefty layer of both fear and neurotic self-loathing, balls of blame and self-doubt that started bouncing around in my brain as soon as I had somehow (for some unfathomable reason) forced myself to say over the phone to Dick Giordano: "Sounds like a good idea to me!" Obviously what I'm speaking of here is Dick back there in 1968 having just informed me of his reaction to the higher-ups at Charlton abruptly canceling that company's entire action-hero line, of how he now planned to move from Charlton over to DC, while, within the midst of that recitation of his determination, even making mention of his hopes of being accompanied there (if we were agreeable) by Aparo, Boyette, Ditko, O'Neil, and myself, whereas I (clearly in a moment of idiocy) had just voiced my approval, my acceptance of my role in what Dick was planning, making for what had almost instantly begun to bounce about up there within that squishy gray slop at the top of my head to ultimately manifest itself as a batch of inquiries, plaintively shouted, frantically growing louder and louder -- questions like "What have I done?" and "What have I gotten myself into?" repeated over and over again! After all, in that attempt of mine in the mid-sixties to pick up as much freelance comic book work as I could possibly get my hands on, I had visited DC on several occasions, and I had found it to be a very unfriendly place – snotty, snooty, stiffs in suits and ties with no indication within those offices that this was where comic books were put together (editorially-speaking) – no pictures of superheroes on the walls, no stacks of what they produced anywhere to be seen! It all came off like I was visiting a bunch of CPAs! Or a bunch of pallbearers! And, since I was more casually dressed than these people, looking more like a comic book person than did any of the stiffs who actually worked there, what I mainly received from those folks was a collection of uptight self-righteous superior-being sneers!

Creepy (1964) #47, featuring stories written by Steve Skeates.

DC Graphic Novel (1983) #2 - Warlords, written by Steve Skeates.

Howard the Duck (1979) #9, featuring a story written by Steve Skeates.

And then, there was what they actually produced! Comic books that were nearly as stiff as they were, stories at least twenty years out of date, employing slang even older than that! Like still using the word "hep" – how utterly ancient can anyone get? Sure, I knew (as we all did) that we were set to get plunked down within this surreal variation upon the mummy's tomb (or something like that) in order to give that half-dead company an infusion of new blood, but would that work? Or, since we'd be outnumbered, would it all get turned around, with the six of us ultimately being forced to produce typical DC stuff? – stiff, boring, lackluster, with those usual big blocky unnecessary captions, ones that would heavy-handedly inform the reader of what he had already figured out for himself simply by looking at the art! Arrgh! Luckily, my fears were far from realized!

The Flash (1959) #202, featuring a Kid Flash back-up story written by Steve Skeates.

Having made judgments based on fairly superficial data (rarely a particularly wise or even slightly accurate means of predicting much of anything at all), I had severely underestimated the desire on the part of just about everyone who worked in those sterile and stogy DC offices to have that institution become once again a viable company, an actual money-making concern, worthy competition for that seemingly both in-the-know and in-the-now cross-town rival of theirs known as Marvel! After all, it had been DC that had started the sixties superhero revival, testing the waters via tentatively reintroducing characters like Green Lantern and the Flash (i.e.: doing so within their Showcase title) and thus discovering that there was indeed a new crop of kids out there who wanted to read about superheroes! However, once Stan Lee tumbled to what it was that DC had just discovered, he lost no time in veritably flooding the market with his own brand of superdudes -- characters with a sixties edge to their psyches, flaws that endangered their heroic stature, actual infirmities that made their choice of occupation seem even further over-the-top within the realm of the utterly outlandish, past mistakes and disconcerting transgressions discoloring their view of the future, a truly unruly crew of angst-ridden guilt-ridden infirm tortured neurotic misfits -- and, in doing so, had whipped the sales right out from under DC!

For nearly a decade DC had been essentially merely going through the motions, publishing as few comics as it could get away with while still keeping the company somehow alive, just barely alive, comics that had hardly changed at all story-wise character-wise in well over ten years, just the sort of tired lackluster fare you'd figure would flow forth from those who were basically sleep-walking through their jobs, and do let us not forget that many of these people had had their souls virtually shattered and were still uncomfortably numb from the effects of the aforementioned witch hunts of the fifties. Then suddenly these people discovered a new burgeoning ripening interest in the antics of superheroes, and they'd be damned if they were gonna let those self-satisfied self-congratulatory cretins over at Marvel steal what they had stumbled onto!! Then again, though, it had just become quite obvious that the sorts of comics these people were used to producing were simply not gonna cut it anymore, especially if they wanted to wrest back what Marvel had grabbed away from them! In other words, what was needed here were characters more like the ones that Stan was already busy as hell constructing all sorts of adventures around, characters that actually had a modicum of personality in there, plus stories that not only possessed some oomph to them but also actually spoke to the times, to current reality! In short, then, what these people needed (and even wanted) was someone (or, more accurately, a bunch of someones) who could wake them up and drag their half-dead carcasses into the second half of the twentieth century! And, that's why the six of us were there – to take the point, to lead these injured souls out of that morgue of their own making and into a place where they could honestly be productive!

Teen Titans (1966) #28, written by Steve Skeates.

Stroud: They seemed to use you in a number of different arenas at DC. I found credits for stories in such diverse offerings as Supergirl, the Teen Titans, Plastic Man, Phantom Stranger, the Spectre, Aquaman (of course) and Plop! Where do you feel your talents worked most effectively?

Skeates: The way I see it, talent (and I'm not all that comfortable with that term, seems a bit pretentious, a tad "grandiose," elevating something that's mainly comprised of the hard work of learning one's craft up and up and up to the silly level of supposedly being some sort of innate ability that's God-given, but for the sake of getting down down down to what I want to say here, let us, at least for the moment, let slide my objections to the term itself) is (as that previous parenthetical comment has already made pretty much perfectly clear) not something that's solid and pre-set and in the business of looking for the proper and fitting venue in which to unfold itself! So-called talent is instead a changeable thing, particularly affected by the forever madly fluctuating worldview of the individual who is said to possess that talent! And, all of that makes for there being more than one answer to your inquiry here – a multitude of answers actually and all of them revolving around my being in the right place at the right time; yet I'm not speaking of the "right place" externally; I'm talking about the place I was in within myself!

Take Aquaman for example – I landed that assignment at a time when I was young and innocent enough to believe in the actual possible existence of a super altruistic good guy, whereas later certain things happened to me within the comic book industry itself – books I enjoyed working on were cancelled for some reason other than poor sales (which is the only reason books should be cancelled), editors repeatedly went back on their word, costing me not merely a bunch of sleep but quite a bit of moolah as well, and I even lost a number of writing assignments to writers who couldn't hold a candle to yours truly in the creative sweepstakes, getting blind-sided and shafted thanks to their employment of sleazy office politics to procure for themselves work that should have been mine, etc., etc. – things that caused this raconteur to grow bitter and cynical, and suddenly I was no longer any good at producing believable superhero epics; yet this was when I started pulling in all sorts of awards for writing humor and horror, both of which were definitely at that point a far better fit than those guys who ran around in leotards and flew with the aid of a cape!

Aquaman (1962) #40, written by Steve Skeates.

Furthermore, to bring these proceedings rather up to date, I do quite honestly believe (what with the passage of so many years, as well as this particular individual in various recent interviews looking back at his career and finally realizing how lucky in so many instances I really was) that now at last I've calmed down a bit, learned even to forgive, and am no longer encumbered by various grudges the holding of which undoubtedly hurt me more than I inflicted any damage upon anyone else, and thus I may (in fact) (for whatever it's worth) even be ready to write superheroes once again!

Stroud: Many terrific artists have interpreted your scripts, to include Bernie Wrightson, Bill Draut, Jim Aparo, Chick Stone, Steve Ditko, Sergio Aragones, Dick Dillin and Frank Robbins. Was there anyone in particular that you felt really got the feel of your stories?

Skeates: My initial impulse here is to add names to the list – Gil Kane (whose work on "To Save a Monster" I've already mentioned), Ogden Whitney (having been a big fan of Herbie The Fat Fury, it was indeed a thrill to have this dude illustrate a number of my NoMan stories over at Tower), Pat Boyette (even though Ditko and Aparo also worked on the book, Pat was hands down my favorite when it came to someone who'd embellish my spooky offerings for The Many Ghosts of Doctor Graves), George Evans (that first mid-seventies Blackhawk story the two of us put together is definitely up there, amid the top five favorites of mine vis-à-vis any specific comic book I've ever gotten involved in), Ramona Fradon, Mike Sekowsky, Tony DeZuniga, Gene Colan, Marie Severin, Jaime Brocal, Alex Toth, John Buscema, Alfredo Alcala, Ric Estrada, and what can I say about a guy whose work I had revered from as far back as the fifties, back when (as a twelve-year-old) I had a subscription to the original comic book version of Mad? And, yes, I am indeed talking about that creative powerhouse known as Wally Wood! The only problem with all of this is that there are so many – rarely respected artists who did fine by me, big-name illustrators who were truly a pain to work with -- too many even when you don't even consider every category imaginable, making for the distinct possibility that I've already accidentally left out someone who was extremely important and perhaps even somehow instrumental in shaping my career!

Plop (1973) #1, featuring "The Gourmet" written by Steve Skeates.

Be that as it may, however, let us nonetheless (in order to keep these proceedings from, say, sinking to the bottom of some mossy swamp of utter minutia, or whatever) move right along now to a couple of the names you mention – specifically, Wrightson and Aragones, highly individualistic artists who (obviously!) helped me immeasurably in the landing of at least two of those Shazam Awards I picked up in the seventies and were as well undoubtedly more than a little responsible for this particular tale-spinner winning those other two chunks of congratulatory Lucite I glommed onto back in those crazy days! The way I see it, no way would "The Poster Plague" and "The Gourmet" have been recognized as the best humor stories of 1972 and 1973 respectively had Sergio and Bernie not perfectly (interestingly enough, via such utterly differing styles) pounced upon the feel of what I was up to vis-à-vis these strange little dramas, call them "humorous horror stories" or "horrible humor stories" – the nomenclature, though admittedly one of the choices here does seem to possesses more than a smattering of the pejorative, is nevertheless entirely up to each individual witness to one or the other or both the destruction of a certain college campus and the freakish fate of a certain fat man! In retrospect, however, what I actually find most puzzling here (especially in the case of "The Gourmet") is how little follow-up there was! I mean, despite the well-publicized actuality that on our very first job together Bernie and I had reeled in one big fat prestigious award (for, in fact, a story that has gone on to be reprinted more often than any other comic book tale I can in all honesty think of), we were weirdly never asked to team up again, obviously making that first collaboration of ours the only one we ever got to do! Of course one might conjecture that we simply didn't possess enough available time to get it together for a repeat performance, Bernie having suddenly gotten so enormously busy with all those early Wein-Wrightson Swamp Thing adventures he was illustrating, whilst I was simultaneously quite occupied producing scripts for House of Mystery, House of Secrets, Weird Mystery Tales, Forbidden Tales of Dark Mansion, Secrets of Sinister House, and Plop, leaving the decision as to who would be drawing whatever story of mine you're wondering about totally up to the editor, Joe Orlando. As to the strangeness of Joe apparently simply never thinking to give one of those stories to Bernie (something I'm now rather baffled about), do allow me to expand upon that lack-of-time theme I just mentioned by pointing out that surely said phenomenon included when it came to this particular scripter an absolute absence of minutes set aside for the expressed purpose of wondering why something-or-other wasn't happening, especially when you consider (for example) that the horror books were not the only ones I was working on for Joe; there was also Adventure Comics featuring Supergirl and Captain Fear! There was Jimmy Olsen! And there were those various back-up stories I was producing for the Phantom Stranger book. And, let us not forget the other editors at DC I was working for, not to mention the other companies I was selling scripts to! I was spread (lemme tell yuh!) way too thin and leading a truly frantic existence, with little time to contemplate the overriding weirdness of (now that I stop to think about it) many a seventies' editorial decision!

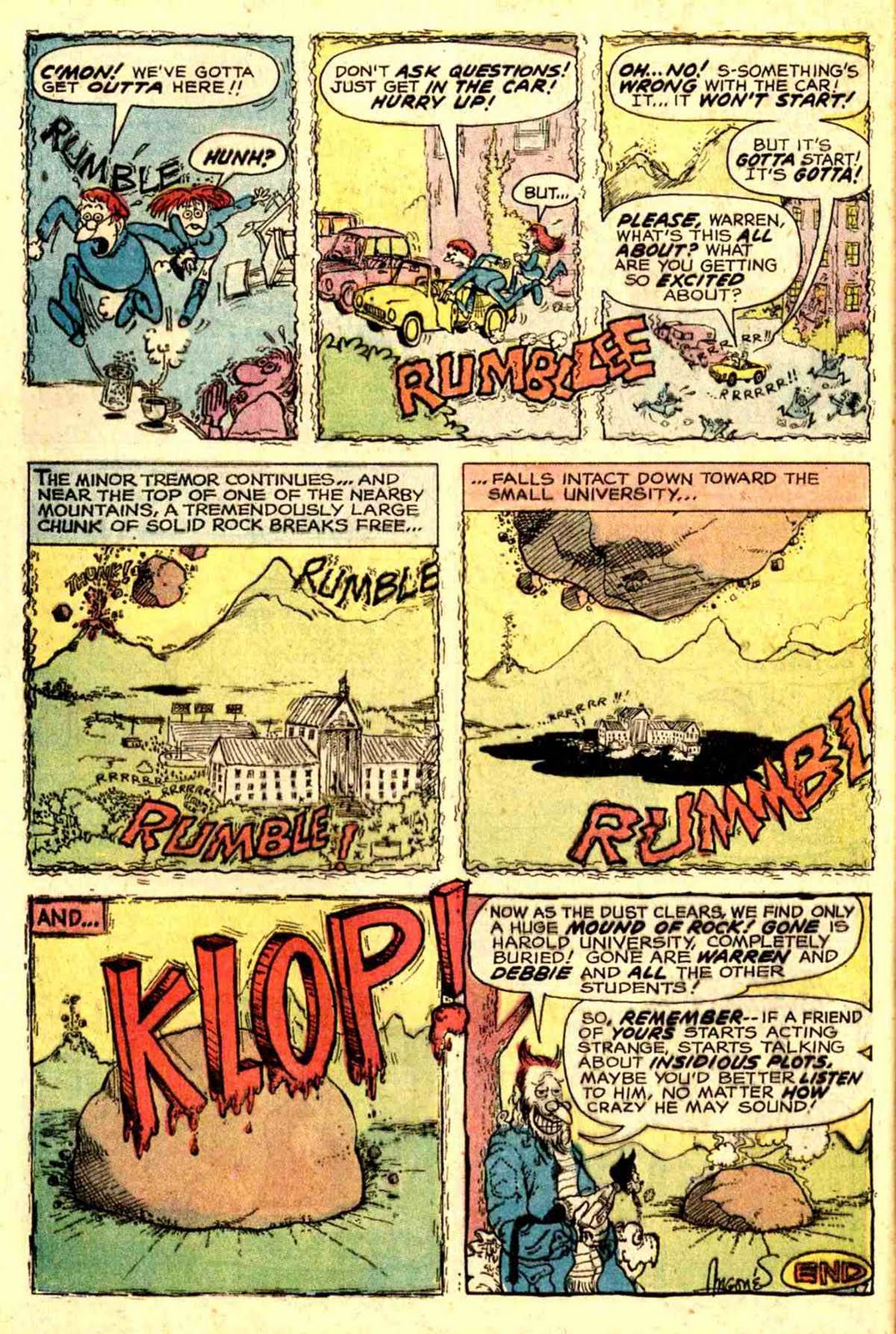

House of Mystery (1951) #202, featuring "The Poster Plague" written by Steve Skeates.

Things stacked up in a much more reasonable and logical fashion as far as Sergio was concerned, with the two of us collaborating on quite a number of crazed yarns that quickly followed in the wake of "The Poster Plague," the best of which were undoubtedly "A Likely Story" in Plop #8 and "The Secret Origin of Grooble Man" in Plop #10! Those two potboilers (plus a number of the other collaborations I just now mentioned) quite likely elicited the requisite number of giggles, guffaws, and chuckles, I suppose, yet none of them (I'm sad and even halfway embarrassed to say) came anywhere near the general vicinity of possessing the sort of underlying structural integrity comprised of serious subject matter compellingly presented as that which (in fact) informed our initial collaboration -- specifically, a believable intellectual atmosphere in which our main character's theorizing has gone seriously awry via taking a turn toward a certain sort of paranoia, the seemingly insane delusional variety which nonetheless ultimately proves itself to not be all that crazy after all but instead the harbinger of some pretty damn deadly fruit, with worthy characterization and even a hint of the autobiographic thrown in for good measure!

Oh well, it's hardly a well-kept secret that when one is writing for a living, no way can every single thing said writer produces be a gem! In fact, the general consensus amongst all the other writers I've talked to about this tends toward being that there's a 25-50-25 split going on here, i.e.: twenty-five percent of what you write is great, stuff you can truly be proud of; fifty percent is so-so, with another twenty-five taken up by those pieces that truly suck! The trick is to make the so-so stuff and somehow even the sucky stuff just passable enough so that you don't get fired! And, in point of fact, what I just now described is definitely where I was at in the seventies! However, I'm not all that convinced that this was how things worked for yours truly a bit earlier than that, back (that is to say) in my Charlton and early DC daze!

Hey now, say now, don't get me wrong here -- I'm not trying to imply that I was once different from all those other writers I was just now blathering about, that I was once better than any of them, better than all of them put together, or anything like that! The truth of the matter is, I think this happens to a lot of us when we're younger, especially when we land the proper character and get teamed with what each individual amongst us would deem his own personal best of all possible artists! And what I'm talking about here is climbing aboard a roll, hopping astride a sweet something powered primarily by youthful enthusiasm wherein the great stories just keep coming, the so-so tales become a rarity, and the icky sucky stuff takes a powder, slinks off to some Republican graveyard somewhere and politely bites the dust! As for that 25-50-25 deal, I have no idea how that caught on or why so many people have wound up believing that bilge, but I will say it's my honest opinion that those figures were originally devised by an older author as a way of saying "most of my stuff may be pretty terrible, but that's how it is with everybody else too!" Yeah, right.

Gunfighters (1966) #52, featuring stories written by Steve Skeates.

Furthermore, pursuant to serving more than one god, let it at last be known that everything within those previous two paragraphs (the very ones you have just now perused) has come here this evening to proudly stand acutely self-evident as but a portion (albeit an integral portion) of an indication (complete with bells and whistles) that this insufferably verbose storyteller is now finally (can you believe it?) about to provide an actual answer to your long-standing "get-the-feel-of" inquiry, and that answer is Jim Aparo! Or, to get right down to it, while working with Jim on a number of mystery stories, plus that Thane of Bagarth series in the back of the Hercules book, and even a western, something called "The Coward" which made its appearance in Gunfighters #52 (all of that for the folks at Charlton), I came to realize that Jim and I were (to employ rather appropriate sixties vernacular) pretty much on the same wave-length, that we seemed (that is to say) to somehow view reality is the same "quirky" manner! Thus, as but an example of what was happening here, as time passed the picture descriptions I'd provide within those specific scripts of mine that would be sent to Jim became shorter and shorter, less elaborate, less specific, because I began to trust (implicitly!) that with but a few words (sometimes, believe it or not, it'd only be one word) that Jim would immediately firmly grasp what it was I wanted him to draw! Best of all, though he would often give me more than I expected and in doing so very pleasantly knock me for a loop, more importantly he would never ever give me anything less than what the story needed! As all those superlatives undoubtedly make fairly obvious, now all we needed to get aboard one of those aforementioned rolls was to be given the proper character! Then, when the two of us (along with Dick, Denny, Ditko, and Pat) moved on over to DC, Jim and I were handed Aquaman!

Stroud: I found you've written for virtually all the publishers such as Tower, Seaboard, Archie, Marvel and a long run at Warren. How did they compare? Did you feel more artistic freedom at any particular publisher?

Weird Mystery Tales (1972) #4, featuring stories written by Steve Skeates.

Skeates: Ah, yes, freedom for those who toil so strenuously within the sun-drenched fields of Art, that forever-sought-after forever-wished-for forever-dreamed-of bombastic release from what can only be described as the unspeakably emasculating shackles of editorial restraint! Or, am I perhaps overstating the case just a smidge here? I do quite honestly suspect, after all, that "artistic freedom" means something slightly different to each of those who have somehow come to consider themselves (whether rightly or wrongly) to be within that elite conclave known around these parts as The Art Gang! And, of course (especially within these particularly troubled times wherein economic considerations too easily infect everything anyone attempts to discuss) I must say that seeking that aforementioned freedom (no matter how it is described) can often be downright monetarily counterproductive, garnering you a dollop of respect from your peers whilst simultaneously putting you upon the path to the poorhouse! Furthermore, in my particular case, my desire for "artistic freedom" may go a long way in explaining various aspects of my so-called career which otherwise (upon, for example, the usual journeyman journalist's cursory examination) might seem quite utterly enigmatic! Consider, then, though it paid a mere pittance when compared to the loot one could glom onto at DC and Marvel, Charlton nonetheless remains my favorite among all the companies I ever worked for! Now, add to that the fact that I definitely never (as much as I could have anyway) pursued working (on a far more regular basis than I did) under the influence of that highly respected editor, Julie Schwartz! And, while you're at it, you might as well throw in there a consideration as to why I never warmed up to what is generally referred to as The Marvel Method!

Taking that trio of bizarre happenstances in order, then, let us attack my attitude toward Charlton by first of all examining a certain statement John Schwirian made during his interview with this particular author! In reviewing the Abbott and Costello book I did for Charlton, John not only said my stuff therein was rather funny; he also pointed out that he liked it better than the Plop material I did later on! I of course continue to stand by my response that I'm still way too close to those two books to make any sort of informed judgment as to which contained the funniest material; however, if Abbott and Costello is indeed funnier than Plop, I'd say the reason for that lies in the hands of our old pal Artistic Freedom! After all, up at DC, in order to do up a Plop story, I had to come up with a plot outline, type up said outline, talk that over with the editor, get told the page count by the editor, and then finally go write the story. And, really now, nothing kills comedy faster than belaboring it. As for those earlier efforts of mine, that stuff starring Bud and Lou, I'd come up with an idea, plunk myself down at the typewriter, and just start writing, to some extent allow the story to write itself, allow various jokes that weren't part of the original idea to worm their way in there, and just keep going until I was done, making the story as long or as short as I wanted it to be. You ask me, that's the way that sort of stuff should be done.

Eerie (1966) #33, featuring stories written by Steve Skeates.

Moreover, what with the truth hopefully herewithin getting laid out like we're in the business of performing an autopsy upon it or something, do allow me to indicate that (when all is said and done) I'm really not merely speaking of humor pieces here; I'm embracing the entire magilla, which is to say what I just now described within that previous paragraph is in fact my preferred manner in which to write any comic book story – devising the mere rudiments of an idea that somehow vaguely resembles a plot and immediately immersing myself within the writing of that tale, letting that aforementioned so-called plot develop even as I'm typing up the particulars of the piece! That, as matter of fact, stands as pretty much the bulk of my own private definition of "Artistic Freedom" – being able to avoid having to write (and then even get approved) a preliminary plot outline and thereby boxing myself in, severely limiting my own freedom! Furthermore, that's why I loved working for Charlton – they allowed me to work in my preferred manner; only once during the years I worked there was I asked to produce a preliminary plot outline!

Sometimes, back in those days, to get right down to the particulars here, I wouldn't even know how a story of mine was going to turn out until I reached page five or six of a nine-pager and would suddenly have a revelation as to where I was really headed! In that way I would often be as surprised as hopefully ultimately the reader would be, and that was definitely a major part of the fun of the process! Oh, sure, there were problems that would arise vis-à-vis this particular approach – writing myself into a corner, coming up with a yarn that started well but then just sort of petered out! But that was offset by those tales that I already did have an idea for the ending to, yet halfway through writing the piece I'd come up with a much much better ending and be very happy that I could actually do it the new way, that I wasn't hemmed in by a previously approved plot outline, as surely would have been the case at DC or Marvel! Certainly, the editors at those two larger companies did tend to talk a good game when it came to their own so-called flexibility! More often than not, though, in reality they were stiff as a board, and it was close to impossible to talk them into changing the ending of a plot that had already been approved!

Peter Porker, The Spectacular Spider-Ham (1985) #1, written by Steve Skeates.

There was, though, of course, far more to the problems I had at DC and Marvel than something that so rarely arose anyway as trying to get an ending to a previously approved story changed. At Marvel there was for example that thing called the Marvel Method, that whole plot-then-pencils-then-script-then-inks idea, an approach to comics that (in my honest opinion) made for an even tighter straight jacket that I had to ensconce myself within! I mean, not only was everything in the story worked out in advance preliminary-plot-outline-wise (making the actual writing of that story, in my opinion, rather a bore), but at Marvel the actual flow of the piece was taken out of my hands as well and given over to the penciler. Certainly, I can see why certain writers would actually prefer to have the artist work out the action and the flow, and maybe this makes me a bit of a control-freak or something! But, really now – I wanted to be the one who decided when to move in for the close-ups; I wanted to figure out where to place the jump cuts and the scene switches and all of that!

I never really thought of it this way before, but actually there was a definite similarity between my problems with the so-called Marvel Method and my reluctance to work with Julie Schwartz. Within the former case, decisions as to the pacing and the flow of a story would be ripped away from my control, while, with Julie, it would be the actual plot to whatever story I'd wind up working on that would no longer be primarily my own! Instead (generally) a writer would go into Julie's office with a couple of ideas, maybe three or four, nothing more than that, whereupon the two of them (the writer and Julie) would toss those ideas back and forth and back and forth and all around as they worked out a plot – a plot that would usually turn out to be mainly Julie's rather than the writer's! Hey, I love the way those World's Finest stories and that one Spectre tale of "mine" that I did with Julie turned out, but still (being a selfish bastard!) I wanted to write my own stuff, not his!

I do quickly wanna toss in here that my situation at DC was not anywhere near as bleak and dismal as the last three or four paragraphs may have seemed to make it appear. After all, at DC I was mainly working for Dick Giordano, the very editor who at Charlton had basically never required me to write a plot outline. Now that we had both moved on to one of the big companies, there was a bit of give and take (on both our parts) going on – I was putting up with having to write preliminary outlines, while Dick was putting up with those outlines being quite poorly written and rather sketchy, knowing that I was saving my good stuff for the stories themselves! Additionally, I was ultimately able somehow to convince Julie that a back-up series didn't need a big two-hour-long plotting session, that it would be better if I simply did those simple little seven-page Kid Flash stories I produced in the early seventies on "spec" – in other words, turn in a completed script without there having been any preliminaries whatsoever! Of course this meant that upon occasion Julie would flat-out reject one of those seven-page scripts I'd come in with, but even taking that into account, this was still my preferred way to work!

World's Finest Comics (1941) #203, written by Steve Skeates.

Stroud: Stan Lee has said that doing a continuing storyline allowed him to avoid having to come up with new material all the time. Did the "Quest for Mera" series in Aquaman serve in that capacity to a certain extent?

Skeates: Although your inclusion within this specific question of the phrase "to a certain extent" does go a long way in making me want to come down (albeit rather begrudgingly) upon the affirmative here, my answer (upon reflection) nonetheless still gravitates unerringly toward being one of denial, especially when one considers both intention and desire! In other words, there were all sorts of forces in play here that reached well beyond the itch to avoid having to devise new and different plots all the time. First and foremost is the fact that we were new to this character and furthermore wanted to take him in a new direction! Certainly no need, though, to barge off into anything so outrageous that it'd be like a baggy zoot suit or something of a similar uncomfortable ilk, some utterly bad fit for such a regal personage, particularly considering the vast quantities of unrealized potential that were sitting right there right in front of our faces, potential within both the sea king himself and that bizarre world in which he lived. The thing to do, then, would be to explore that world, to visit the various communities that abounded there at the bottom of the sea, and Dick figured the best way to accomplish that would be to send Aquaman on a quest.

So, no, I didn't (and don't) see the overriding plot here (Mera's kidnapping and Aquaman's search) as any sort of means of avoiding the construction of new plots; I saw it instead as but a momentary backdrop upon which to pin all the many new and different plots we were (in fact) downright eager to devise! The Sorcerers of the Sea, followed by that strange symbiotic society of the Depths, on into the savagery of the Maarzons, and Aquaman's adventures within each of these communities treated as though these were individual stories, tales with their own distinctive beginnings, middles, and ends, even as those aforementioned overriding concerns, elements that admittedly suggested that these weren't stories after all, that they were instead mere pieces of some larger whole – the sea king's seemingly endless search, his frustration, his mounting anger – allowed us to at last provide this formerly cardboard character with an actual personality.

Aquaman (1962) #42, written by Steve Skeates.

As to there even being back then a desire upon my part to avoid having to concoct new and different plots – no way, man! No way to the max!!

I don't mean to come off here all defensive (or self-aggrandizing, for that matter), yet I do want to bring to the fore my own frustration, even anger, over Dick's decision a number of months later to so soon upon the heels of our nine-issue arc present yet another multi-issue tale! You see, once our nine-part story had done its job (or what I personally mainly perceived as having been its job) of endowing Aquaman with a viable personality – strength and determination with just a touch of volatility, a touch silent, withdrawn, even a bit of a loner, yet all in all a downright likeable guy -- I wanted to immediately involve this stalwart character in a rather lengthy series of one-shots, single issue stories, self-contained 23-page yarns that would be satisfying unto themselves rather than dependent in any way upon any of the other entities within this or any other series! Unfortunately, Dick had other plans!

However, in order to immediately quash even the merest possibility of this particular bon vivant being categorized by those in the know (including especially a certain Mr. Giordano) as one truly ungrateful unreasonable (not to mention utterly miserable) misanthropic malcontent, do please allow me here and now to point out that what I'm talking about here was far far from being entirely (or even majorly) Dick's fault. That is to say that Dick (in point of fact) had absolutely nothing to do with getting the ball rolling here; instead this thing that at least I (honestly and subsequently) would term "a truly pathetic mess" was initiated by that ultimate evil known as the specter of illness! To elaborate, beyond being a consummate professional who would (as I indicated earlier) put his all into everything he did, Jim Aparo was the sort of artist who was into producing a page a day, and by that I mean doing up the entire magilla – pencils, inks, and letters! It was here that illness struck, making it impossible for Jim to ink any of what was to be the penultimate issue of our seemingly endless Quest arc, the episode entitled "The Explanation," whereupon I was asked to expand what was going to be the final issue of that arc from 23 pages to 30, then split it in half, so that it could be spread out over two issues (with reprints of older Aquaman stories employed as back-ups) thus considerably lightening the load that Jim would have to carry!

House of Secrets (1956) #105, featuring stories written by Steve Skeates.

Jim ultimately rallied enough to get back into doing a full book, truly putting his all (and then some!) into Aquaman #49, the first of what I was (as I just now indicated) hoping would be a long line of one-shots (as well as, in this particular case, being a rather brash attempt to demonstrate that the Skeates/Aparo/Giordano team could whenever we damn well felt like it easily produce the sort of socially conscious melodrama that O'Neil and Adams were so totally into over at the Green Lantern/Green Arrow comic), and I do indeed love the way this baby turned out – the totally wordless two-page introduction, that fist fight within a burning factory, the sympathetic qualities of "the villain" nicely played up in the artwork! Yet, all of that took a lot out of Jim and put him on a path toward a possible relapse; thus he requested that he be able to go back to doing but fifteen pages an issue, at least for a while.

The thing is, Dick at this point had no desire to once again use reprints for the back-ups -- the response to the ones he had employed in issues 47 and 48 had hardly been of a positive nature; thus he wanted to do something new and original this go-round, something that would in fact help draw even more readers into becoming regular members of our audience! Furthermore, Dick also wasn't particularly taken with the idea of our doing at the front of the book a series of fifteen-page one-shots (although personally I still contend that that would have been a far better idea than that lame three-issue lost-in-Mera's-ring storyline that we ultimately settled upon). Or, to expand upon what I just now mentioned parenthetically – what evolved here was a three-parter within which the sea king was basically trapped within a bizarre alternate reality and was trying for all he was worth to find his way back to Atlantis so that he might be reunited with his Queen, a storyline essentially devised by our aforementioned editor and one which (at least in my opinion) bore way too many similarities to that nine-part extravaganza we had finally put the kibosh upon but a few issues earlier; this new one, then, coming off like some weak-kneed watered-down sad and lackluster imitation of that quite brightly-lit chunk of fiction we had not long ago just spent a year and a half producing! And, as for the back-up here, there was a three-part Deadman adventure written and drawn by Neal Adams that somehow interacted with this utterly unfortunate Aquaman retread!

The Generic Comic Book (1984) #1, written by Steve Skeates.

Judging from everything they said and did as well as the work they produced, Jim, Neal, and Dick were totally into this project! As I believe I've sufficiently indicated, I was not! Yet, I did try to suck it up and be professional about this situation I suddenly found myself trapped within, tried hard to write it well despite not being into it, even added certain elements I do quite like, such as the bubble-guns and a weird religion wherein conversation outside the confines of a church is seen as a sin!

I mention all of this because beneath my frustration over having to participate in this travesty was my desire to get back into doing up that batch of one-shots I had merely scratched the surface of back when we produced our socially conscious 49th issue, a desire that I must say stands as more or less the exact opposite of the attitude you quoted Stan Lee as speaking in favor of! I wanted more than anything else to come up with some new material, to devise a whole bunch of stories, sagas, sea chanteys (if you will) that would stand on their own! And, finally, after merely a half a year (with Jim now apparently fully recovered), I at last got my wish, and we were able to produce what I still contend are the three best issues of Aquaman ever (plus a fourth one that wasn't half bad either) – "Is California Sinking?," "Crime Wave" (I do indeed consider it an utterly out-of-this-world honor that a number of critics have cited this one as being an Aquaman tale as though written by Philip K. Dick – like I might ever be in a league with that dude!), "Return of the Alien" and "Computer Trap" (definitely this issue was the clunker of the four, yet the two stories here did allow me to establish some of the sea king's more liberal political attitudes whilst simultaneously enabling me while still holding on for dear life to the last vestiges of being in my twenties to do up a tale based upon that silly hippie axiom, "Don't trust anyone over thirty!"), and finally supposedly the best of the lot, "The Creature that Devoured Detroit!" Hey, talk about being on a roll – a Kaiser with poppy seeds I believe it was!!

There's more, of course! There's always more that can be said! Yet, I do like that as an ending! Just the proper amount of not taking all of this all that seriously! So…

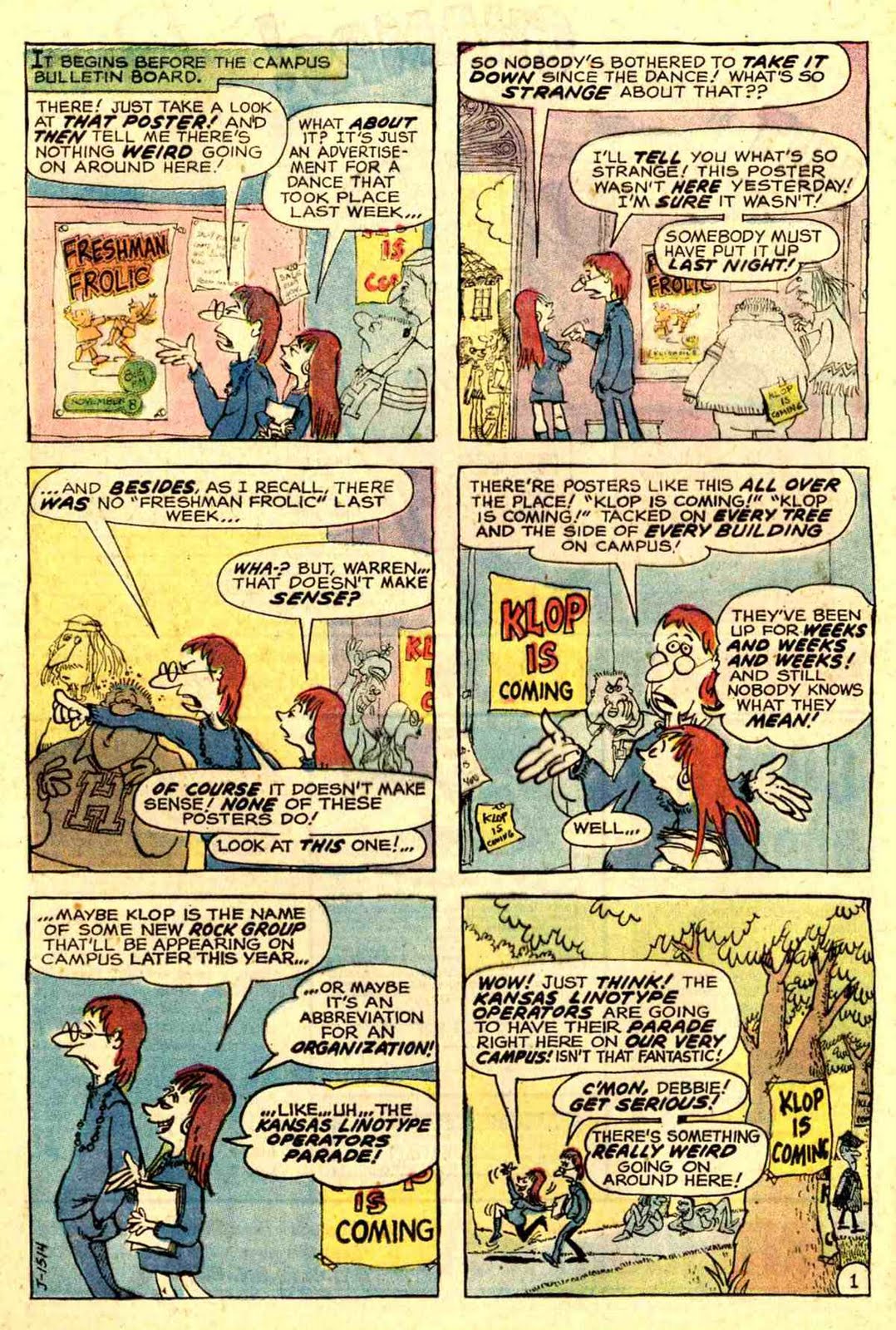

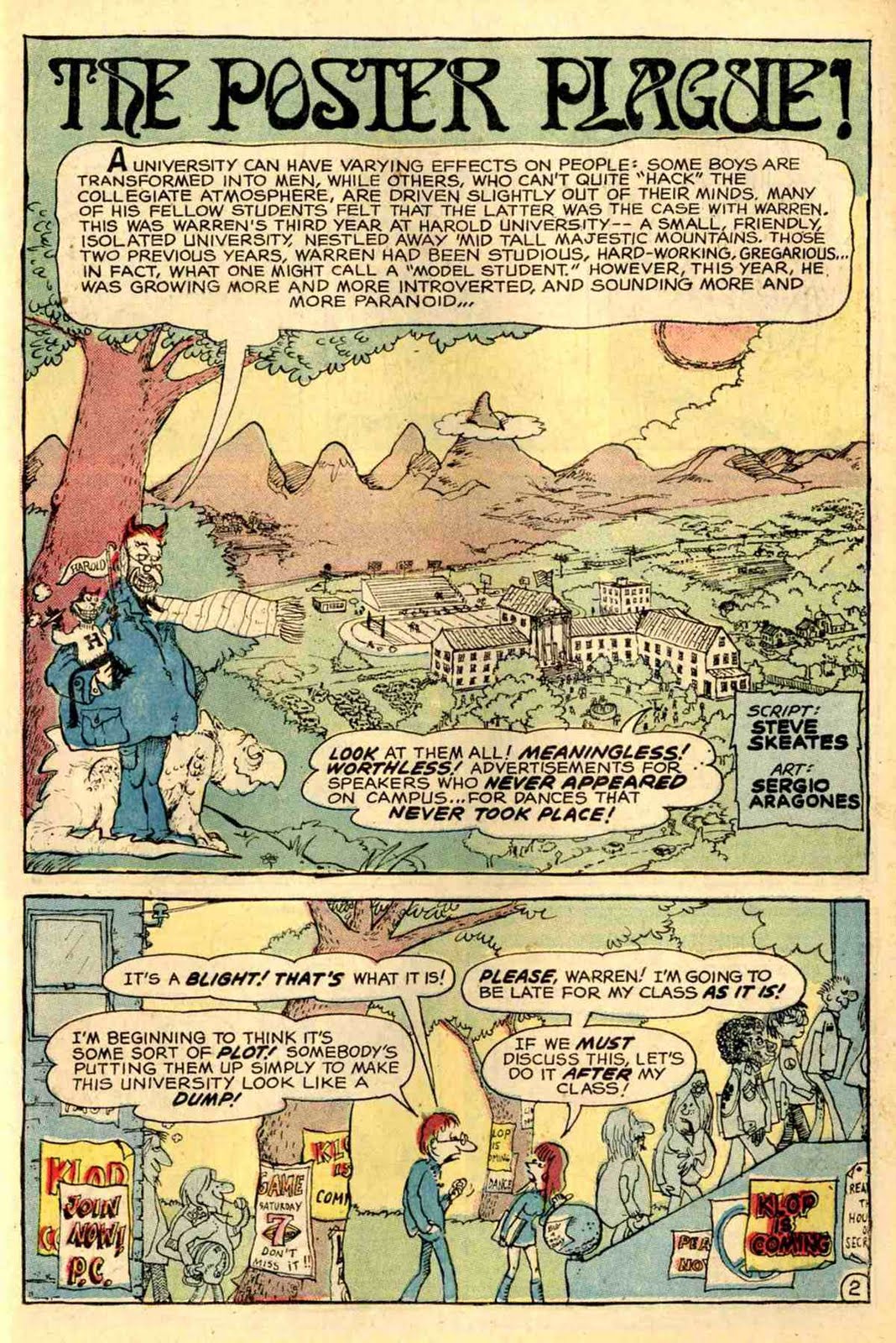

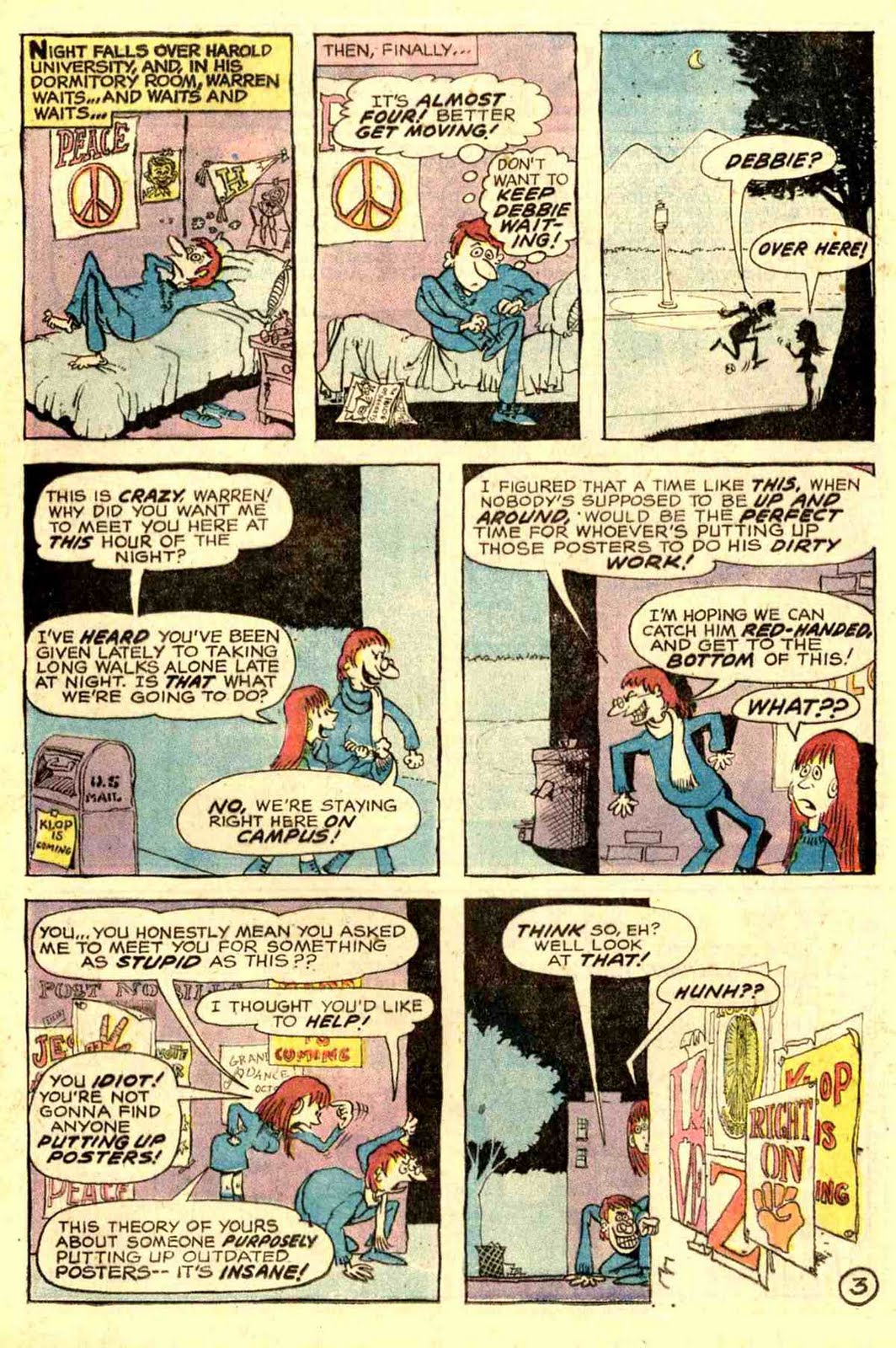

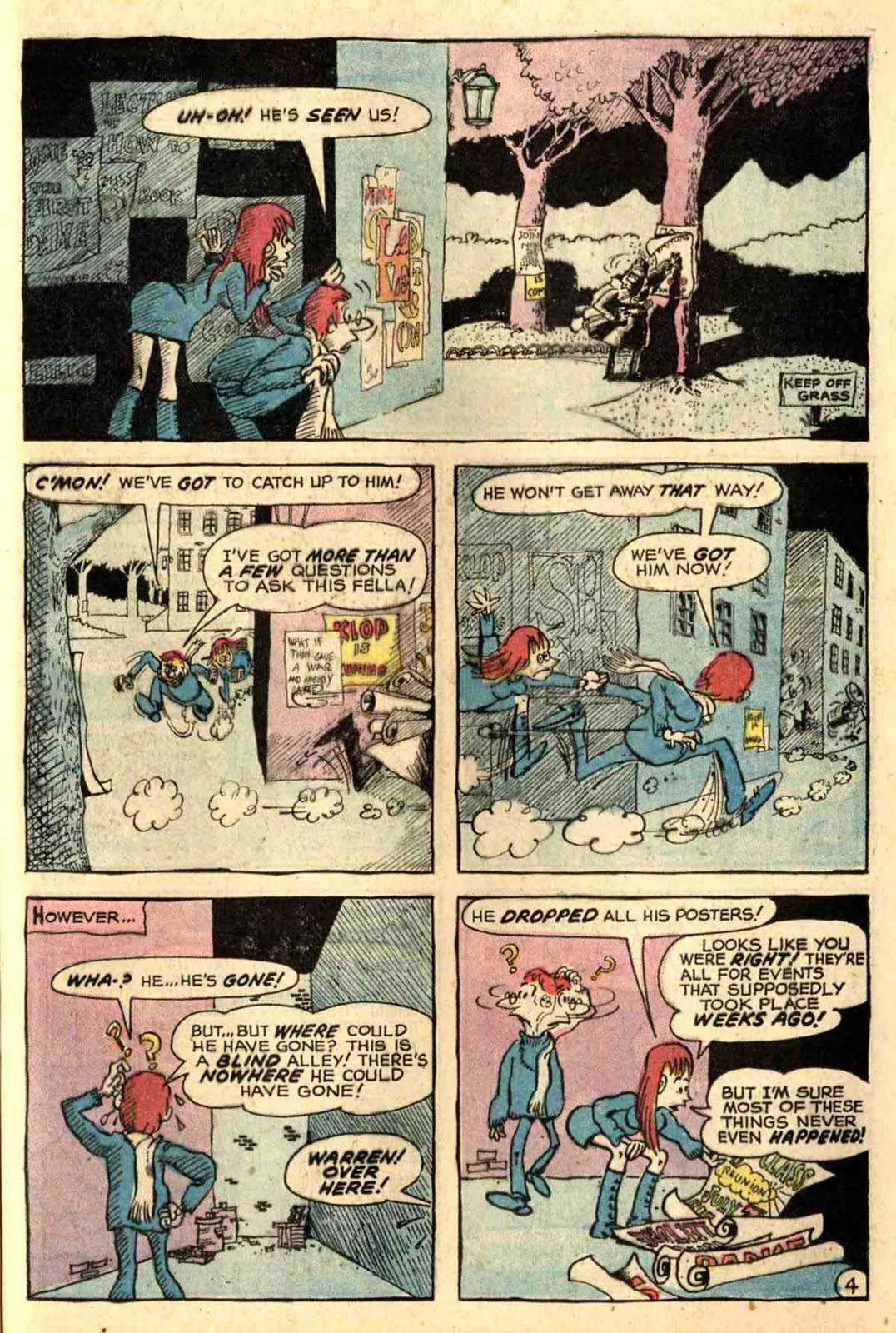

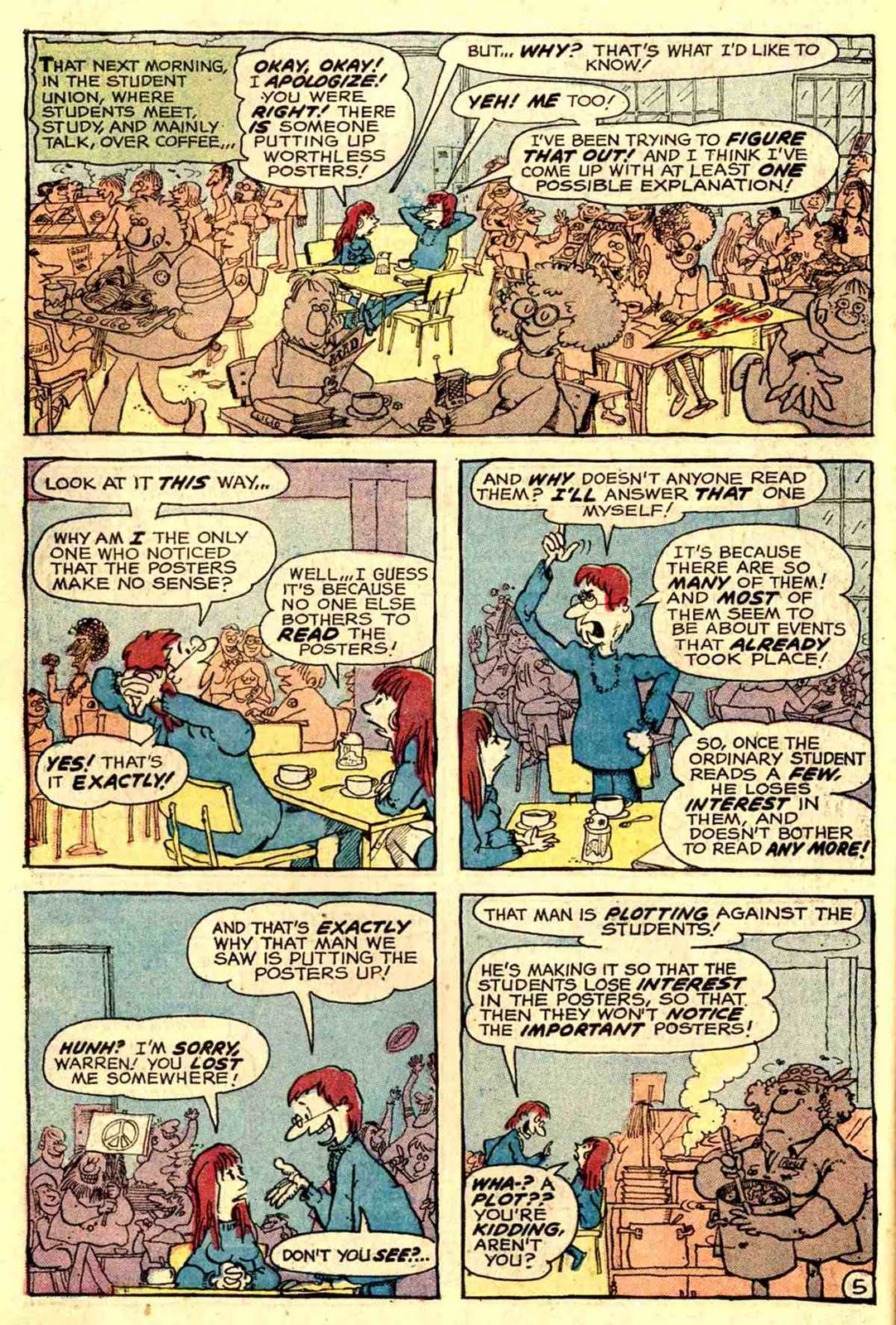

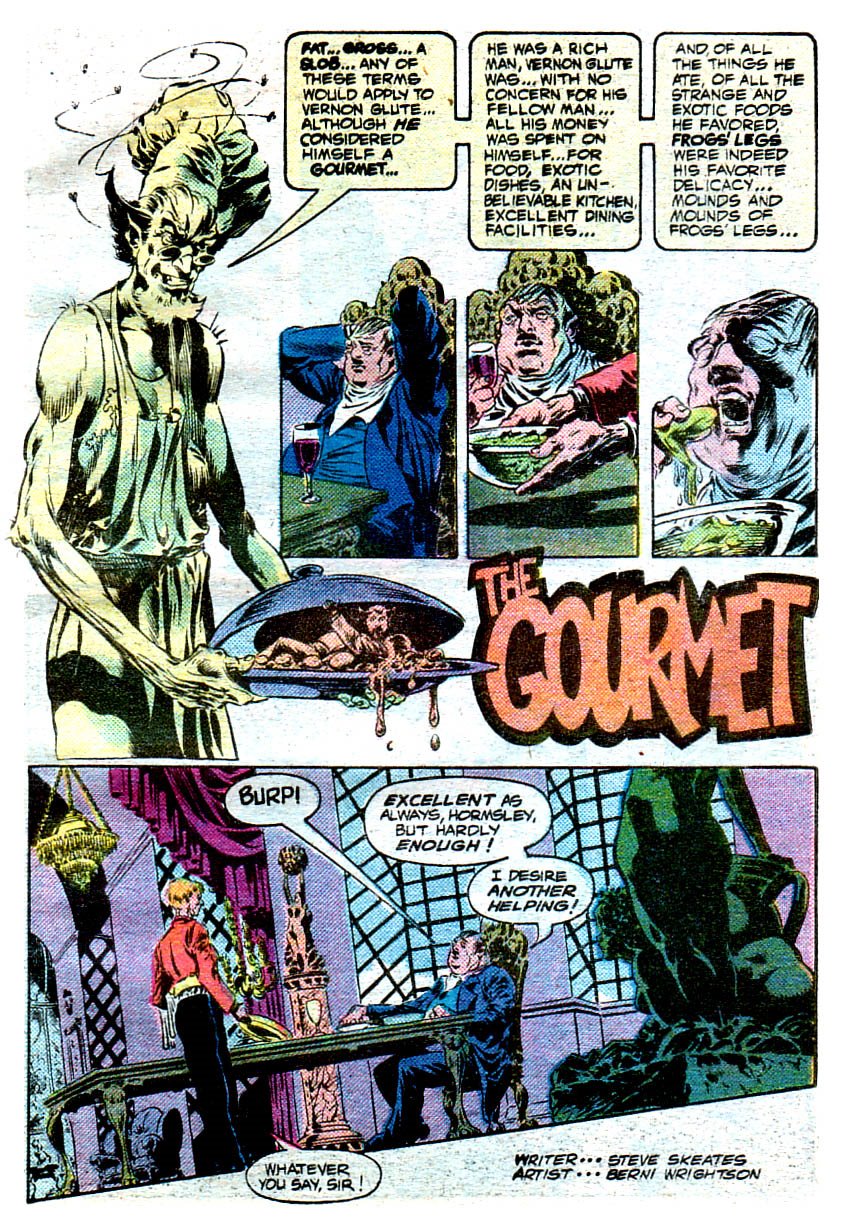

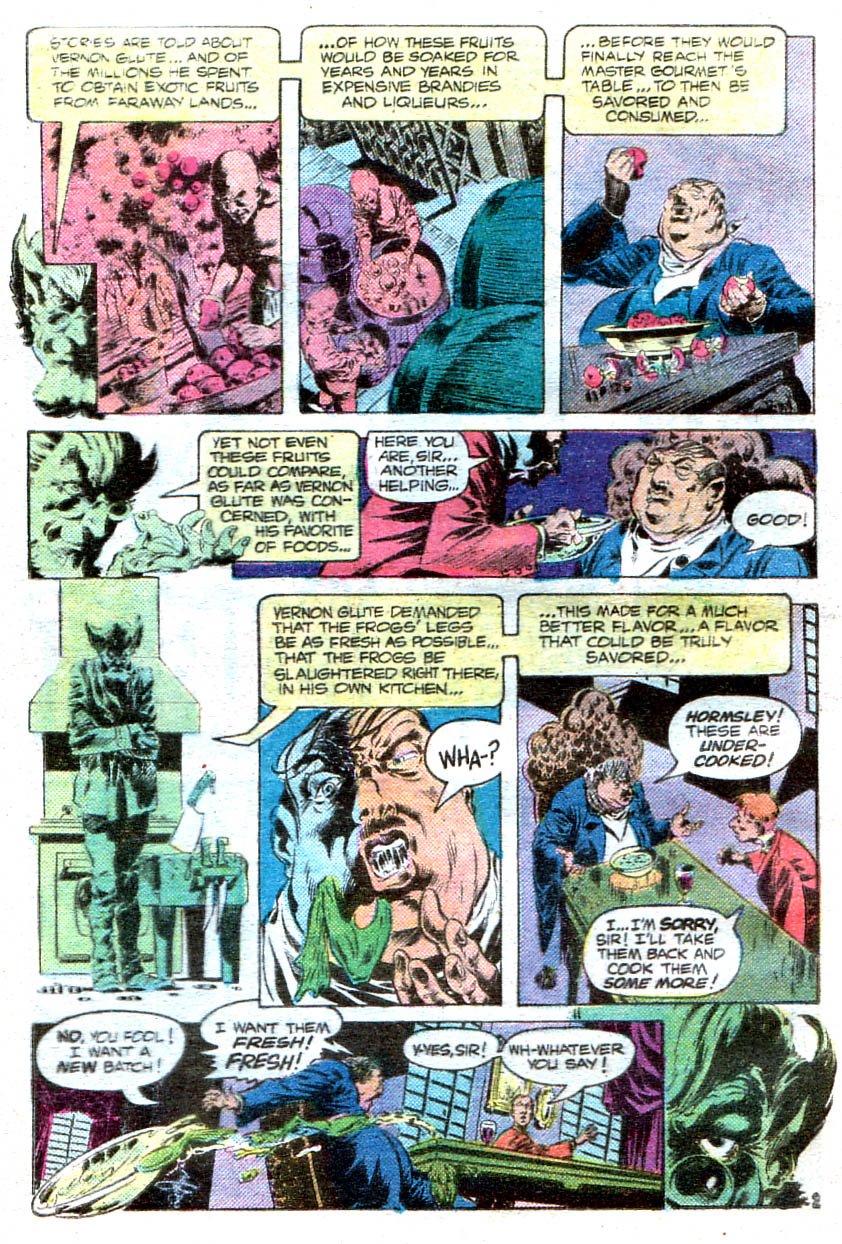

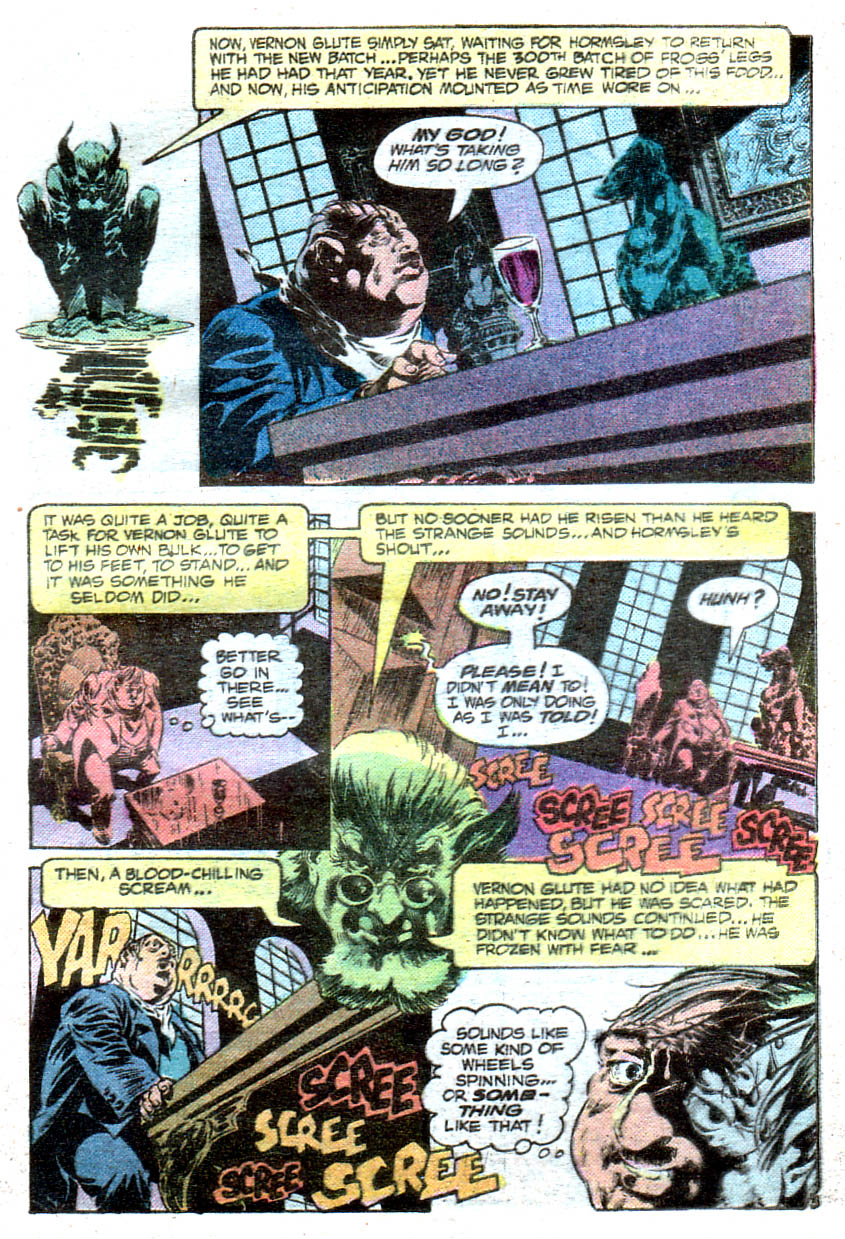

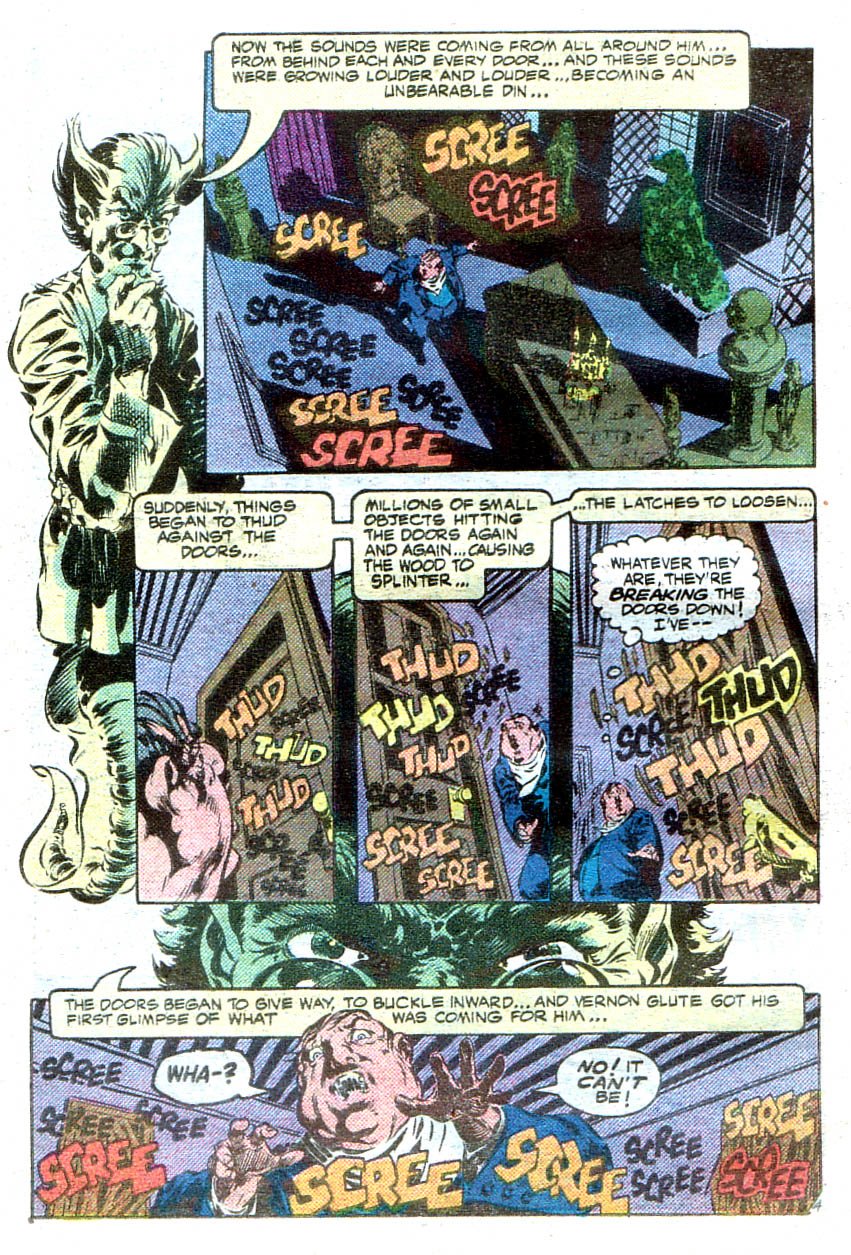

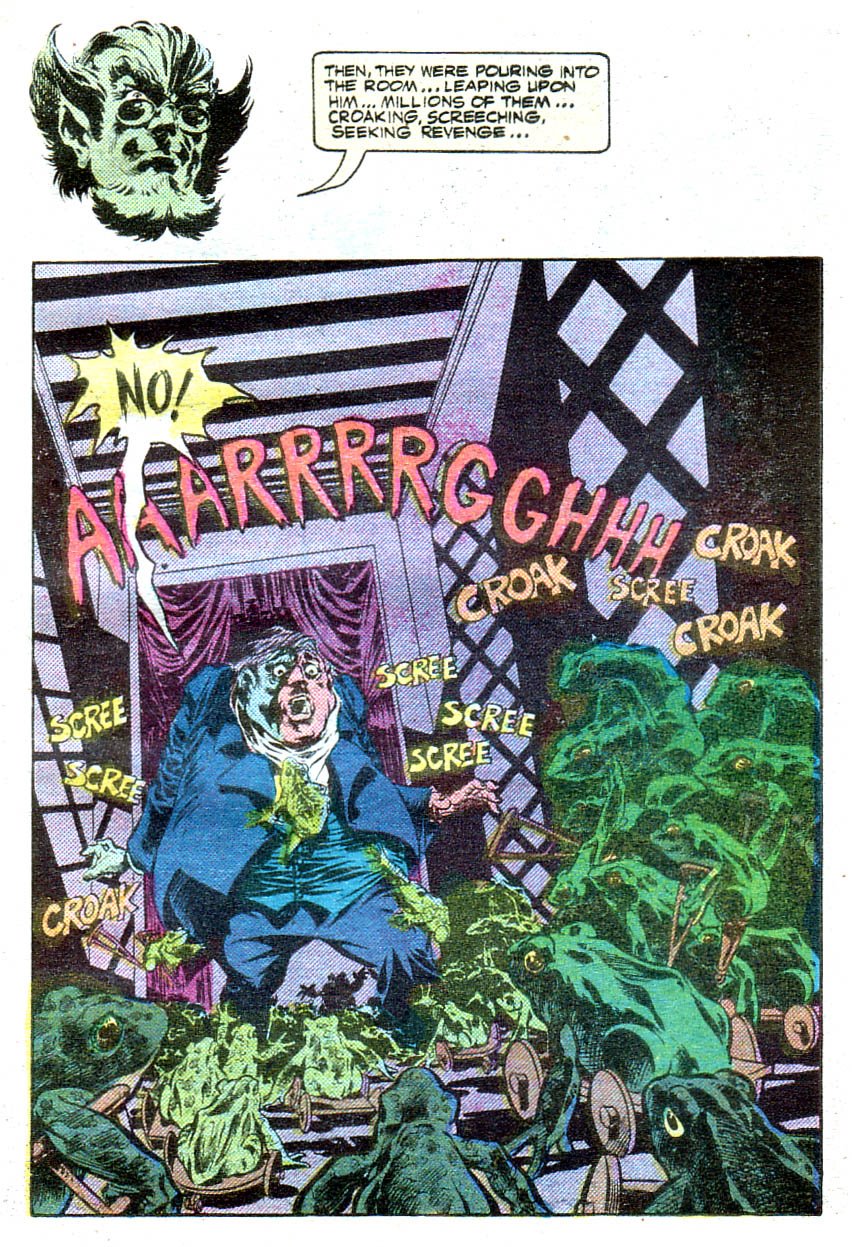

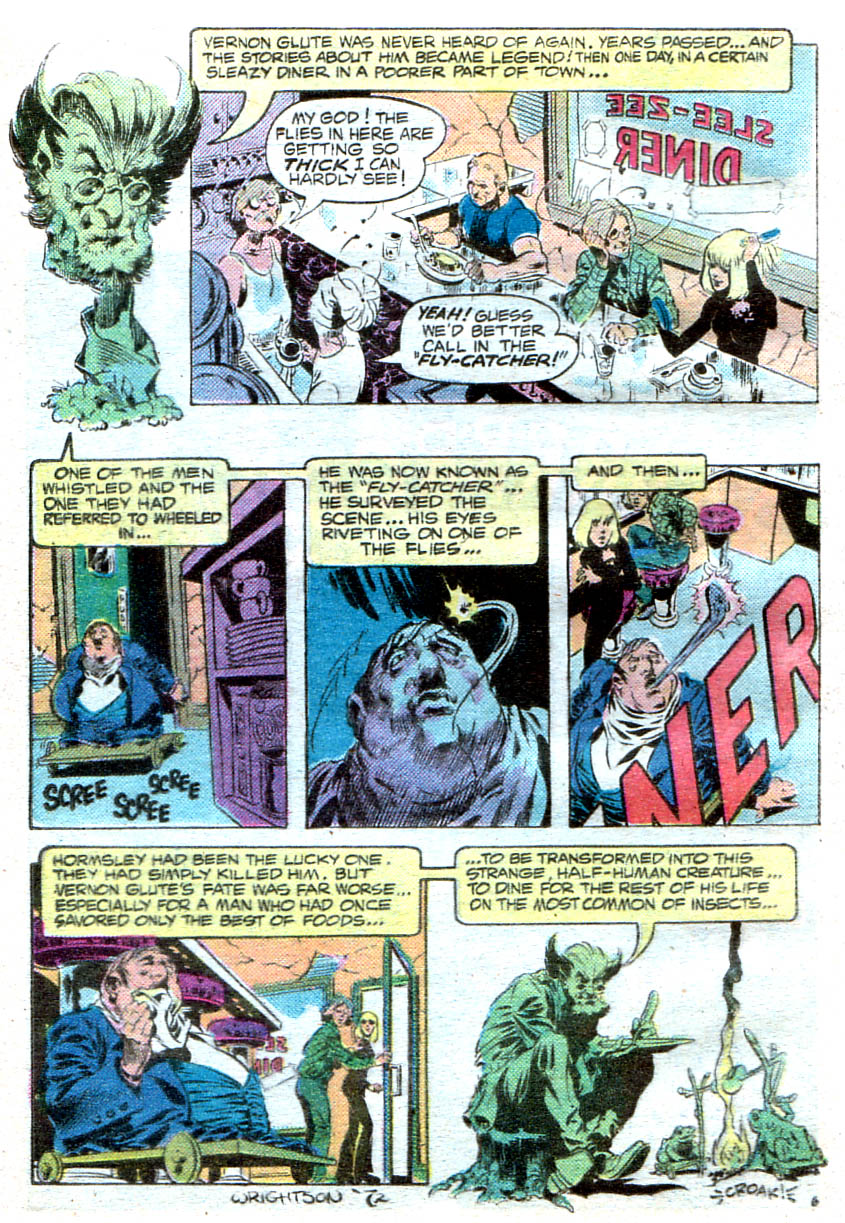

As an added bonus for our readers, here are the complete printed versions of "The Gourmet" and "The Poster Plague". Enjoy!

"The Gourmet" - Written by Steve Skeates with art from Bernie Wrightson.

"The Poster Plague" - Written by Steve Skeates with art from Sergio Aragones.